While the world is diligently practising self-isolation and social distancing during the global outbreak of covid-19, Islamic arts experts and aficionados are mourning the spring Islamic week. All the London auctions have been postponed until June with the hope that the pandemic will be gone by then, but in reality, there is no guarantee.

I am one the lucky few who can work from anywhere in the world, so my schedule during confinement has not changed much, only the size of my desk. For this reason, I have not be able to post more, nor to catch-up on my readings, but overall I am very grateful to be in this situation.

For the others who have more time on their hands that they know what to do with, I’ve just started a Resources page dedicated to Islamic arts. Hopefully, it will give you a solid base to occupy your days.

The content I publish is extremely niche and can be of little interest to those who aren’t familiar with Islamic Arts history. I’ve talked in other articles about some challenges linked to Islamic arts, especially what it is and how it is showed to the public, but I am yet to write about the very basis of Islamic Arts History in the West: collecting.

Through the diversity of the field, Islamic arts constitute a great object of curiosity and collection. Whether you focus on ceramic, painting, metalwork, textile or glass, and regardless of your budget, productions from Islamic lands represent a solid investment for buyers.

There are three branches on the Islamic art market, leading to different auctions and different pricing:

- Pre-modern: artefacts mostly produced before 1900 in Muslim lands, or more rarely in Europe for the Muslim market

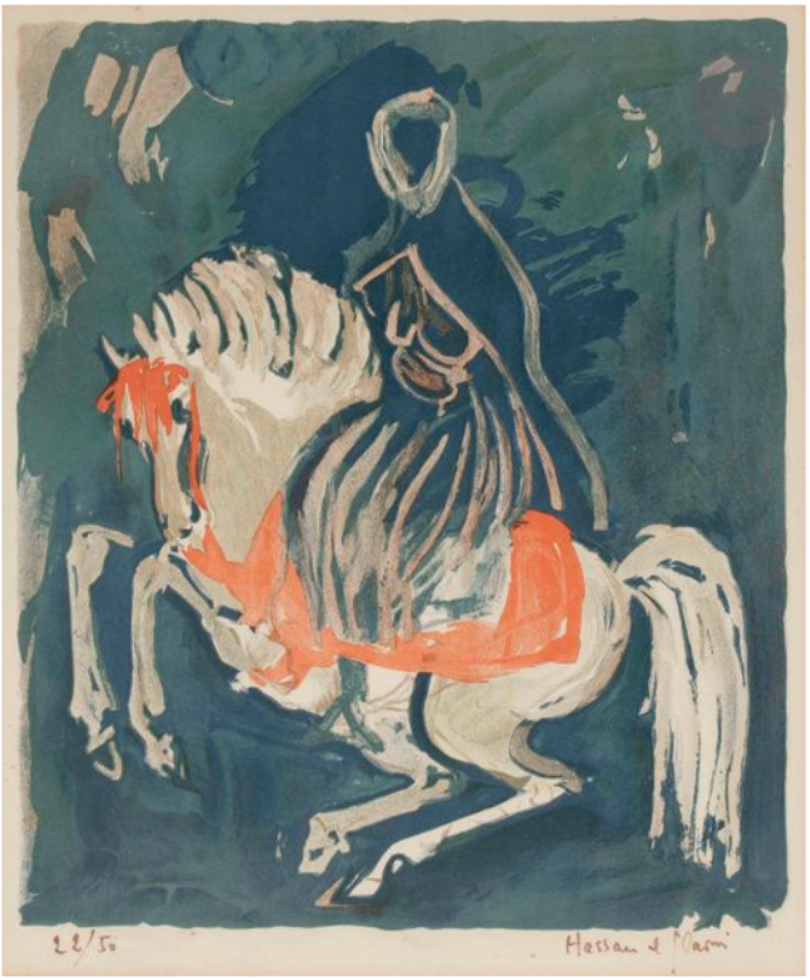

- Orientalist: mostly paintings and statuettes produced in Europe around the 1900’s (roughly)

- Modern and Contemporary: Islamic creation after the 1900, about which I write here.

