When I started studying Islamic Arts History, many years ago, many people asked me the same question: Why are you studying Islamic Arts? Are you a Muslim?

I always replied the same thing, being Muslim is not a requirement to appreciate the unalterable beauty of Cordoba Mosque, not more than being Christian to be moved by Michelangelo Pieta.

Islamic Arts history is an important and still underated branch of arts history, and a lot of misconceptions are still floating around, especially in the West, about what it is, what it intails and how we can talk about it.

For this reason, I’ve decided to introduce a new section on this blog, dedicated to this particularly facinating field of inquiry. To do so, I will focus on specific artifacts or groups of artifacts that present a historical or theoretical interest, thus retracing the history of Islamic arts. I can’t guarantee that articles will be in chronological order, I am letting myself being led by inspiration, but hopefully, it will make sense in the end.

Without any further due, let’s get cracking, we have a long way to go!

- First thing first, what are Islamic arts?

The short answer is pretty simple: are called Islamic all forms of arts created either in lands where Islam is the predominant religion or as a religious art. The distinction between the two is important, because not all Islamic art was created by Muslim, and not all Islamic artifacts were linked to religion. Roughly, the expression emcompass all art produced since the 7th century to this day, from Spain to India.

The expression “Islamic art” was invented in the early 20th century by European and American scholars and collectors to define a bulk of unfamiliar art forms. From there was created a specific field of inquiry, very soon to be questionned.

