I admit it, this title might be a bit dramatic, but it is still an accurate depiction of the upcoming Islamic week, as, yes, there are bats.

This year, Bonhams opens on the 25th October with a large catalogue of 342 lots, more than double since last Spring auction;

Roseberys presents on the next day with a head-turning catalogue of 557 lots, though not all are Islamic. Going through the selection is not easy, as there is such a thing as too much of a good thing, especially when the internal organisation of the catalogue makes no sense and the online navigation only allows keyword searches. That being said, a large part of Oliver Hoare’s collection is offered for sale and kept as a cohesive whole within the catalogue.1

Sotheby’s holds two auctions on the 27th, in the morning with 29 Company School paintings, in the afternoon with 184 lots, including three going over the million.

Christie’s presents a single catalogue of 207 lots on the 28th. Only one item goes over one million, and the catalogue gives the impression that the auction house has struggled to get a high-quality selection. There are still some pretty amazing and unpublished artefacts, so all is not lost.

Finally, Chiswick closes the week on the 29th with two catalogues, a single-owner sale of 162 lots in the morning entirely dedicated to 19th and early 20th Qajar Iran, and a larger catalogue of 236 lots in the afternoon.

All previous auction results include premium.

You can click on any image below to get to the corresponding catalogue entry.

The commodity of Indian art

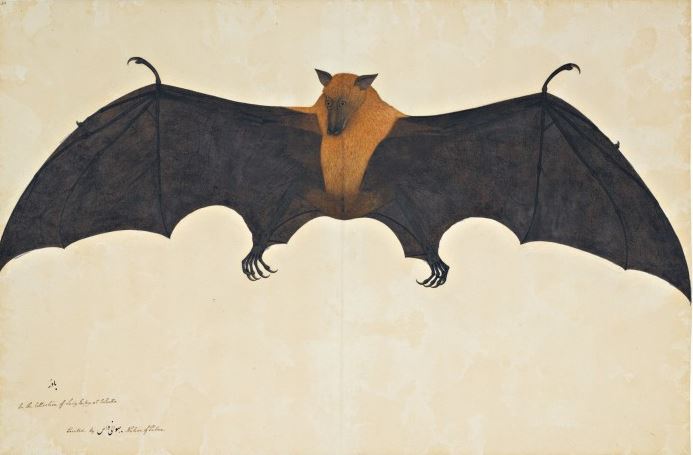

Let’s start with the bats. Sotheby’s first auction is exclusively made of Company School paintings, coming from the collection of the New-York gallery Carlton Rochell. Prices go from £8.000-12.000 to an astonishing £300.000-400.000 for a Great Indian Fruit Bat signed Bhawani Das, produced for Sir and Lady Impey. Elijah Impey was Chief Justice of Bengal from 1774 to 1787 and settled in Calcutta with his wife Mary, where they took a particular interest in hiring local artists to depict Indian natural history. They are today the most famous patrons of “Company School” painting, reflected here in the price of Sotheby’s bat. The flying fox was already famous on the market, having most recently been sold for £458.500 at Bonhams in 2014, before that for £168.500 at Christie’s in 2008 as part of the Niall Hobhouse Collection sale.