In the present article, I will focus on the Pre-Modern category. In general, branches of Islamic arts are represented in dedicated auctions but some cross-overs are also possible, especially between Pre-Modern and Orientalist, or Orientalist and Contemporary.

Where to buy

In short, it all depends on your budget, even more than what you’re looking for. As a rule, better stay away from online auctions without real physical headquarters, as artefact provenance is not always documented, nor even guaranteed to be legal. Same goes with most independent sellers working on Facebook, Instagram or LinkedIn. Provenances are a big issue on the Islamic art market, especially after the years of war in the Middle-East, all the way to Pakistan1 and prudence is particularly needed for archaeological finds and architectural ceramic tiles, as they might come from illegal looting, destruction of archaeological sites (and complete loss of data for archaeologists and historians) and degradation of historical monument, not to mention probable exploitation of human lives. This is not a matter to take lightly. Luckily, the auction houses and galleries mentioned below take every precautions with researching and documenting lot provenance and are therefore safe to turn to.2

The main cities where to buy Pre-Modern Islamic arts are London and Paris. In London, Sotheby’s and Christie’s condense the most prestigious lots in two auctions per year, in the spring and the fall. Valuations are the highest of the market and though are sometimes difficult to justify compared to Paris, they usually come with the best preserved, most beautiful artefacts.

