This January, for the first time in three years, I was able to fly back to Paris. I lived in the city for nine years before moving to the UK, so coming back is always a moment I treasure. I get to see old friends, walk through the lane of my 20’s memories, and catch up on current affair, namely, this time, getting to the Musee des Arts Decoratifs to see the exhibition Cartier et les Arts de l’Islam.

I initially intended to do an Instagram live through the exhibition but I had too many conflicting feelings about its content, and promptly decided to write them down in a more structured fashion.

Two remarks between jumping in: First, I only saw the exhibition and haven’t read the catalogue (hard-cover sold for 62€ in the museum store, I almost chocked), so my opinion is solely based on the exhibition rooms. Secondly, the pictures below have not been edited or altered in any way. The reader will excuse the absence of information on the objects depicted such as accession numbers, my intend here is merely to give an opinion, not redraw the exhibition.

The fine line between intimate and hazardous

Two years ago, I wrote on this blog an article about the way Islamic arts are displayed in museums, with a section titled “The literal darkness of Islamic arts” in which I was questioning the common choice to install displays in particularly dark rooms. The Louvre and the British Museum, with their newly refurbished Islamic arts departments, are particularly relevant examples of this trend.

The Cartier exhibition follows the fashion, but takes it a step further by plunging the rooms in pitch black, to the point where I saw people bump into each other.

