Click here to jump to the latest update (22nd Nov.)

The challenges the world faces this year are of unprecedented magnitude, and with them, the fragile equilibrium of world economy has been thrown off balance completely. For museum and galleries, the blow is particularly hard, as most intitutions were already struggling keeping their doors open and their ceilling from leaking.

To Deaccession or Not To

In countries were main museums are public institutions, the gradual decrease of governement fundings have forced museums to look for funds elsewhere. In 2018-2019, the British Museum received £13.1 million grant-in-aid, the lowest since 2015, and particularly significant when put next to the year total expanditure, £96.2 million. This translated, among others, by an acquisition budget going from £1.1 million to £0.8.million. Last year, British Museum public revenues was £39.4 million, also the lowest since 2015, but we can expect 2020 to be particularly disastruous.1

For galleries and private museums, the pandemic and inevitable economical crash that is predicted for 2021 are even more worrying, and it will take some time to recover from the loss of public revenues. Around the world, cultural institutions and associations are forced to look inside for solutions. In April, the American Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) passed a series of resolutions to relax the rules of deaccessinioning restricted funds:

The resolutions state that AAMD will refrain from censuring or sanctioning any museum—or censuring, suspending or expelling any museum director—that decides to use restricted endowment funds, trusts, or donations for general operating expenses. The resolution also addresses how a museum might use the proceeds from deaccessioned art to pay for expenses associated with the direct care of collections.2

This means that between April 2020 and April 2022, American museums can sell parts of their collections to replace lost income and finance their operations.

In the UK, the powerful Royal Academy of Arts (RA) has been letting a similar idea float, though the debate has been particularly focused on the Taddei Tondo, a marble sculpture of Michelangelo, already threatened of sale in the late 70’s.3 No decision has been made yet regarding the tondo future, and it is unlikely that the piece will end up in an auction, but the financial crisis of cultural institutions, especially the smaller ones, might force hands.

Selling or exchanging pieces of collections to fund new acquisitions is not a new practice, American museums have been doing it for years in a controlled setting4, but the new guideline from the AAMD extends the justification for selling art pieces towards operational means.