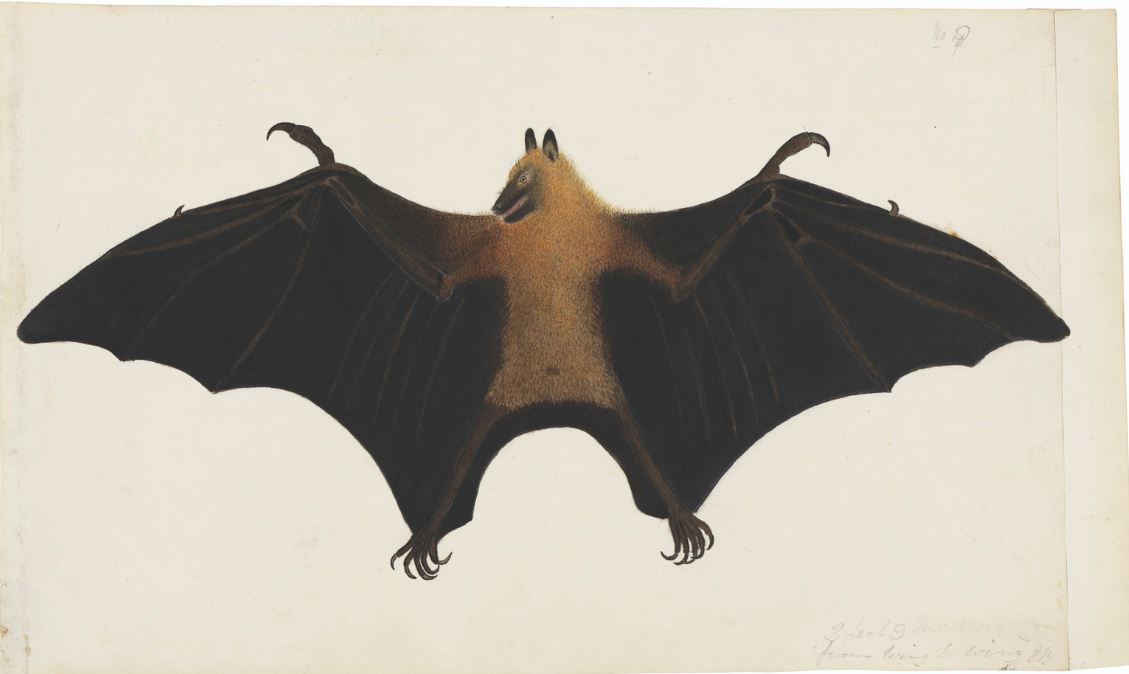

The second flying fox, presented at Christie’s for £20.000-30.000, appears a bit pale in comparison to the first one. Unsigned, it lacks the endearing realism that characterises Sotheby’s bat. As well, the catalogue only mentions one previous provenance and nothing prior to 2018.

Company School paintings haven’t moved crowds in a few years, and estimations rarely exceed £40.000. Sotheby’s is taking a risk by presenting a catalogue exclusively composed of Company School paintings, hence the clever marketing, betting on a foreword of William Dalrymple, famous author and curator of the exhibition Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company, held at The Wallace Collection in 2019-2020. It will be interested to see if the announcement effect bring new buyers, but we can at least expect the Flying Fox to do well.

Sotheby’s details the provenance of most of the paintings, which is always laudable, but was not particularly difficult in this case, the majority having been sold in the past 10 years on the London market, either in public auctions or in galleries such as Simon Ray and Francesca Galloway. Stuck in the close loop of increasing values, this leads to suspect that Sotheby’s Bat and Crimson Horned Pheasant are not collected for their artistic merits, but instead the safety their investment represents. It would be naive to think this is not the case for other, even any, high-value artefacts, but this is particularly obvious in this case.

What is also obvious in this auction, is the unofficial agreement between Sotheby’s and Carlton Rochell. Browsing through the afternoon auction catalogue, many Indian paintings rang a bell. With reason, as they were published not long ago in Carlton Rochell’s 2020 and 2021 catalogue, for instance lots 141, 146 and 147 (as I’m finishing this article, Carlton Rochell’s website has been down for two days, and I didn’t get the chance to download the catalogues to compare with Sotheby’s any further. The site was working on the 5th October when I started writing. As we say in French, mystère et boule de gomme).

Indian glasses?

Moving from bats to elephants (the ones in the room), Sotheby’s presents two pairs of 19th century spectacles set with emerald and diamond lenses, each valued at £1.500-2.500.000. I am not a lapidary specialist, so my opinion is solely based on the catalogue, and let’s say I’m confused by these objects. The emeralds originate from a mine in Colombia discovered in 1560, and it is stated in the text that large quantities of emeralds were subsequently acquired by the Mughals. This seems to contradict the fact that emerald deposits can be found in Afghanistan and India. The diamonds “most probably” came from Golconda, but this is not confirmed. Aside from the stone’s origins, the main issue is that the frames are described as European. Indian stone-setting techniques are mentioned in the text, but it is specified that “they incorporate a European ‘open claw’ design”. Examples of figurative paintings showing Pince-nez glasses are also given, such as a portrait of Aurangzeb2, but these spectacles are not pince-nez. The valuation is probably justified by the stones, but the catalogue is extremely misleading, as these beautiful spectacles might very well not be Indian at all. Golconda diamonds and Colombian emeralds on a European frame raise a lot of questions, but I let the reader forms their own opinion.

Metalwork in the Place of Honour

The debatable spectacles are not Sotheby’s high-value lots, the first place goes to a gold and silver inlaid brass candlestick attributed to Mosul circa 1275, offered for £2-3.000.000. Previously sold in Paris in 2003 for a price I was unfortunately not able to retrieve, it was exhibited in the MET from 2017 to 2021. The inscriptions do not give any information on the production context, but the subtle iconography suggests a court commission.

