With Summer fast approaching, I thought it would be the perfect time for some light reading to enjoy wherever you’re vacationing, and nothing get lighter than a list of top historical artefacts sold for outrageous amounts.

Three caveats before starting:

- I decided to divide this top 20 in two, it was too long otherwise;

- The list only goes back to 2010, mainly for access ease, but also because prices have exploded in the past few years and going back further is not necessarily relevant;

- I purposefully left the auction “Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence” out of this list, otherwise most of it would have been composed of objects sold there, and some being debatable as their “Islamic” categorisation. For those who wouldn’t remember, this auction was held at Christie’s New York in June 2019 and was composed of jewelled pieces, gems and paintings from the Al-Thani collection. The most expensive lot, a Cartier devant-de-corsage brooch, was sold for $10,603,500, which would put it in second place of the list after conversion. I wrote about the results of this auction back in the days.

As mentioned, the reader will quickly notice the dates of the record auctions: most of them occurred between the end of 2018 and 2023. This truly shows how London market has drastically changed in the past few years, with prices increasing rapidly. As Dr Hiba Abid was telling in the episode of the ART Informant podcast, this is an issue for institutions that cannot rely on London’s market to expand their collection. However, this is a question for another day, as we are keeping the content light, so let’s jump into the first part Top20! In true internet fashion, we’ll start with the last.

All prices include premium. Click on the auction date and estimate to access the catalogue notice.

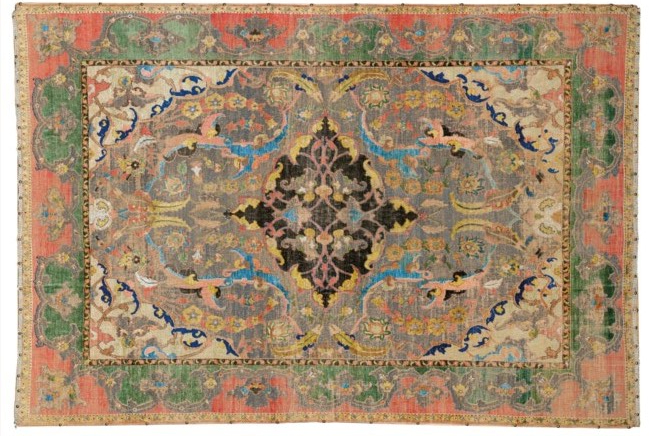

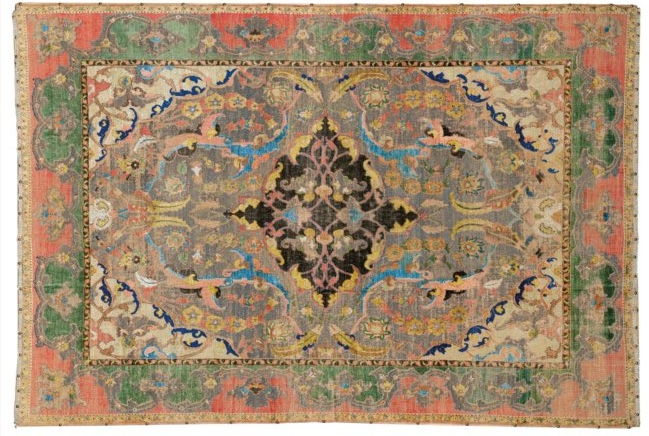

20 – £1,854,200: A Mamluk Carpet, probably Cairo, end of 15th c./ early 16th c.

Sotheby’s, 27 October 2020, lot 448: £400,000 – 600,000

This list starts with a very rare piece on the art market. Probably made in Egypt in a production context that remains to be precisely defined, these carpets were widely popular in 15th and 16th centuries European markets, especially around the Mediterranean sea where several were found in ports such as Venice and Genoa. In 2018, the blog “rugtracker” posted an in-depth article on Mamluk carpets; their popularity in Europe and their representation in Renaissance painting: you can read it here (it’s very good and full of images). These rugs are usually identifiable by their decoration, usually based on kaleidoscopic repetition of small motifs, central medallions, and their limited colour range dominated by brick-red. This particular carpet is a prime example of the production but according to the catalogue, it appears to be the only square carpet with a lobed medallion in its centre, usually this motif is applied to oblong pieces. Buyer’s enthusiasm for this rare piece can easily be understood, which is not necessarily the case for all the artefacts on this list!