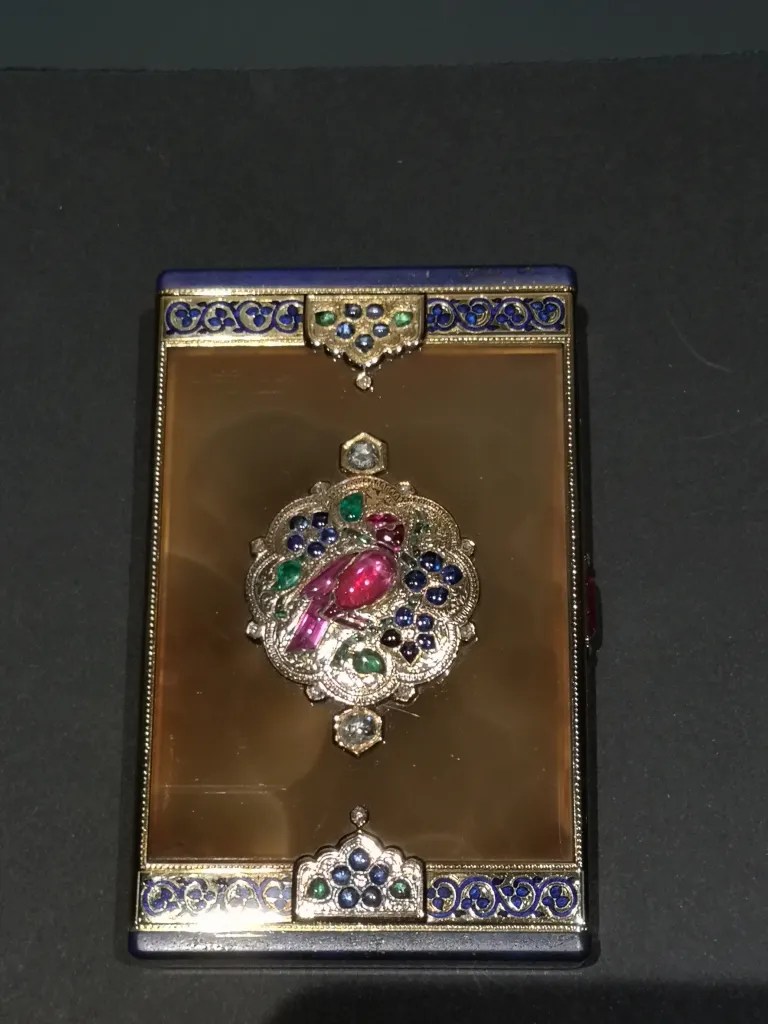

The benefit of such a display is the contrast with the exposed pieces, in particular the jewellery that was very cleverly lighted. Now, I am not particularly familiar with jewellery exhibitions, and maybe this kind of “non-lighting lighting” is common practice, but I struggle to understand this trend with Islamic art display. It seems to me that Islamic arts are purposely kept into dark rooms to signify a sort of mystery, somehow linked to the notion of Orient as seen by 19th century orientalists, fascinated by harems forbidden to men, and palace intrigues hidden behind musharabieh. Delicate Persian paintings and princely cups made of semi-previous stone were, after all, not intended to be seen by a large public, and current trends might be trying to emulate that idea of privacy. My interpretation might completely be off, it might just be a particularly annoying museography trend that will eventually be replaced by another, I just cannot help but wonder.