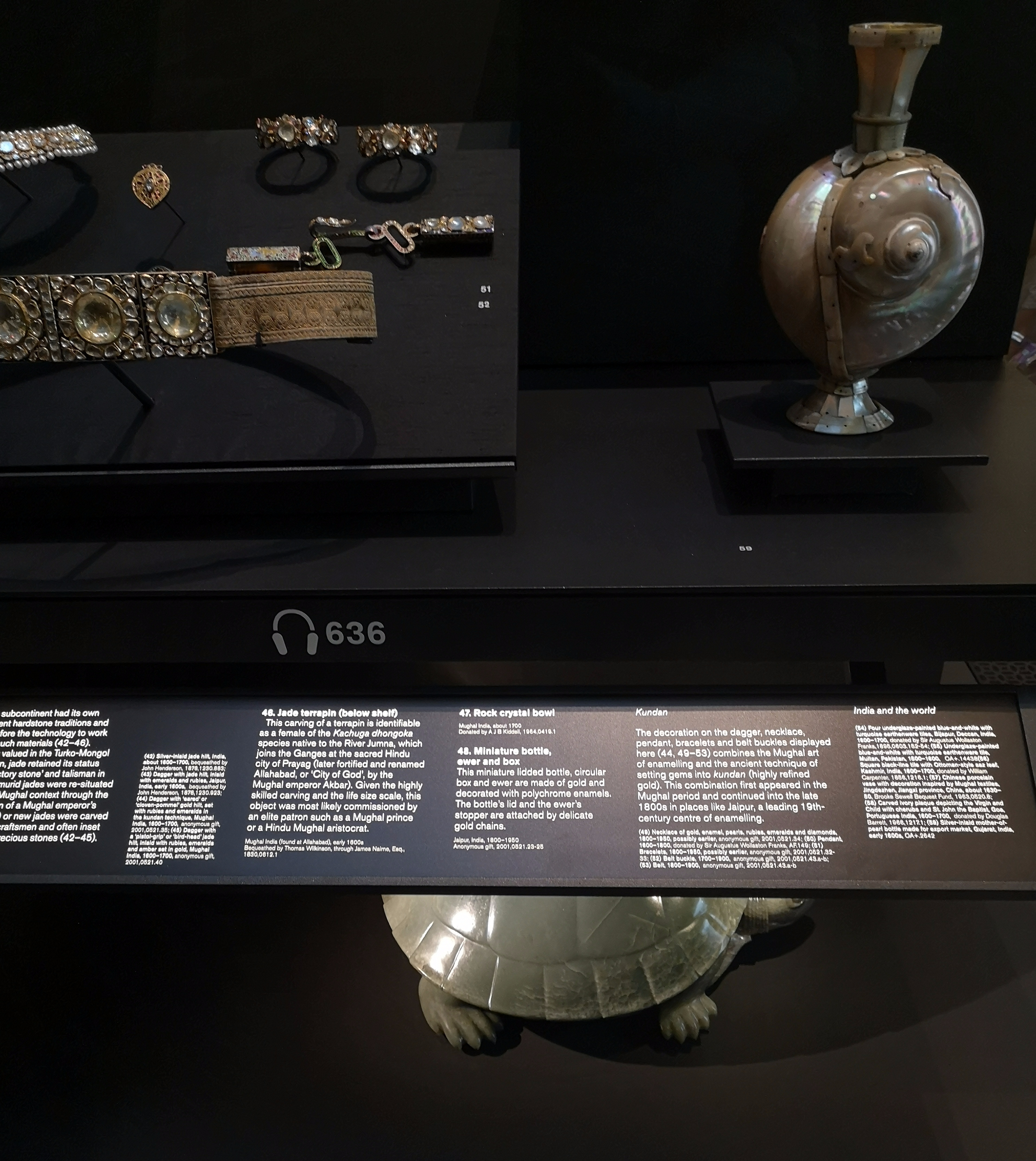

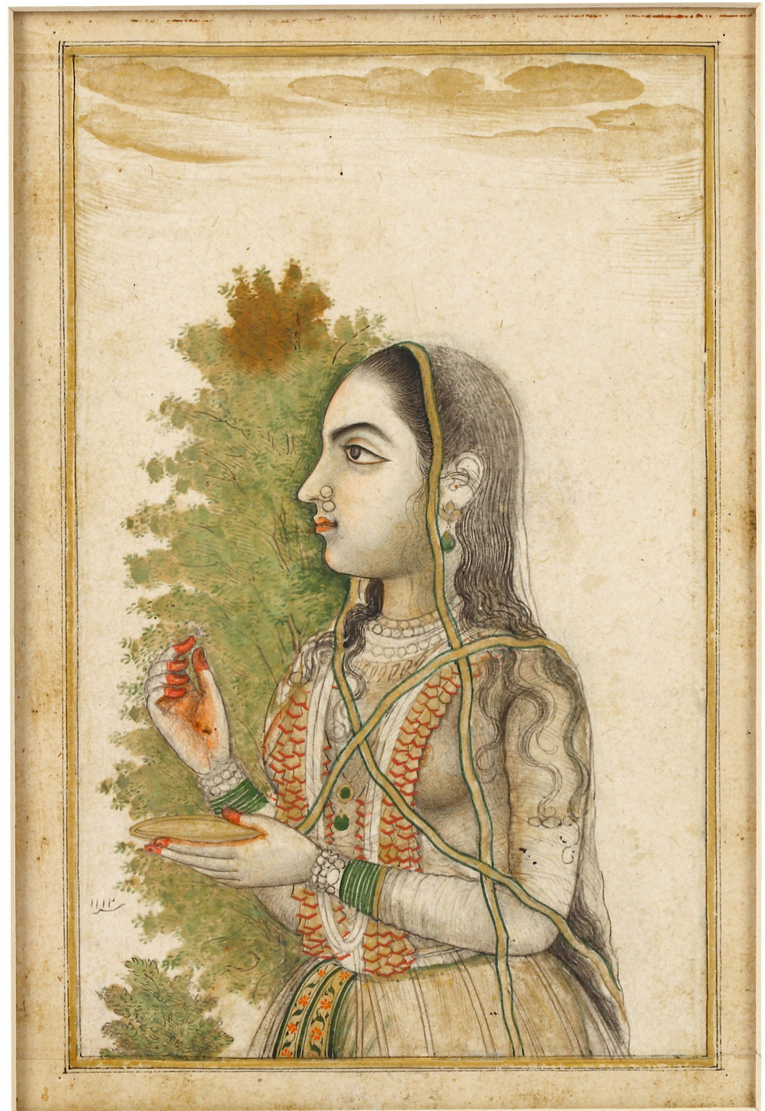

Bonhams constitutes the second level of the London market and offer a less expensive selection, more and more focused on Pre-modern (16th-19th centuries) Indian objects.