19 – £1,855,000: A Gold Finial from the Throne of Tipu Sultan, c. 1800

Christie’s, 27 April 2023, lot 84: £300,000 – 500,000

If you don’t know who Tipu Sultan was, let me quickly introduce him, as you will see his name several times in that list (and you can be grateful it is only a top 20). Known as “the tiger of Mysore”, he was the ruler of the kingdom of Mysore from 1782 to 1799 (roughly the southern half of India at its largest). His reign is marked by conflicts with his neighbours, but mainly with the British East India Company, whom he fought all his life, sending emissaries to Ottoman Turkey, Afghanistan and France to gather forces against them. Ultimately, his efforts to limit the progression of the British in India were a failure, and he died in 1799 when British armies invaded the capital city. He was such a fierce opponent to the crown that his death was declared a national holiday in Britain, and the obsession for the man has continued ever since. This golden and gem-inlaid tiger head was part of the Al-Thani collection, which bought it at Bonhams in 2013 for £389,600. It was offered in New York in 2019 for $500,000-700,000 and remained unsold, until this year when it was valued roughly the same after conversion, this time achieving nearly 2 millions. This head was probably taken from the throne right after the death of the ruler and brought to England as a souvenir for Thomas Wallace (1763-1843), who was part of the Board of Control overseeing the activities of the East India Company. As we will see, a lot of Tipu’s memorabilia was taken from the palace immediately after his demise and passed to British collections, adding provenance to famous history.

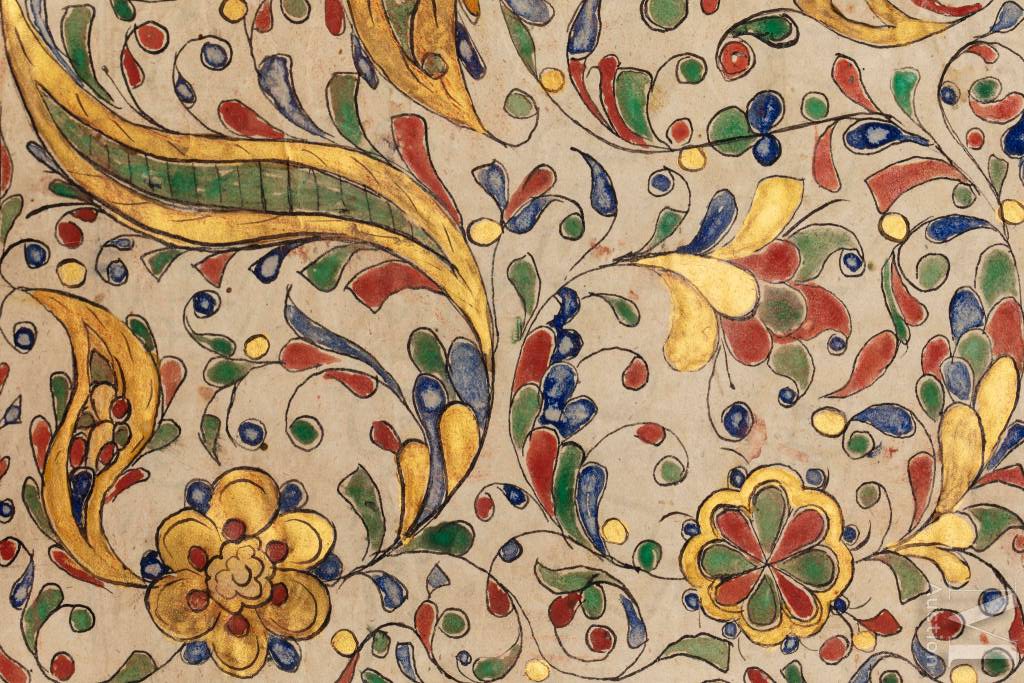

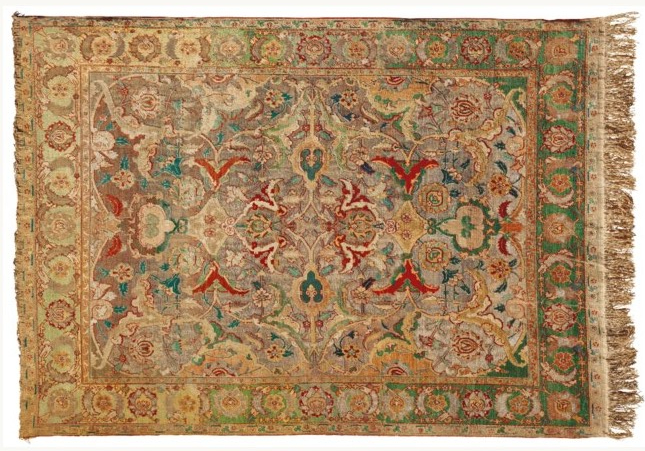

18 – 2,062,500: A Safavid silk and metal-thread “Polonaise” Carpet, first half of the 17th century