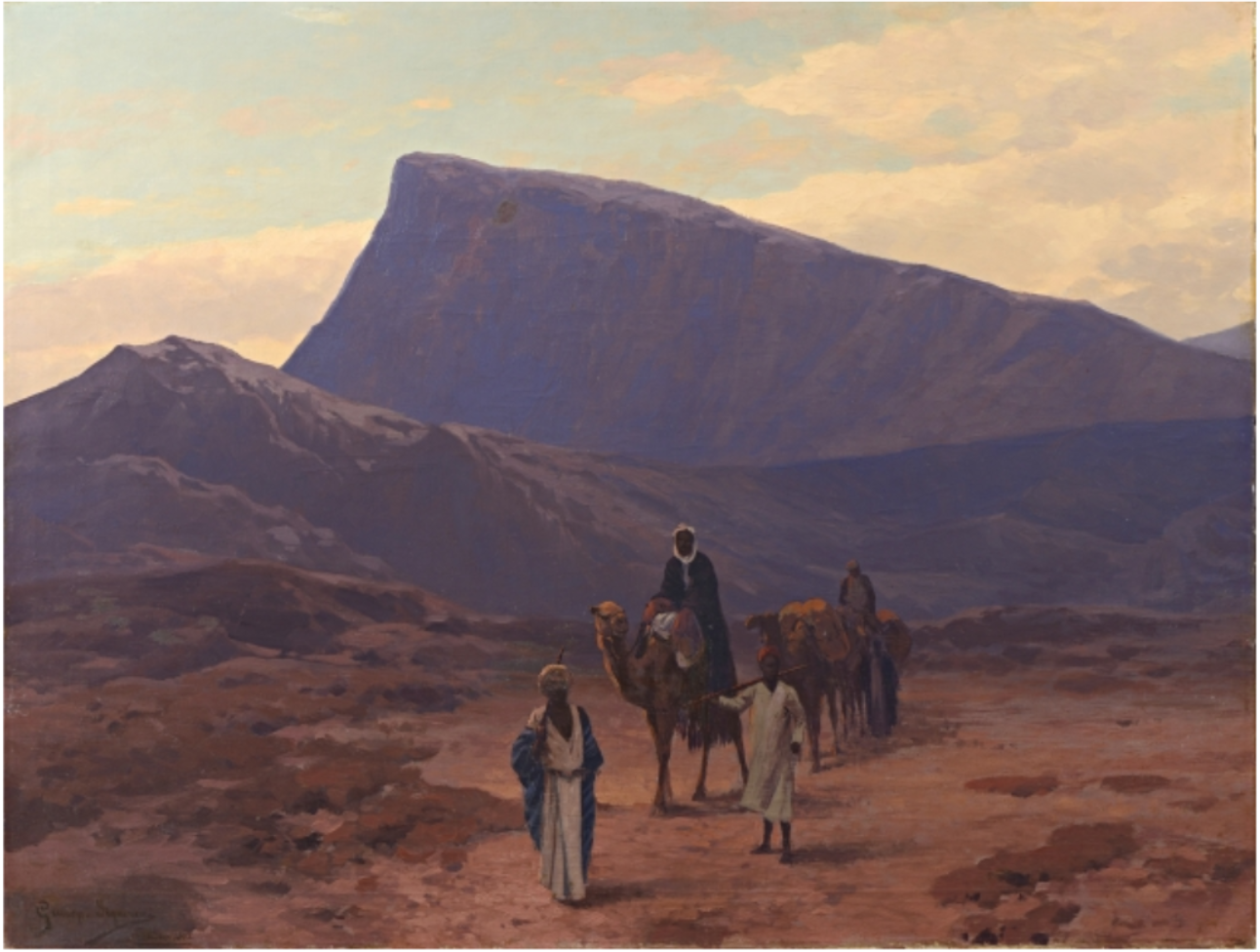

What it means for Islamic Arts

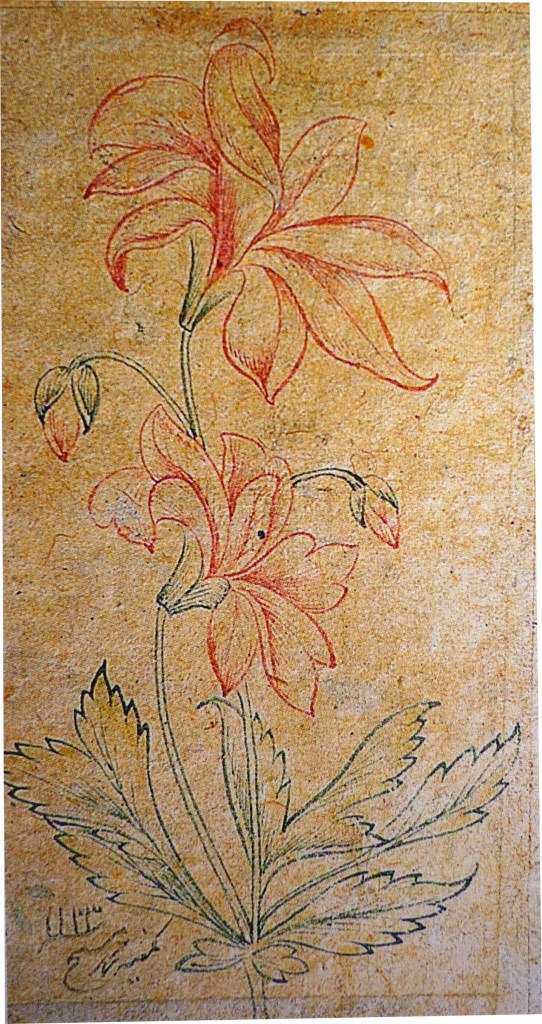

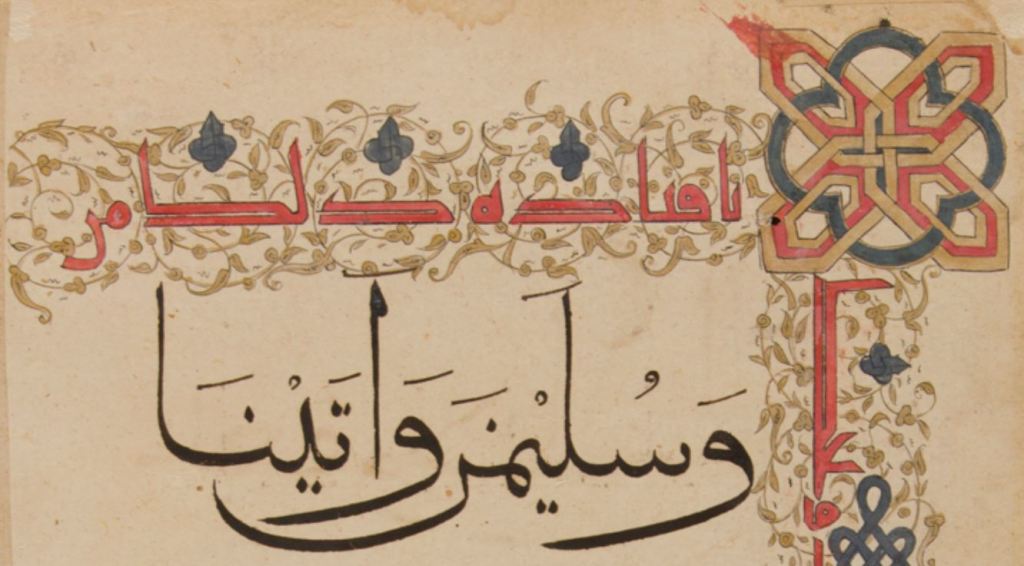

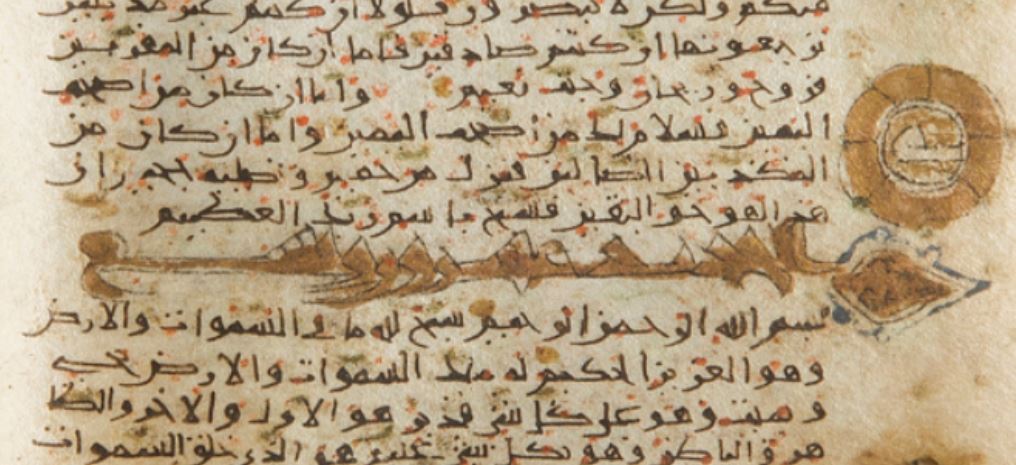

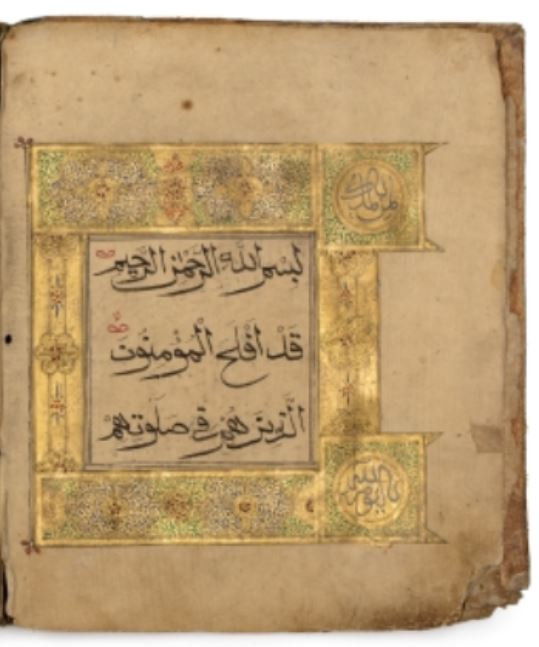

So far, Islamic arts had not been publicly impacted by deaccessioning, though the practice is common behind closed doors and emphasised by controversial sales such as the Timurid Qur’an on Chinese paper witht a more than opaque provenance, sold in June 2020.

However, in a market working in a quickly closing loop and given the current context, it was only a matter of time before parts of an Islamic arts collection be presented in a historical auction.