Finally, Chiswick auction represents a very good entry point for new collectors with a smaller budget, as well as Roseberys that organises auctions with a chronology spanning from millenniums B.C. to the present day, and Bloomsburry who entirely focuses on manuscripts and paintings.3

A large number of galleries are also installed in London, such as Simon Ray (Indian & Islamic arts), Francesca Galloway (Asian & Islamic art) David Aaron (Antiques & early Islamic). Prices in galleries are usually higher and subject to negotiations, and if you start following the market, you will sometimes see pieces sold in auctions offered in galleries some time after. Other pieces are previously unseen, though there are becoming increasingly rare in a market that is working mostly in close loop.

In Paris, prices are lower, though it doesn’t necessarily mean that the items are less interesting. The main auction houses to follow are Millon & Associés and Ader Nordmann, which organise two auctions per year following the London Islamic week. Millon also organises secondary auctions shortly after their mains, with items of lower value, but still of aesthetic significance.

Sotheby’s Paris use to organise Orientalist auctions but hasn’t done so in 5 years.

Boisgirard-Antonini also organises one to two auctions a year, while other houses like Gros & Delettrez, Rossini and Leclere focus on Orientalists. Finally, it is worth looking at Binoche & Giquello that sometimes offers secondary Islamic items for very low prices, usually in generalist auctions (but you really need to have your eyes wide open, these auctions are rarely advertised outside of Drouot).

Galleries Kevorkian, Samarcande and Alexis Renard are the main three you need to look at, with a special mention to the latter for the reflection initiated around art displays and the relation to art, through “sensory” guided tours.

In New York, Christie’s sometimes organise exceptional auctions, such as Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence in June 2019, offering part of the Al-Thani collection, but this is quite rare.

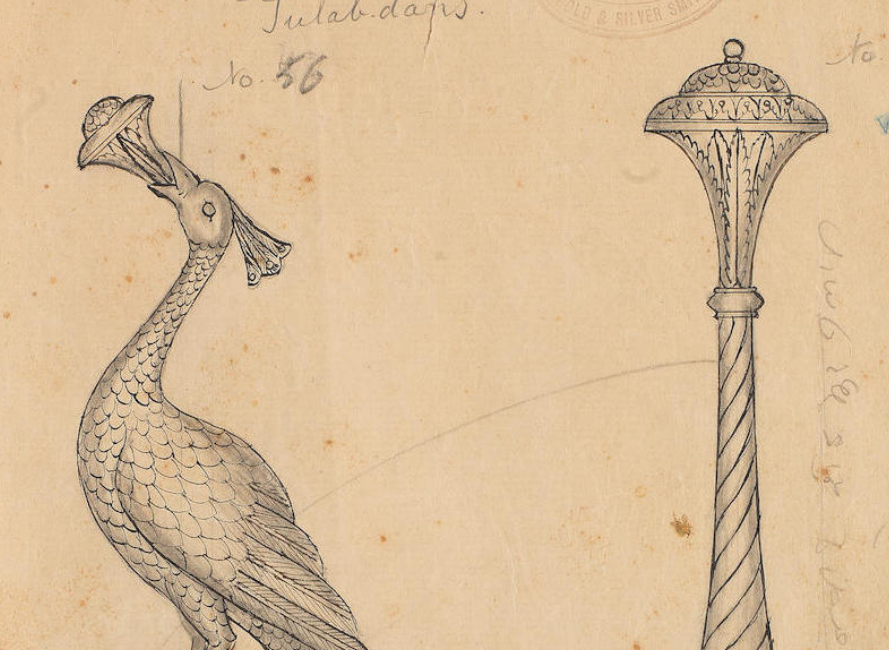

To my knowledge, Carlton Rochell is the only noticeable New York gallery to offer Islamic art. They specialise in Indian art and have a very nice selection of paintings.

How to buy

All these references can already be overwhelming for a new collector, but all the auction and gallery catalogues are put online with high definition pictures, so it is very easy to sit in front of your computer an evening or on a lazy Sunday and browse websites for an initial selection. Galleries usually publish one catalogue per year and there is no set date on which you can buy. London auctions are usually held twice a year during the Islamic week, roughly around April and October (for normal years, not 2020), so looking in July is usually futile.

