This spring, London Islamic Week will be focused on four auctions: Bonhams opens on the 29th March with a catalogue of 248 lots; the 30th March, Sotheby’s presents a catalogue of 169 lots; Christie’s on the 31st March offers 209 lots; Rosebery’s closes the week on the 1st April with a large catalogue of 456 lots including 104 antiquities. To learn more about Rosebery’s auction, you can listen to the ART Informant podcast episode with Alice Bailey, Head of the Islamic and Indian Arts department.

Chiswick will hold their Spring auction later in April, while Dreawatts Islamic department is on hold since the expert left.

I hesitated a while to write this short article, as I was unsure how to approach it. However, it seems interesting to take a look at the current status of London art market and try to make sense of it.

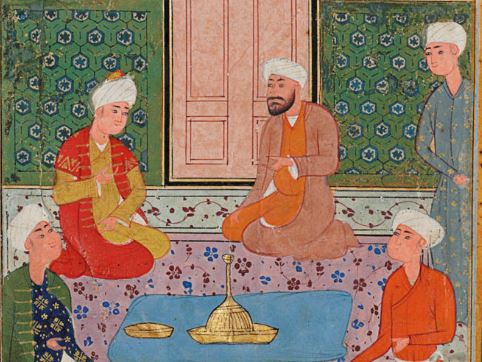

The highlight of the show is indubitably the page from Shah Tahmap’s Shahnama, offered by Christie’s for £2,5 to 4 millions. The valuation is justified given the fact that the last page from the same manuscript sold in public auction went for more than £8 millions.1 This copy of the Shahnama, the book of kings, was started for Shah Isma’il, first king of the Safavid dynasty in Persia (1501-1722), and was finished by his successor Shah Tahmasp. The paintings are the apotheosis of Persian painting for their refinement, iconography, technique… In short, seeing one of the manuscript’s pages is always an event, and I am particularly excited for it. Not many will be able to bid on the lot and I would not be surprised if it ended in Qatar or the U.A.E. Beside the beauty of the page, we can also applaud the neatly documented provenance.

For the specialists and aficionados of Persian carpet – which I am not, so I’ll keep this brief – Christie’s is offering a so-called Polonaise carpet for £1 million, which should also do quite well, as carpets seem to be of stable value.

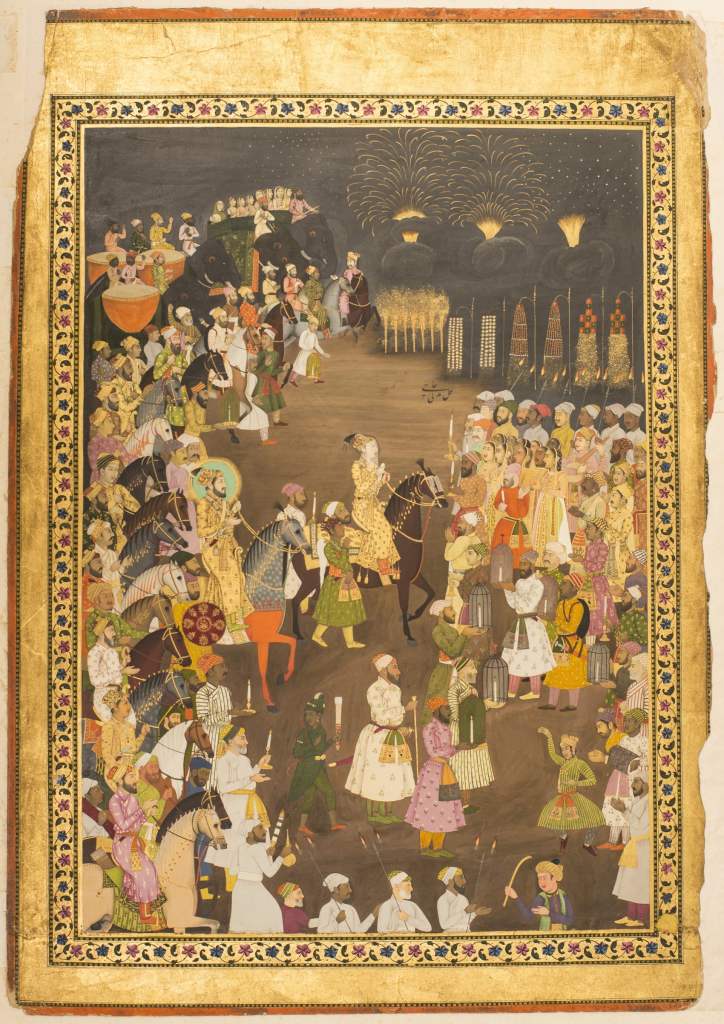

These are the only two items over the million. Sotheby’s biggest lot is a massive painting from early 19th century India, depicting the battle of Pollilur, which opposed Mysore armies led by Haidar Ali and the British troops of the East India Company. The whole composition is 978.5 by 219 cm and was most likely intended as an advanced preparative study for a mural. Offered at £500,000 to 800,000, the sale constitutes a peak for later Indian painting other than Company School2, and is definitely on trend with the current interest of buyers for 17th to 19th century Indian painting.

