This spring is definitely a busy time for Islamic arts, the auction catalogues flow in the mail box!

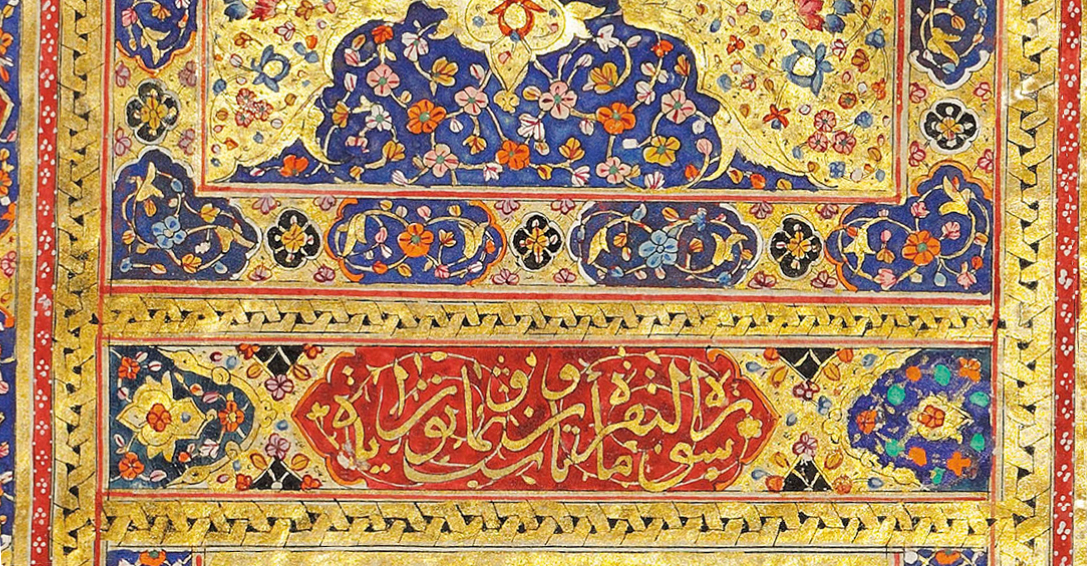

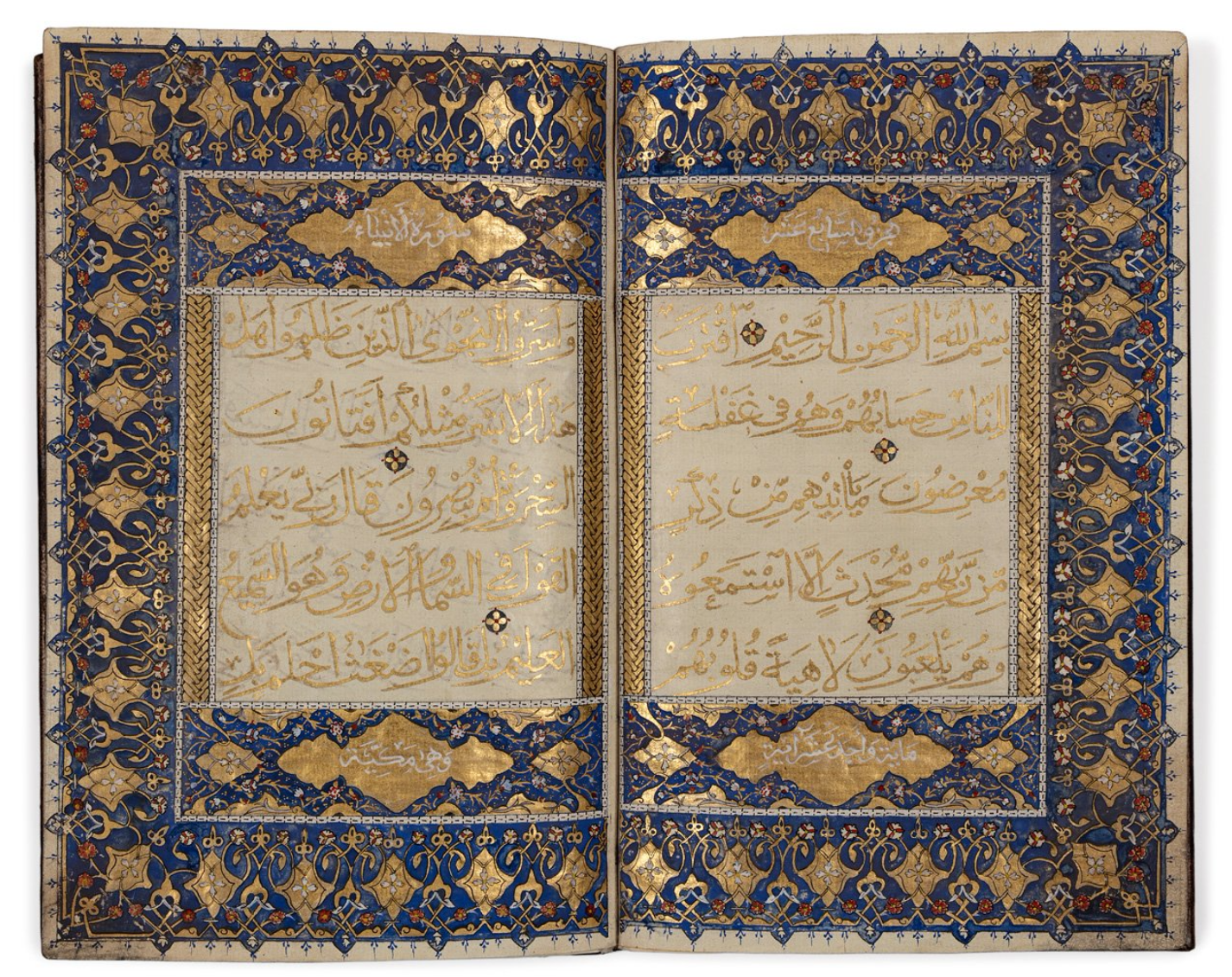

On the 3rd of May will be presented at Drouot Paris the Millon & Associés auction. I had the opportunity to work on one of the biggest item, a 17th century Mughal Shah Name linked to Jahangir’s reign and decorated with very interesting paintings and drawings. The full notice in English is available here.

The rest of the catalogue is equally rich, with a full first half dedicated to Orientalist paintings, as it is the tradition in Millon’s auctions. European paintings from the 19th and early 20th centuries depicting North Africa and the Middle East are not my field of expertise and I generally base my appreciation on their aesthetic appeal more than the overall production context. My three favorite among the 94 Orientalist lots are not the most expensive, far from it, but would compliment each other very well in a collector’s interior (not mine unfortunately!).

The Guardians of Henri Van Melle (1859-1930) are particularly interesting for their use of white and blue shades. The foreground show two men with darker clothes and dark skin on which shine the traditional Berber tattooed marks, both highlighted by the white and luminous architecture. Even though the pictorial technique of Van Melle is not particularly innovative, his understanding of light, shades and coloring gives a real interest to this painting, estimated 2500/3000€.

My second Orientalist favorite is a Moroccan night scene by Lucien Levy-Dhurner (1565-1953). I found the opposition of this painting and The Guardians fascinating, even though they are separated in the catalogue by more than 20 pages. While Van Melle worked on light, Levy-Dhurner worked on shadow but both being composed of different medium on blue shades. As well, both painters chose to depict a characteristic Moroccan architecture and a reduced number of figures. This is a common feature in Orientalist painting, that artists attached themselves to represent more of an idea than a specific subject, and these two paintings compliment each other perfectly in that sense. Levy-Dhurner painting is estimated 4000-6000€.