A point not completely made

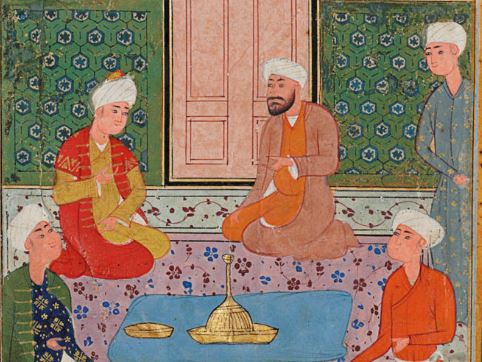

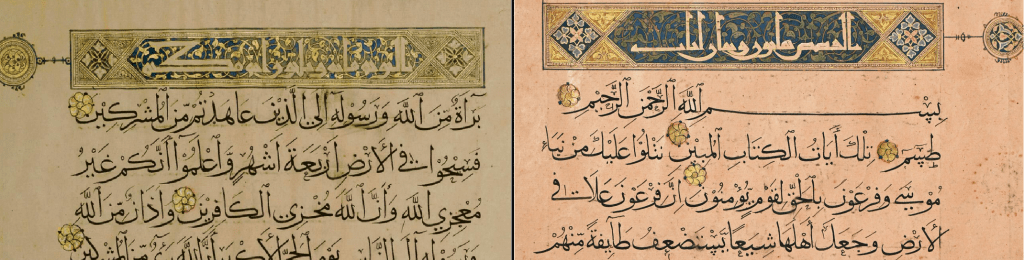

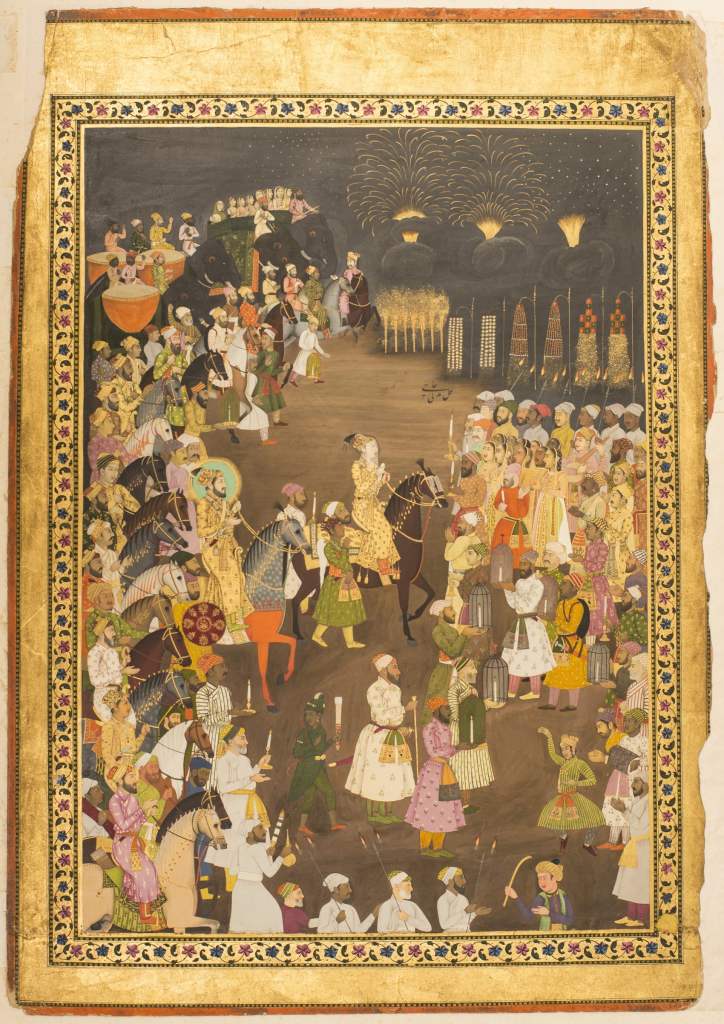

The ambition of the exhibition is to show the close connection between the Maison Cartier and Islamic arts. For this, it is divided in two halves. The first one treats of different thematics, for instance the Persian taste in French decorative arts at the end of the 19th century, the diffusion of non-European decorative patterns through ornament books such as The Grammar of Ornament of Owen Jones, etc. The second half of the exhibition is more centred on iconography, juxtaposing Islamic or Indian artefacts bearing particular patterns (such as botteh, mandorla, cintamani etc.), with Cartier pieces ornamented with the same patterns.