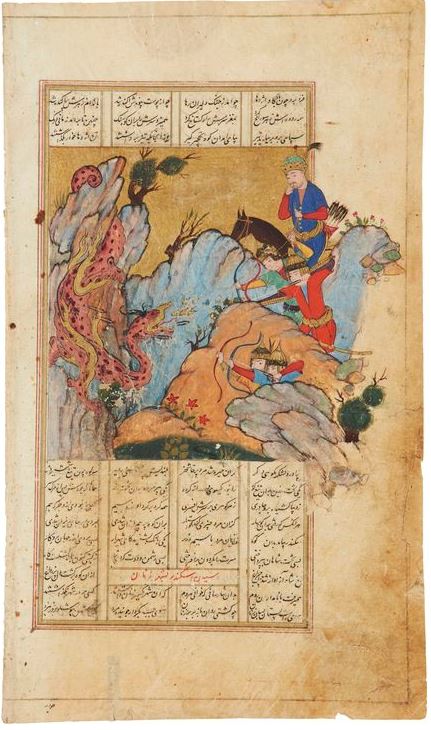

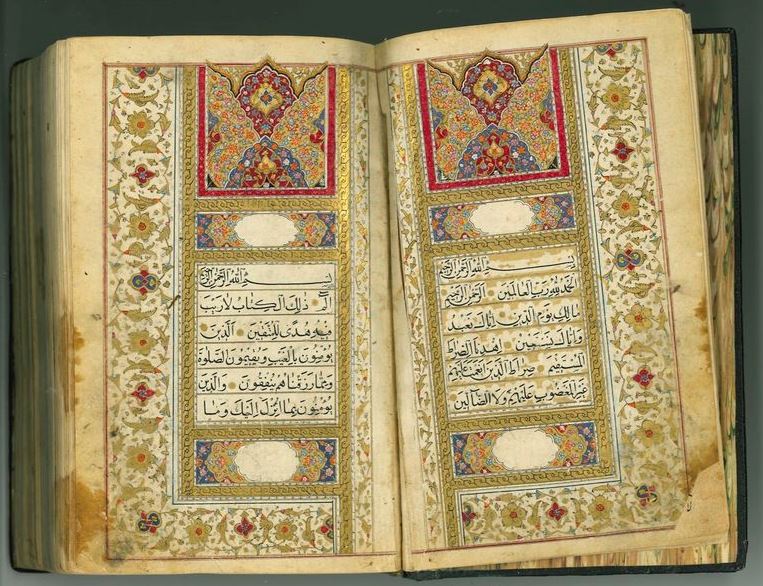

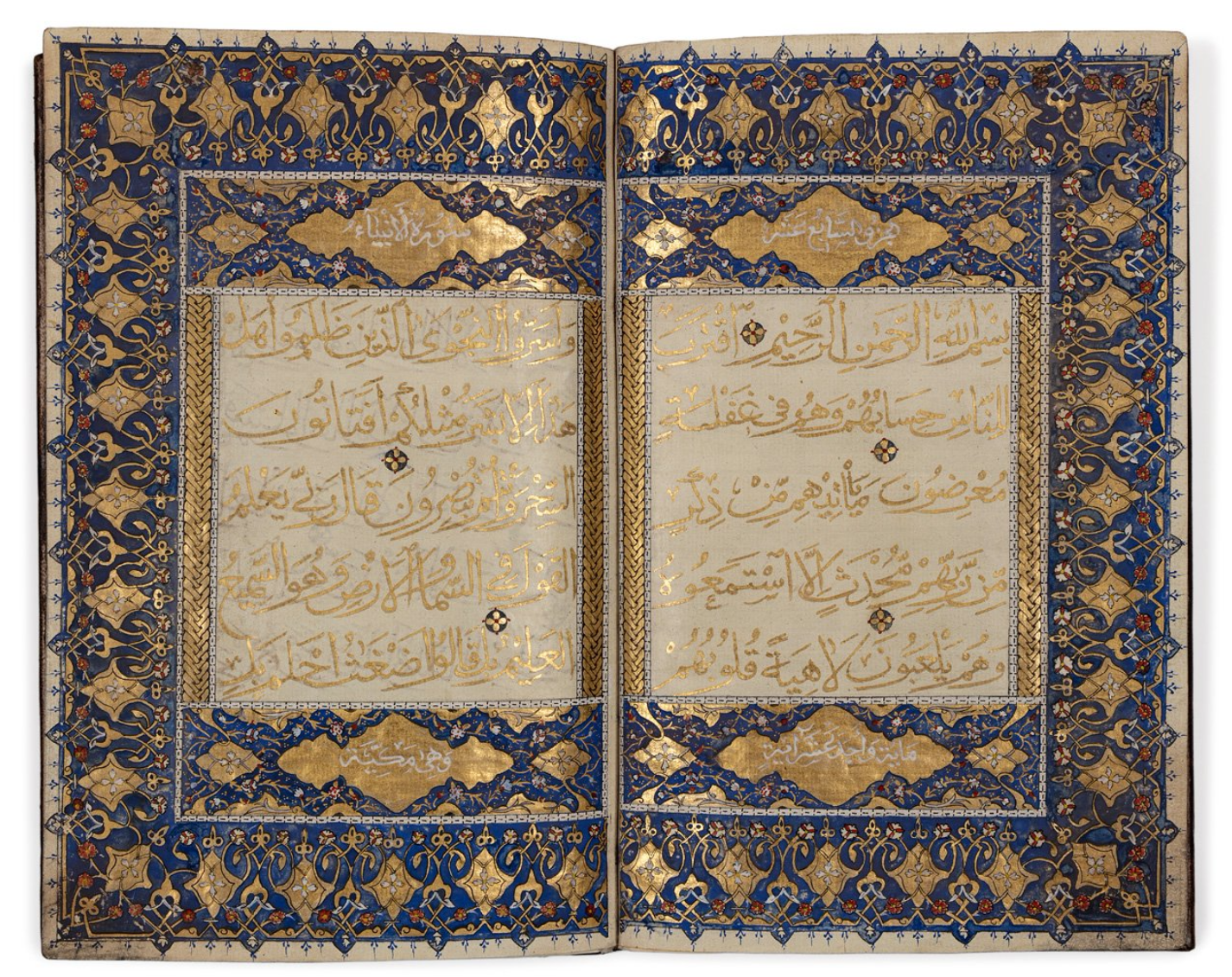

Indeed, with the rise of nationalisms in the first half of the 20th century, scholars from the Islamic lands opted to use more nationalistic names to define their field, for example Turkish art or Persian art. These terms are misleading on their own, Persian, for instance, can refer to a 15th century Timurid Qur’an or to the bas-relief of Persepolis, one of the capital city of the Achemenid dynasty dating back to the 6th century B.C.. The lengh of Islamic arts chronology, as well as the multiculturalism of Islam make these national distinctions really uneasy.

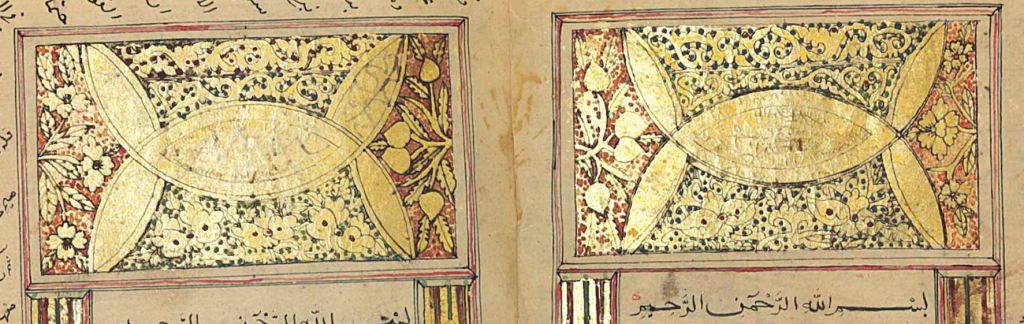

More recently, academics have questionned the term of Islamic arts as too general, since it doesn’t refer to a particular era, region, or even culture nor medium. To facilitate discussions, they have started to use regional or dynastic categories. For instance, the Mamluk of Egypt, the Safavid of Iran, the Umayyad of Spain etc. Though this fragmentation is very usefull, it doesn’t reflect the similarities and common features running through the Islamic lands like the use of Arabic language and the importance of calligraphy, or shared devorative patterns.