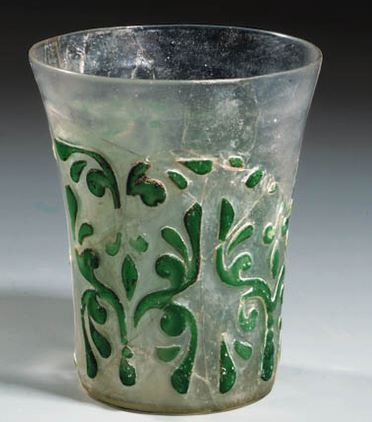

The same way, Christie’s second-biggest lot is an elegant brass ewer attributed to the Khorassan region c. 1200-1210, valued at £ 300-500.000. Bonhams presents a few early bronzes, including a horse-shaped censer. The piece had previously been presented by Christie’s in 2006 as Byzantine and sold for €20.050, but is rebranded here as Umayyad and valued at £100-120.000. The line between Byzantine and Umayyad is often so thin, deciding on one over the other becomes a marketing question. Early Islamic usually sells better than late Byzantine, but it also involves more risks. Clearly, Bonhams feels confident enough to give a 6 figures’ valuation.

Not to be outdone, Roseberys and Chiswick offer a large selection of metalworks. Roseberys presents 12 lots composed of gold elements set with garnets and two similar rings, attributed to 12th century Iran and valued between £2-300 and £2-4.000 (lots 309-320). My guess would be that the gold elements come from two different ensembles, but the 10 pieces would deserve to remain together.

From what I could see (again, navigation is really uneasy), their most expensive metal artefact is a 12th century Seljuq bronze incense burner in the shape of a bird, valued £20-30.000. It is close to another burner in the MET, though Roseberys’ is better preserved.

My personal favourite presented at Chiswick is an engraved brass casket attributed to 12th century Sicily with later modifications, offered for £4-6.000. The complex history of the Sicily kingdom makes attributions particularly tricky, and art market professionals tend to stay away from the region, complex to brand and sell. It will then be particularly interesting to see if buyers are willing to invest.

Historical Figures, Historical Manuscripts

Chiswick main attraction in their afternoon auction is a group of 11 ivory figures depicting the Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his court, probably produced in Delhi in the first half of the 19th century. The central figure is identifiable, which is quite rare for this type of artefacts, but not unique in the case of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, as demonstrated by another ivory figure in the Victoria and Albert museum. The identification and the overall quality of the ensemble easily justifies the valuation at £25-30.000. To be noted that a second group of ivory figures is presented by Chiswick in the same auction, 13 anonymous palanquin bearers and attendants, valued only £6-800.

The same way, Bonhams most valuable artefact is a gold-koftgari steel repeating flintlock from the personal armoury of Tipu Sultan, signed by Sayyid Dawud and dated 1785-86. The provenance is no less prestigious, the weapon was acquired by Major Thomas Hart of the East India Company, following the siege of Seringapatam, and kept in the family until March 2019. I would not be surprised if a museum decided to acquire this piece, while Bonhams continues to establish their authority on historical artefacts.

Christie’s is betting big on historical figures this season, with their highest valued lot being six portraits of Ottoman sultans produced in Venice around 1600 for the Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha. The ensemble is very interesting, both for its historical value, but also for the inherent dynamism and quality of each portrait. It seems risky to put European paintings as showrunner of an Islamic art auction, but I believe these will do well.

My favourite item of this entire Islamic Week is a Qur’an produced in Sultanate India, both signed and dated 838/1435, which is extremely rare. Offered by Christie’s for £30-50.000, the valuation doesn’t seem to fit the quality of the manuscript. That being said, Sultanate manuscripts rarely fly, so it will be interesting to see what this one will achieve. The gorgeous illuminations are characteristic of Sultanate Qur’ans, an odd mix of Egyptian and Persian influences, interpreted through then Indian lens.3

To finish, and speaking of rare, Sotheby’s present a complete Chinese Qur’an in 30 volumes, signed and dated 1103/1691. This is a huge event, and I hope the specialists of the field will have the opportunity to rush to London to see it before it is sold. Chinese Qur’ans are almost always dismembered, juz being sold separately, while dates and signatures are art history unicorns. The manuscript is sold without provenance, which is highly problematic, and I sincerely hope Christie’s will open their archive to scholars (which they usually do).

So much more could be said about this Islamic week, but I’ll stop there before rewriting all the catalogues. What do you think about Bonhams, Roseberys, Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Chiswick selections? Please share in the comments below!

- Oliver Hoare (1945-2018) was an influential Islamic art dealer, to whom we owe the creation of the first Islamic art department at Christie’s. More info on his Wikipedia page.

- Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin, inv. I4594 fol.5.

- The lot essay finally quotes Pr Brac de la Perriere’s work, one of the few specialists of Sultanate India and who has been mostly ignored in previous auctions. It was about time!