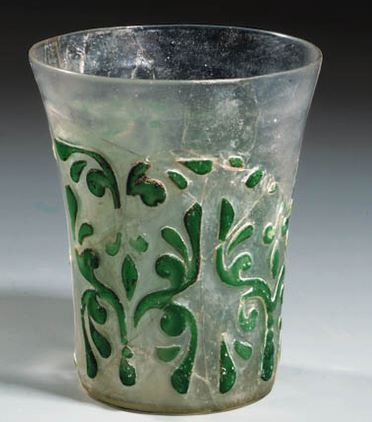

The huge gap between Christie’s and Sotheby’s create an imbalance echoed in the entire catalogue. The important size reduction of auction catalogues, almost automatically triggers an increase of prices, but some in Sotheby’s catalogue are very difficult to justify. A 13th century silver-inlaid qalamdan is offered for £200,000-300,000. The state of preservation is nice, and some silver incrustations have been restored, but the box isn’t signed nor dedicated, while the shape or decor are not particularly rare, so I fail to understand the valuation rationale. More debatable is the so-called Abbasid rock-crystal bowl, valued at £100,000-150,000. In a nutshell, I do not think this piece is Abbasid given the fact that all comparison pieces are either older or unjustifiably attributed to the Abbasid dynasty. The shape and decor of the bowl are a lot closer to late Sassanian dynasty productions than 9th century Basra, which leave me to question the valuation even further, given the fact that Sassanian pieces rarely sell well.

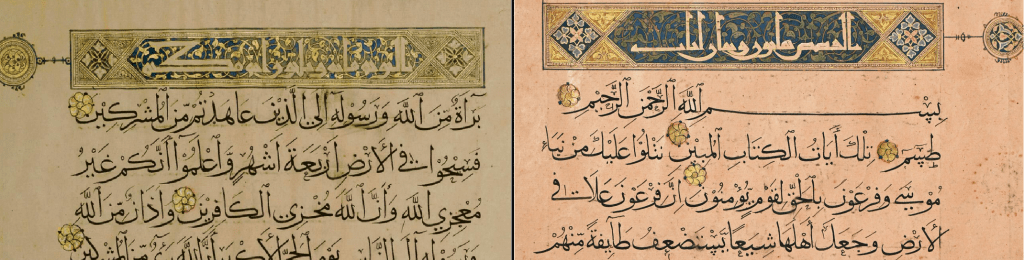

Some other prices are simply bananas (this is the technical terminology). How is a 16th century Safavid Qur’an with 19th century additions and lacquer binding given at £50,000-80,000? Same question with a non dated and unsigned 19th century Qajar copy of Sa’adi’s Kulliyat valued at £30,000-50,000. In comparison, Christie’s presents a similar but slightly bigger copy of the same text, with signed and dated illuminations and calligraphy, but valued at £5,000-7,000.

I am extremely curious to see if this artificial price inflation will convince buyers, or if they will give more attention to the less expensive but still quite interesting pieces that Sotheby’s is offering, such as a rare miniature Qur’an from Sultanate India (pre-Mughal), complete but in the wrong order, valued £10,000-15,000; the Indian Qur’an on green paper dated 1311/1893-4, valued £20,000-30,000, or the Abbasid dish with Kufic inscriptions, offered £20,000-30,000 but with no published provenance.

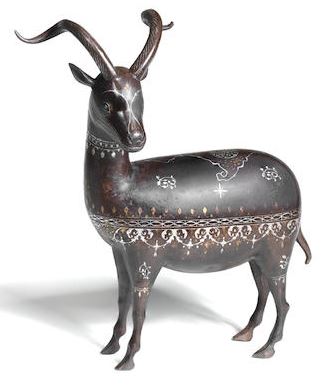

While late Indian paintings are getting some well deserved attention at Sotheby’s, Bonhams seems to be swimming against the current by focusing more than usual on Persian art, especially Medieval ceramics. Their top three lots are from Iran, starting with a silver-inlaid 13th century candlestick offered at £150,000-200,000. The second lot raises the same questions of dating and attribution as Sotheby’s so-called Abbasid rock crystal bowl discussed earlier. The beautiful bronze horse and rider valued £100,000-150,000 is given “early Islamic, Persia 7th/8th centuries”, which could be a possibility, apart from the fact that all comparisons given are either Sassanian, pre-Islamic, or Seljuk, 13th century. This doesn’t take from the inherent aesthetic quality of the piece, but Bonhams also has an annoying tendency to leave out provenance from their catalogue, which is risky with this type of already problematic pieces. The market will decide.

That being said, it wouldn’t be a Bonhams auction without late Indian art, especially Sikh, that plays in a very specific demographic and have been doing well in previous sales. A particularly interesting lot is the album of 60 paintings depicting Sikh rulers, monuments and people, most likely produced in Lahore in the 1840’s. The patron of this volume is not known (probably a British official given the English annotations on some pages), but its preservation state is quite rare and valuable.

The main item of this section is a lovely emerald and diamond-set gold pendant from the collection of Maharani Jindan Kaur (1817-63), wife of Maharajah Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), valued £60,000-80,000. Here lies the strength of Bonhams, its capacity to source exciting pieces with clear historical background and clear provenance.

For the same estimate, Rosebery’s is offering an imperial Mughal spinel, inscribed with the title of Shah Jahan and dated 1[0]39AH (1629-30AD), as well as other prestigious Indian jewellery from the late 18th and 19th century. Here as well, Indian painting is in the spotlight, as well as Chinese Qur’an with a selection of 14 ajzaʼ from different manuscripts. Alice Bailey, head of department, will speak about her auction better than I can, so go check the latest ART Informant episode!

After two years of pandemic, I am very excited for this Spring Islamic week, and look forward seeing all the incredible selections. If you’re in London between the 28th and the 30th March, get in touch and come say hi!

- Sotheby’s 31st May 2011.

- For reminder, the Great Indian Fruit Bat from the Impey Album sold last year at Sotheby’s for £644,200 incl. premium.