I would not advice buying solely on photos, especially for pricey items, as pictures can be deceiving. I’ve done it without regret so far with trusted sellers, though I ended up, not long ago, with a very nice late Ottoman ewer and basin a lot bigger than expected. To this day, I’m still looking for the best place to display it.

Beside surprises (amusing or far less), having the feel of an object, being able to touch and hold it, might completely change your opinion on it, so going to auction houses during exhibitions is always a good idea. This can feel quite intimidating but try to go past it and don’t hesitate to ask to see each piece you are interested in from a close, even have paintings removed from their frame to see the back. In the end, it depends if you buy to keep or buy to invest. In both case, make sure the item meets your expectations.

In any case, always request the “condition report”, which gives more information than the catalogue entry on the actual preservation state of an item.

Gallery prices are not announced on catalogues and you will need to contact them directly to get an estimate.

Auction catalogues show two prices on each lot, a “low estimate” and a “high estimate”. Usually the low estimate is close to the seller’s “reserve price” (meaning the minimum price the seller will accept) and a bid can start below that price. When you bid on a lot, always remember that the final number, called “hammer price”, is not what you will pay, as auction houses remunerate themselves by adding a premium on top of the hammer price, usually around 25% to 30%. Remember to read the house terms and conditions prior to put a bid to know exactly how much premium you’ll have to pay.

The same way, if you wish to sell in auction, you will need to pay a “seller’s commission”, usually around 10% of the hammer price, to cover for valuation services, photography etc.

To bid on a lot, you will need to register with the auctioneer and provide your personal and bank details. You will be given an unique identifier that will allow you to bid anonymously in a given bidding room (with the little sign you’ve seen in movies), or to bid online if you cannot or do not wish to attend. Note that the “bid increment”, the amount by which the auctioneer increases the bidding, is not yours to chose but is usually located around 10% higher than the previous bid. For instance, if the bidding opens at £5.000, subsequent bids of £5.500, £6.000, £6.500, etc. would follow. The figure is generally rounded up or down at the auctioneer’s discretion.

After the auction, an invoice will be sent to you with a deadline to pay, and you will then be able to retrieve your purchase. Most auction houses assist with collection and delivery but you will have to pay for the service, so don’t forget to count this in your budget.4

What to look for

This part is the most complex part, as Islamic arts are so diversified. Going through all the productions would take far too long for an article titled “short”, but instead, I will leave you with some tips.

Why are you collecting?

This is an important question, as the answer will profoundly impact your biding activity. If you are looking for a long term financial investment, and are ultimately buying to sell, you will need to study the market trends. This is not necessarily an easy thing to do, and going for the most expensive items might not be the answer. Trends evolve relatively fast, given than most of the market activity is condense over two weeks per year, and to understand them, it is often necessary to go back over a long period of time.