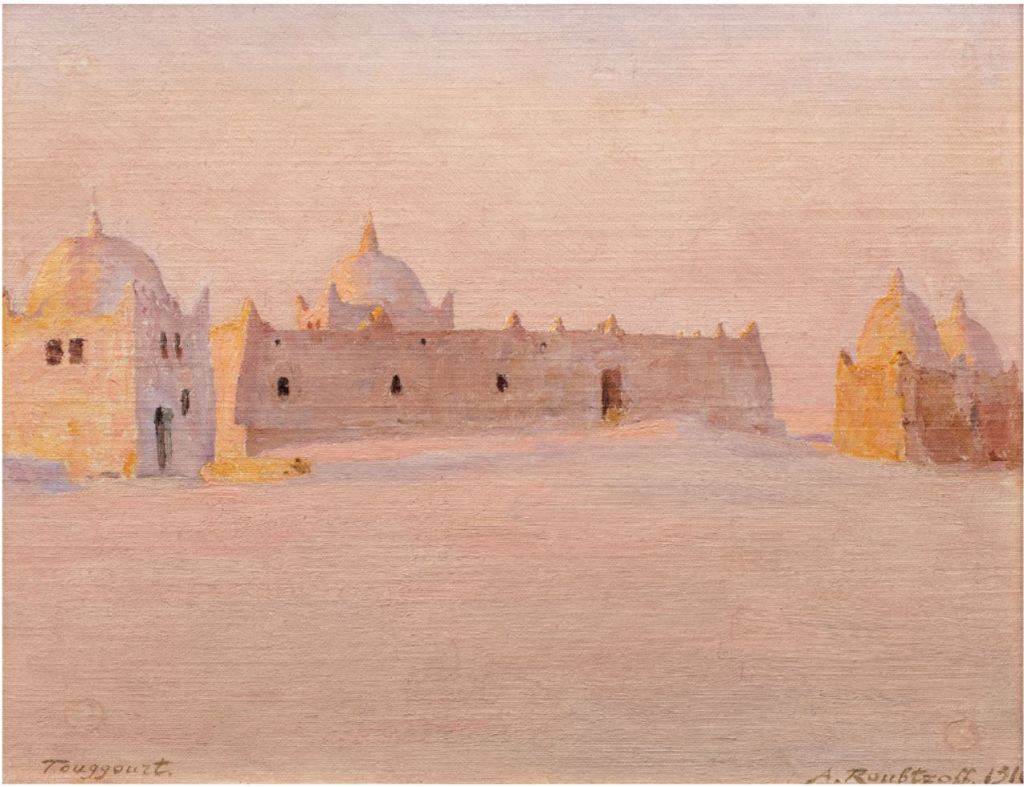

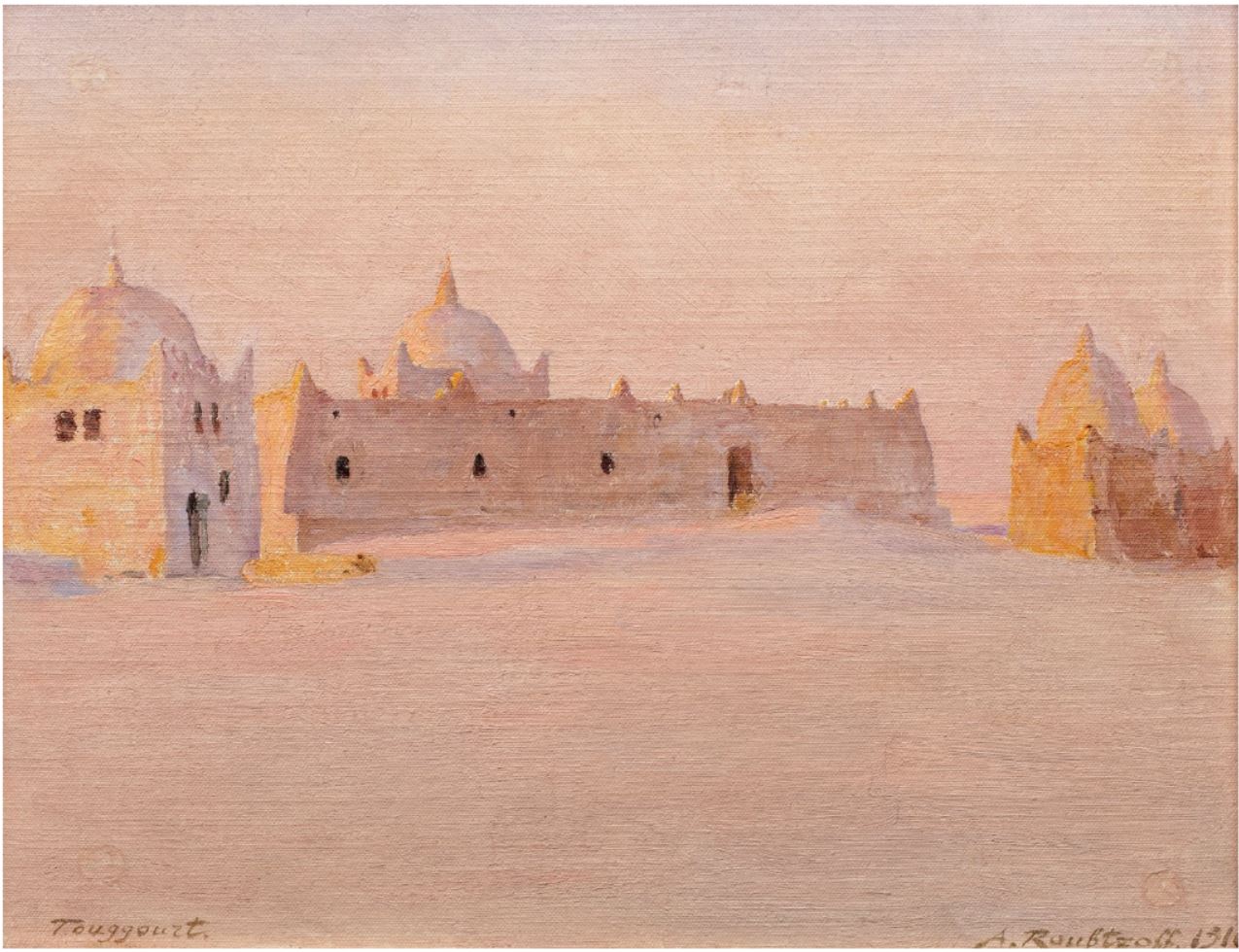

Finally, and in the same spirit, my last Orientalist coup de coeur is a view of the Beni Djellab tomb in Algeria by Alexandre Roubtzoff (1884- 1949), dated 1916. This elegant oil painting on cardboard depicts beautifully the desert architecture and shows an harmonious play on pink and orange shades. No human figure necessary here, just the calm poetry of the sunrise reflection on the sand dunes. This last painting is the most expensive of my tiny selection with an estimation of 5000/7000€, it is also the most appealing one.

The other half of the auction catalogue offers a diversity of items, ceramics, weapons, manuscripts, jewelry and textiles, with many interesting pieces. One of them in particular intrigued me. The shape of this powder-blue ewer is similar to Persian and Deccani (India) tableware. However, it was not produced in the Islamic world but in China, around 1720-1730, probably for the Middle-Eastern market.

Beside its aesthetic qualities embodied by the vibrant blue color and the original decoration of flowers and spider webs (a must on Chinese ceramics!), which earned it the estimation of 3000/5000€, I find this piece, and generally this production, particularly interesting for its historical value and the methodological questions it raises.

This particular ewer was produced in China for the Islamic market so, is it Islamic art or Chinese art? Is it even either, knowing that its shape was probably given to Chinese potters by European trade companies, already trading on a global level during the 18th century?