Christie’s, 1 April 2021, lot 129: £1,500,000 – 2,000,000

Polonaise carpets are normally quite rare on the market so they usually do quite well, as we will see in this list. The production of these carpets have little to do with Poland and everything to do with the Safavid ruler Shah ‘Abbas I (r. 1587-1629). After moving the capital to Isfahan in 1598, he launched a big campaign to modernise Persia textile industry, and used the Armenian community freshly deported from Julfa to Isfahan to develop a solid trade network with Europe. Polonaise carpets produced at that time were often sent to Europe to either be sold, or to be gifted to royal families to illustrate the finesse of Persia’s craftsmanship. For this reason, a lot of Polonaise carpets have a very prestigious provenance, such as this one which was initially in the collection of Prince Pio Falcó in Rome. Among the particularities of this production is the decoration, often repeated nearly identically on two or more pieces. According to Christie’s catalogue, this one has an exact pair in the Palazzo del Principe in Genoa, built for Andrea Doria in 1521.

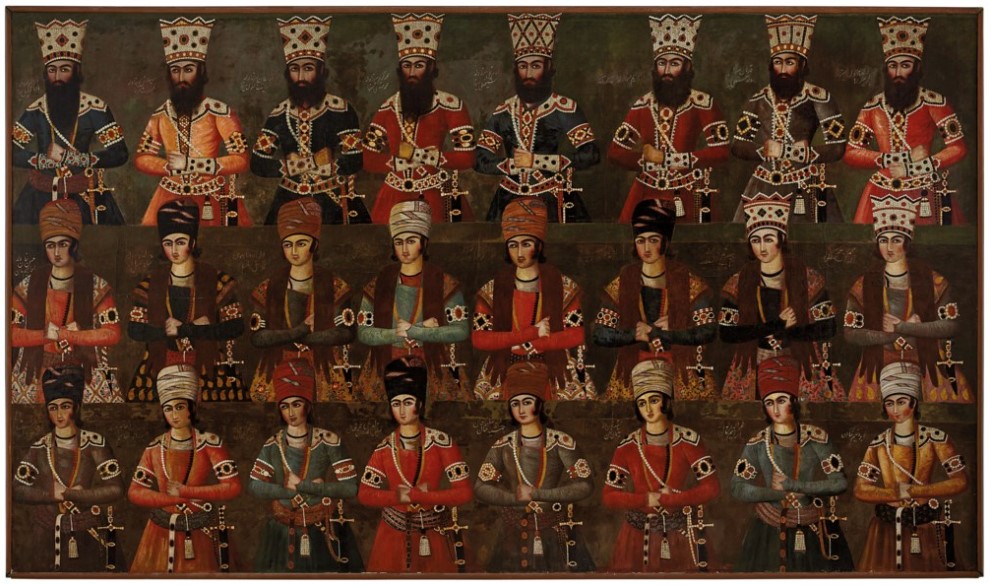

17 – 2,302,500: A Qajar Group Portrait, c. 1810-20

Christie’s, 1 April 2021, lot 30: £1,000,000 – 1,500,000

This massive painting, 2.565 x 4.42 meters, depicts twenty-four royal courtiers portrayed in three rows of eight, all standing facing left and wearing lavish robes and turbans or crowns, each figure identified. It was part of the Bonnet House Museum and Gardens in Fort Lauderdale, the summer residence of the artist and collector Frederic Clay Bartlett, and is truly unique occurrence on the recent market. It was probably made to decorate the walls of the Negarestan Palace, near Tehran, built in 1807 as a summer residence for Fath ‘Ali Shah, second ruler of the Qajar dynasty (r. 1797-1834). Christie’s bet big when offering this painting, and called upon Dr Layla S. Diba, great scholar of the period, to produce the catalogue essay. She did a phenomenal job that I will not paraphrase here, but I encourage all to have a look at it. Qajar painting is increasingly popular, however, and to my knowledge, it had never passed the million at auction. With a valuation at £1 million, this could have flopped dramatically. Instead, it made the list!