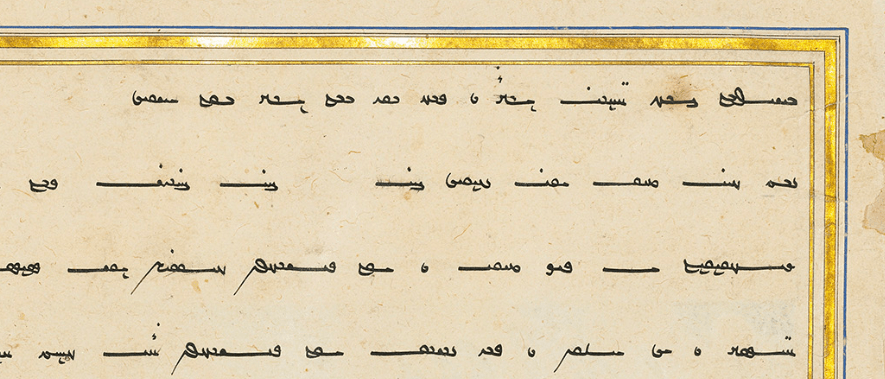

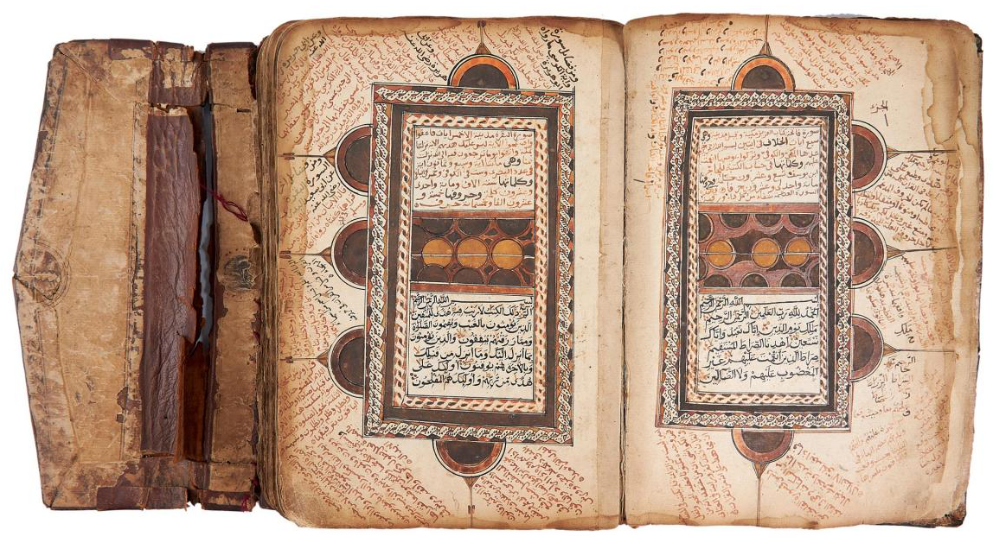

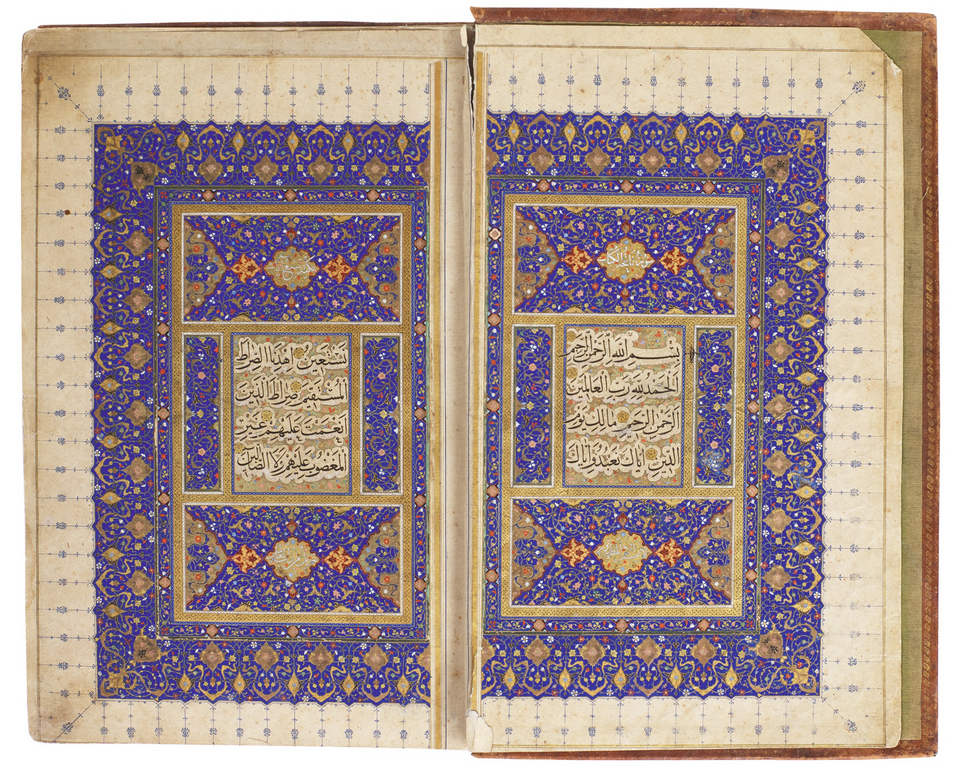

For instance, Sotheby’s will present a 9th century Qur’an leaf in Kufic script on the 10th June for £60.000-80.000. Ten years ago, a very similar page from the same manuscript was offered by Sotheby’s Doha for £91.5000-£126.700.5 During the course of the last eleven years, this type of production has lost in value, so selling now might not be the best.