Christie’s 2015

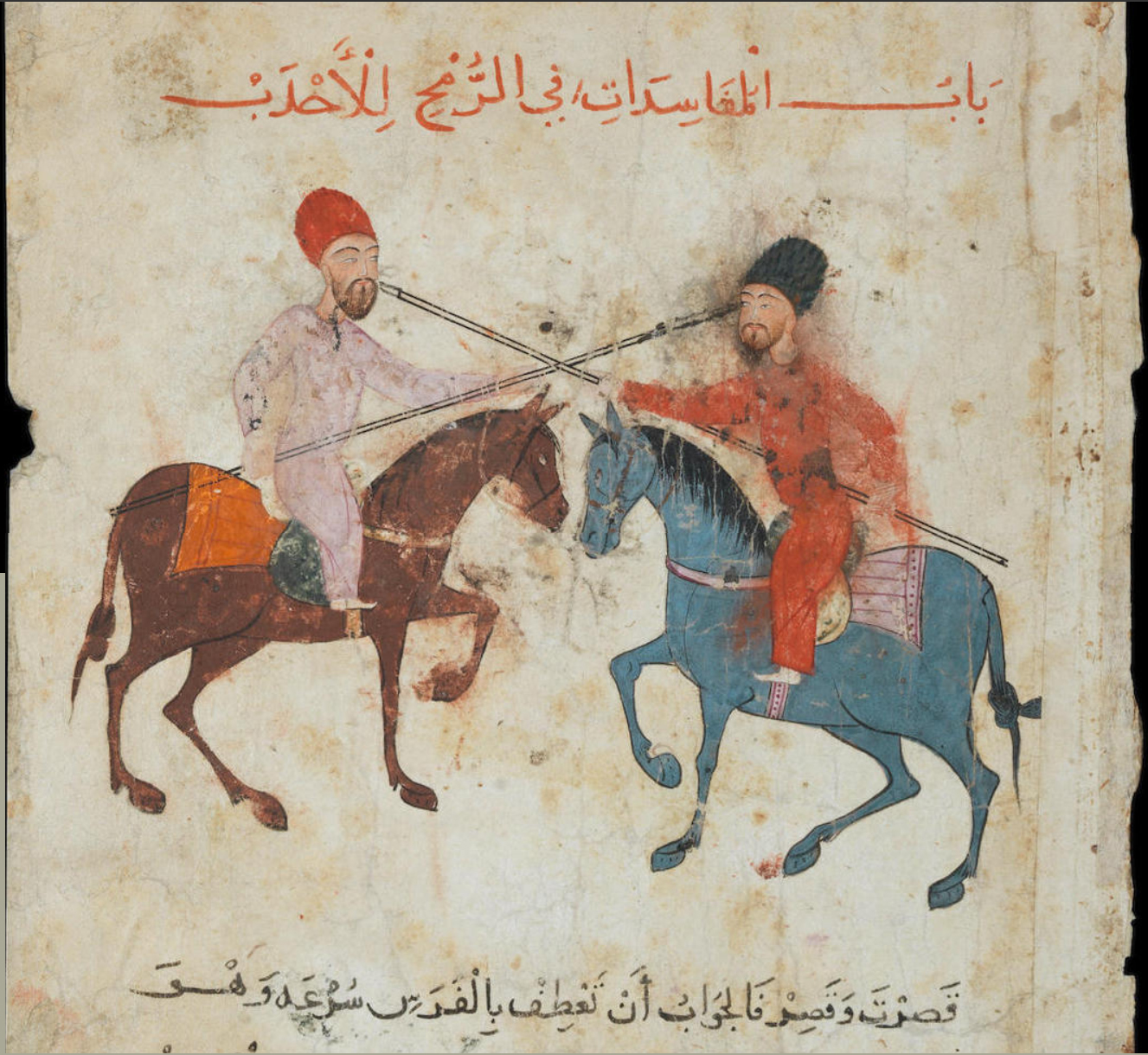

This division can be problematic because transmission is at the base of Islamic arts and this is what I will try to demonstrate in my next posts. Islam as a religion was born in a land crossed by many cultures and religions, either polytheist Arab tribes from the Nejd desert, Persians, Ethiopians coming through the Red Sea, Byzantians etc. When a new form of art, linked to the new power established after the Hegira, came to be needed, Arabs just had to look around and adapt existing forms to their needs. For this reason, we find today coins from the Umeyyad dynasty, the first Islamic power in the Middle-East (664-750) looking rather similar to Byzantine money.

Cultural transfers didn’t stop there, of course, and continued to define the core of Islamic arts through the centuries. Though its definition is still fluctuent, we could say that the main characteristic of creation in Islamic lands is the mastery of transition. It would be very easy to talk about “classical” eras of Persian painting or Mamluk architecture, but I do not believe them to be a truthful reflection of the constant artistic turmoil, the artists neverending quest for innovation, nor the genuine open mindness to the rest of the world.

These are some of the main features flowing through Islamic lands. For this reason, and others that I will have the opportunity to mention, Islamic arts bear a special importance for the understanding of past and present cultures and forms of expression, as they have touched so many of them.