16 – £2,322,000: A Safavid silk and metal-thread “Polonaise” Carpet, first half of the 17th century

Christie’s, 31 March 2022, lot 174: £1,000,000 – 1,500,000

Christie’s seems to have a deal with owners of Polonaise carpets, as this second carpet is not the last one on the list. This one was in the collection of the Baron Adolphe Carl von Rothschild (1823-1900). Regarding the appellation “Polonaise”, it is linked to the passion of 17th century Baroque Europe for these carpets. Louis XV apparently owned 25 of them, but the Polish royal family developed a deeper fascination with Persia. As early as 1584, King Stephen Bathory (r. 1576-1586) bought 34 Persian textiles, and in 1601 a group of 8 Safavid silk and gold carpets was ordered by Sigismund Vasa III of Poland for his daughter’s wedding.1 The term itself was coined a lot later, during Paris Universal Exhibition in 1878 where examples of these carpets were exhibited in the Polish pavilions.

15 – £3,100,500: A silver-inlaid brass Basin, probably Herat, c.1200

Sotheby’s, 31 March 2021, lot 74: £1,000,000 – 1,500,000

This large basin of 50 cm diameter is particularly remarkable for its decoration. The twelve Zodiac signs sit in the bottom of the basin, each represented according to the iconographic codes developed in astrology literature, placed around the centre which features the planetary cycle, with Saturn in the middle, surmounted by the Sun, and clockwise – Mercury, Mars, the Moon, Jupiter and Venus.2 By itself, this piece is incredible, but when put back in the intellectual context of 12th or 13th century Persia, it becomes even more intricate and meaningful.

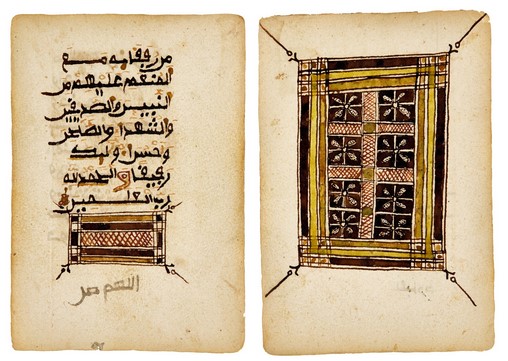

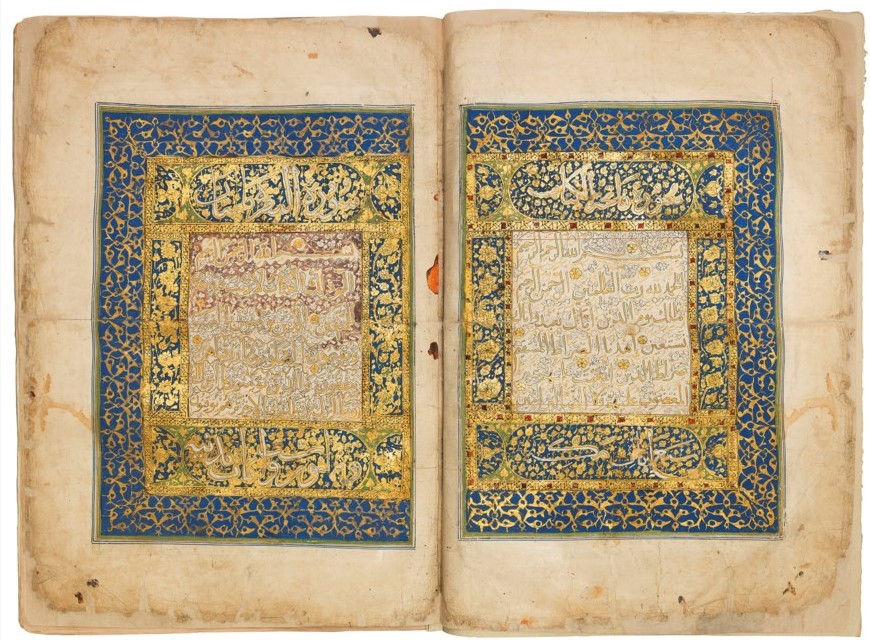

14 – £3,724,750: Qur’an dated 894 H./ 1489 made for the Sultan Qaytbay, Egypt

Christie’s, 2 May 2019, lot 11: £500,000 – 800,000

This is the only manuscript of this list, but also a head scratcher. While 14th century Mamluk Qur’ans are usually quite popular on the market and in academic historiography, the 15th century has suffered from a general lack of interest, and has fallen in an historiographical gap that is only starting to be filled. Among other things, the difference between the two centuries is linked to the change of style and, some would say, of quality, of the manuscripts produced. As noted in Christie’s catalogue, this Qur’an reflects a rapid execution, the calligraphy shows some irregularities and the illumination, nice from a distance, looks quite crude on some details (for instance the title band on picture 17 in the online catalogue: look at the layering of the reddish colour – it might be a repaint – and of the gold in the rosette underneath). The manuscript is a wonderful testimony of artistic patronage under Sultan Qaytbay, but was it worth more than £3 millions? I don’t believe so, but the market decides what the market decides.