On the opposite, both Sotheby’s and Christie’s will be presenting Medieval Persian potteries from 13th century Kashan (a famous production centre in Iran), a production that had not been properly represented on the market for a while. These pieces are expected to reach high prices, and more collectors might want to sell their Kashan ceramic pieces after that, resulting in a new trend and an increase of prices. Time will tell.

If you buy only for your own pleasure, you still need to look at trends to make sure you get the best deal on the item of your choice. It might be the right time to get 9th-10th century Qur’an pages on vellum, same with late Kashmiri Qur’an that are not particularly in favour at the minute. As well, don’t only monitor the London market (and not only Christie’s and Sotheby’s obviously), but keep an eye out for Paris market, on which prices are naturally lower but quality is not. In the end, you are in a great position, as you are only limited by your budget.

An important piece of advise: you need a set budget before starting to bid, as well as strong discipline to make sure you don’t go over. Biding on an item you love is an exciting experience that triggers a dangerous sense of commitment. Don’t go crazy, if you don’t get this particular item, another will come at a later date.

Think about conservation

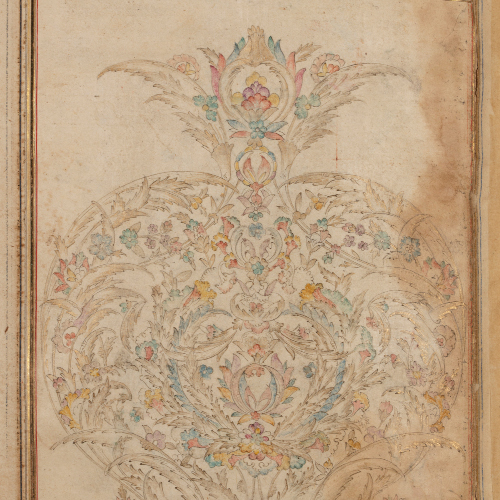

If you own a private safe somewhere in Switzerland, this section doesn’t concern you. For the rest of us, how to preserve and display art is an important topic. Indeed, art is fragile, and the last thing you want is your cat knocking down your recently purchased 17th century Safavid blue & white pottery ewer elegantly displayed over the fireplace.

Before you buy anything, it is important to think about what you are going to do with it. I was joking earlier about my late Ottoman ewer and basin that are too big for my living room, but I was actually lucky I could place them on top of a bookshelf where they are safe. The same way, I collect metalwork, even though my first love is with manuscripts and paintings, because it is easier to store and preserve. If you decide to buy a single page painting, for instance, you will need a frame with UV protecting glass, which represents an additional cost, or display it on a wall that has no direct sun exposure and either provide additional non damaging lighting or accept the fact that your painting will be in the dark forever. Same go with textiles, that will need to be dusted, cleaned and treated and very specific ways, or even manuscripts that need moist control, light control and parasite control.

Don’t feel discouraged by all these constraints but keep them in mind prior to biding and plan accordingly. There is no better feeling that preparing a space for a newly acquired addition to your personal collection.

These are just a few insights into collecting, and there is a lot more to write about starting a collection of Islamic arts. In the future, I will get in more details about specific productions well represented on the market. If yo have any questions, article suggestions, or want to start your own art collection, I’ll be happy to provide support, feel free to get in touch.

- See my article published in IWA Mag in Winter 2019.

- All the links are on the Resources page.

- Part of Dreweatts.

- For all the technical terms, you can refer to Sotheby’s glossary.

- The exact valuation was $130.000-$180.000.