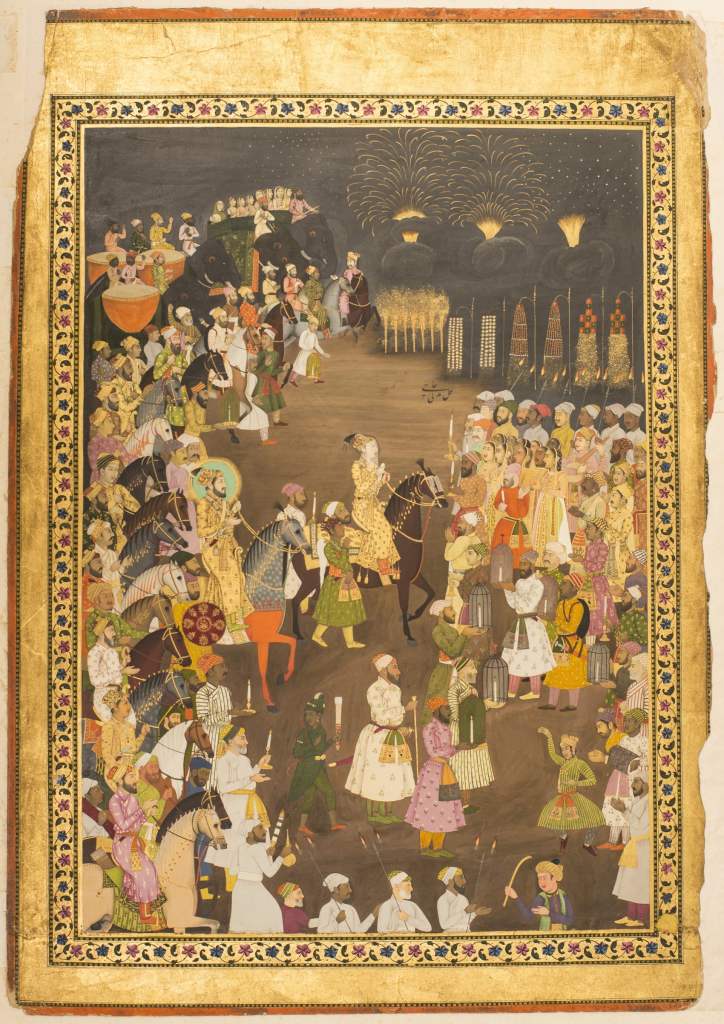

The time should have been on the 27th October 2020 and the auction at Sotheby’s of 190 lots from the collections of the L.A. Mayer Museum of Islamic Arts in Jerusalem. The aim of the auction has been clearly stated by the museum director Nadim Sheiban:

We were afraid we could lose the museum and be forced to close the doors. […] If we didn’t act now, we would have to shut down in five to seven years. We decided to act and not wait for the collapse of the museum.5

The catalogue included lots from all over Islamic lands but none from Israel and Palestine, as the legislation regarding native artefacts leaving the country is particularly strict. The auction, planning to reach around £6 million, would have given financial security to the L.A. Mayer Museum for the years to come, but would also constitute a definite slippery slope for private museums of Islamic arts around the world.

In an unexpected turn of events, the auction was postponed last minute on Monday night. While Sotheby’s website states that the delay is only until November, there is no guarantee the sale will ever occur, as criticisms came from the Israeli government officials and the public. The Hermann de Stern Foundation, that owns the L.A. Mayer Museum collection, still seems keen on moving forward with the sale but might struggle reaching an agreement:

The foundation’s management hopes that the postponement will make it possible to reach agreements that will also be acceptable to the Culture Ministry in the coming weeks.6

What now?

If the sale does go ahead, it will set a new precedent for the market of Islamic arts, as it will open the door for other museums to sell parts of their collections, either to acquire new items or just to keep the light on.

We can also question the motives for selling Islamic artefacts. The conflict between Israel and Palestine and the tensions in the Holy City between Jewish and Muslims come to mind in the case of the L.A. Mayer Museum auction and make the intervention of the pan-Israeli governement more surprising, but Islamic arts are political and ideological tools in more than one region. The Indian governement of Kovind and Modi might use this opportunity to accentuate their efforts to rewrite (not to say errase) India’s Muslim history, but even in Europe where far-right anti-Mulims parties are gaining more influence every day, progressiveley emptying Islamic arts collections could be a way to deny a shared past.

This bleak picture highlights the fact that selling Islamic arts bears a lot of weight, and publicly deaccessionning collections is not anodyne. Auction arts should use caution when selling museum pieces, but in this less than certain economical context, caution might already be gone in the wind. It will be interesting to see if the L.A. Mayer Museum auction goes ahead in November, and what the near future holds for Islamic arts.

Update: Auction delayed again

On Wednesday 19th December, the High Court of Justice has suspended the sale for two additional weeks, time for the L.A. Museum, Sotheby’s and the Culture Ministry to negotiate over holding a more limited auction with less high profile items, though these remain to be defined.7

- British Museum governance.

- AAMD Board of Trustees Approves Resolution to Provide Additional Financial Flexibility to Art Museums During Pandemic Crisis 15 April 2020.

- Royal Academy of Arts considers selling Michelangelo marble to plug financial hole—and not for the first time 25 Sept 2020.

- The Permanent Collection May Not Be So Permanent, The New York Times, 26 Jan 2011. The Indiana Museum of Art lists all the deaccessioned pieces since the 1930’s.

- Jerusalem’s Islamic art museum says it has to auction off part of its collection, The Times of Israel, 24 Sept 2020.

- Auction for Jerusalem museum’s treasures postponed at last minute, The Guardian, 26 Oct. 2020.

- High Court Delays Controversial Sale of Rare Islamic Artifacts by Israeli Museum, Haaretz, 19th Nov. 2020.