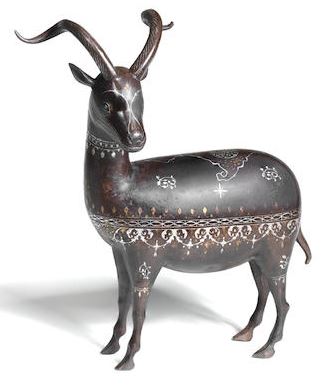

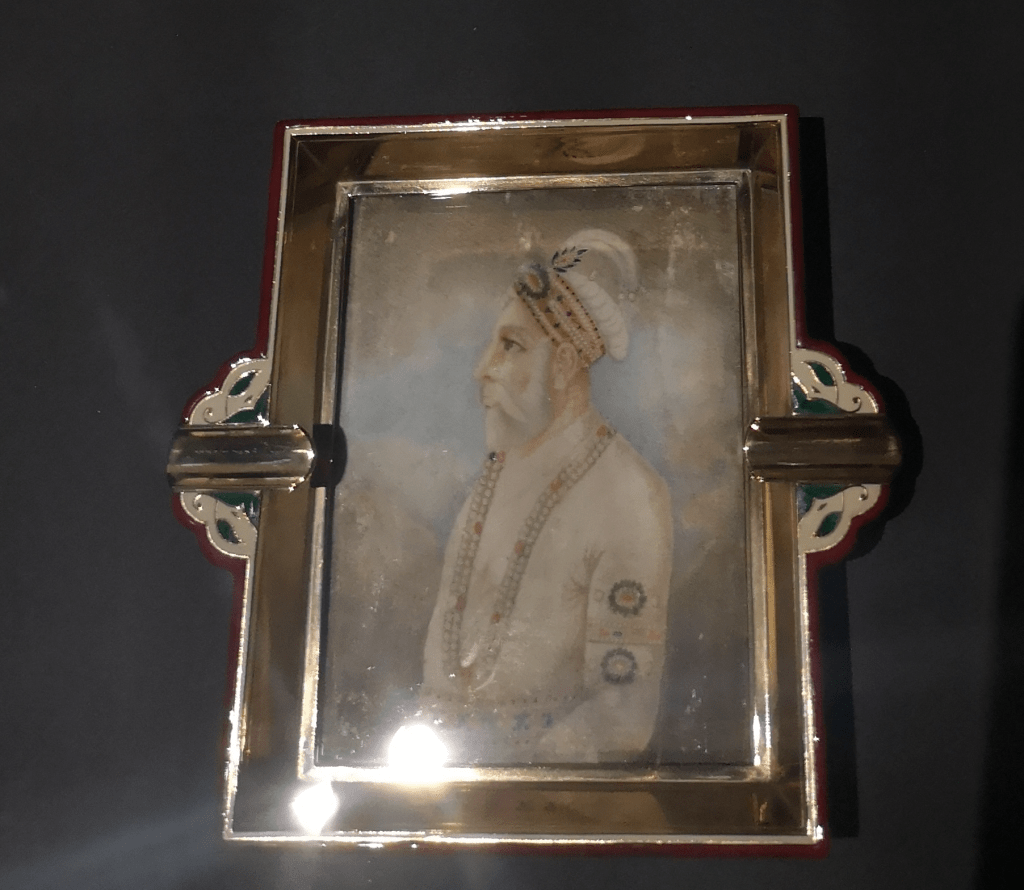

In the first place, it is important to note the disproportion of Cartier jewels and Islamic pieces. I fully appreciate the fact that this is a Cartier exhibition, with many pieces coming from the private Cartier collection, but I do believe more Islamic pieces would have brought more clarity. Showing only one Mamluk wood panel carved with 8 pointed stars seems like a missed opportunity. Some choices also seem odd, though commendable, mainly for the lack of justification, which left the visitor to read between the line. For instance, the life-size portrait of Fath ‘Ali Shah Qajar, Iran’s ruler from 1797 to 1834, has been landed by the Louvre for this exhibition. The painting is installed between the tiara-aigrette reproduced above and a pearl necklace. Neither piece appear on Fath ‘Ali Shah’s portrait, which was produced almost a century earlier than the two jewels, so what is the point made, beside showing that the ruler was dripping in pearls? Another example is the first room of the exhibition, titled “A Persian taste”, in which the very first object is a Mamluk glass lamp.

Here lies my main issue with the exhibition: the absence of nuance. The entire display seemed like a juxtaposition of pieces that share common patterns. This is fair, the ambition is clearly stated in the title, however it would have been beneficial to push the analysis further. The “Islamic” patterns presented to the viewers are just there, with no explanation on where they come from, how they were developed, what is their function and what is their meaning. All these motives are transposed to Cartier jewels without much critical analysis. The first two or three rooms attempt to contextualise the passion of aristocratic Europe for Islamic arts and the taxonomical effort of ornamentalists and travellers, but it remains unclear what those ornament books are used for, beside for Cartier creations, and what is the real impact on the knowledge of Islamic arts and cultures in Europe. The beginning of the 20th century is an important moment in Islamic arts history in Europe, which the exhibition recognises by mentioning Gaston Migeon, but the explanations are not sufficient for a non-specialist to really connect the dot. They will have to buy the catalogue to understand.

What have I learned?

At the end of each exhibition, I always ask myself this question: what have I learned that I didn’t know before? In other words, what was the point of the exhibition? With Cartier et les arts de l’Islam, I learned about the history of the maison Cartier that I didn’t know, and I learned that between the end of the 19th century and the 1940’s, the house created luxury items inspired by or copied from Islamic arts. One could say mission accomplished, but I can’t help feeling like something is missing, and I remember leaving with a slight feeling of frustration. Maybe was it the overall darkness, the too minimalistic display for the main part, or the confusing museography, or maybe am I just tired to see Islamic arts presented like a block of objects out of time and out of space, mixing together Timurid architectural tiles and Mughal paintings, minbar carved panels and Iznik beer-mugs. Cartier used bits of Islamic arts indifferently, and this is how Islamic arts are presented in the exhibition, interchangeable, anonymous and confusing.

In conclusion, the exhibition treats Islamic arts exactly like Cartier did: a collection of pretty things that can be extracted from history and reused to make more pretty things.