The search of authenticity by collectors of Islamic arts is legitimate and they could question the “truth” of this kind of items. After all, Islamic ceramics are not limited to shapes and uses, they encompass techniques, decorations and meanings. For instance, we can easily assume that the composition of this ewer differs from Islamic potteries, as Chinese potters have the ability to produce porcelain by adding kaolin to the paste, a material absent from the Islamic lands which mostly use siliceous pastes (80% of silicium in opposition to clay based paste mostly used in the Christian west before the 17th century).

In my opinion, the value of this kind of items lies precisely in their complexity. This ewer represents a very particular point in time, the moment when trade companies took control of the global market, both in Asia by setting up production workshops and in Europe by introducing on the art market fake Indian and Chinese productions coming from these workshops and presented as authentic products of exotic interest. In fact, shapes and decorative repertoire were created by the companies for these specific markets and were a mix of different artistic traditions, like this ewer showing a Persian shape and a Chinese decoration. This item is a pure product of artistic exchanges during the pre-modern era and a nice one with that!

I posted my last favorite item on Instagram, it is a real beauty and again, with great historical interest. Go check it out!

I look forward seeing the results of this auction, first to see if my work payed off but also because the prices achieved on this sale will certainly have an impact of the Parisian auctions for the rest of the year. Again, stay tuned!