13 – £3,724,750: A Safavid silk and metal-thread “Polonaise” Carpet, first half of the 17th century

Christie’s 2 May 2019, lot 255: £550,000 – 750,000

Yes, another Polonaise carpet sold at Christie’s, in the same auction as the Qur’an aforementioned. This one is described as: “With the Saxon Elector and later King of Poland Augustus the Strong. Reputedly gifted in 1695 to Lothar Franz von Schonborn, Prince-Elector and Archbishop of Mainz, Archchancellor of the Holy Roman Empire.”

12 – £3,737, 250: A Nasrid period ear-dagger, Spain, 15th century

Sotheby’s, 6 October 2010, lot 250: £600,000 – 800,000

This dagger is the only Spanish entry in this list. Nasrid objects are quite rare on the market and usually do quite well without exploding records, except for this one. The Nasrids were the last Muslim dynasty in the Iberian Peninsula, ruling from 1230 to 1492 over a decreasing kingdom. This dagger is a great example of the artistic productions in the Peninsula, but also of the cultural hybridity that characterises the period. Arabic and Latin inscriptions or pseudo-inscriptions decorate the “ear” grips, and the letters R and TT are carved in relief, which might indicate it was owned by a Christian or a Castilian-speaker. The gold was restored, which gives this piece a remarkable finish, and the catalogue entry did a great job relating this dagger to others dated.

11 – £3,895,000: A Safavid silk and metal-thread “Polonaise” Carpet, first half of the 17th century

Christie’s, 2 May 2019, lot 254: £600,000 – 800,000

The last Polonaise carpet in this Top20, and the last entry of the first half of the list. Sold with the previous one, it came from the same private Swiss collection and was initially owned by the Archchancellor of the Holy Roman Empire.

Honourable Mentions

To finish, I wanted to mention a few pieces that didn’t make the list but that caught my attention. Click on the links to access the auction catalogue:

A life-size portrait of Mughal emperor Jahangir, signed Abu’l Hasan, 1026/ 1617: £1,420,000

Bonhams, 5 April 2011, lot 322: Described as the largest known Mughal portrait, this gouache painting of Jahangir sitting on a throne holding an orb is nothing less than an oddity. It measures 2.10 x 1.41m (including calligraphic borders), a size never seen before and never seen since. Lots of eyebrows were raised at the time, including mines.

A bronze Cannon from the Gun Carriage Manufactory at Seringapatam, Mysore, late 18th c.: £1,426,500

Bonhams, 21 April 2015, lot 156: Initially valued at £40,000 – 60,000, this £1,4M canon illustrates the obsession of the market with Tipu Sultan. A large part of Bonhams auction was dedicated to Tipu memorabilia but for reasons that elude me, this particular canon broke records.

A Qur’an Scroll, signed Mubarak ibn ‘Abdullah, Eastern Anatolia, 754 H./ 1353-54: £1,602,000

Christie’s, 27 October 2022, lot 28: This extraordinary manuscript deserves its price. Valued at £250,000 – 350,000, it was beautifully exhibited at Christie’s alongside the wall of a small room where it could shine in all its glory. Its sale came with a bit of noise that didn’t go further.

A monumental bronze oil-lamp, Andalusia, 11th c.: £1,608,000

Sotheby’s, 26 October 2022, lot 93: Last but not least, this telescopic Andalusian oil lamp valued £300,000-400,000. This one is complete, with all its components present in a very good state of preservation. It is truly a technical masterpiece brighten up with exquisite decoration.

Stay tuned for part 2, coming soon!

- Axel Langer, The Fascination of Persia, Zurich, 2013, p.121

- To learn more about this iconography, you can start with Stephano Carboni’s catalogue of the MET exhibition “Following the Stars: Images of the Zodiac in Islamic Art” held in 1997 (in PDF, free)