Autumn is always an exciting time. Business starts again after a well-deserved break, calendars are getting busier and attention gets directed towards the next big event: the second Islamic Week in London. Finally, the catalogues are out and we get to speculate on what will sell the most.

This fall, I found that Bonham’s, Sotheby’s and Christie’s selections are full of surprise. They confirm tendencies that were already visible in the spring auctions but also seem to announce new trends; let’s jump in!

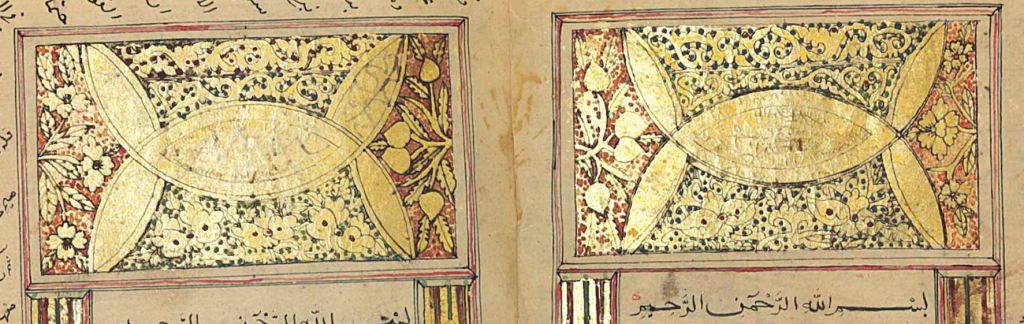

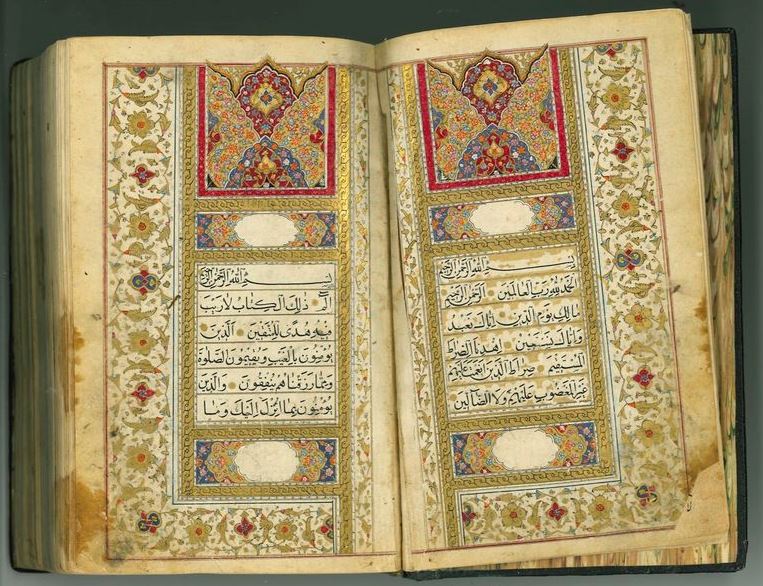

Bonham’s opens on the 23rd by skipping altogether the traditional section of 8th-9th centuries Qur’an leaves on parchment. Sotheby’s, on the 24th, heavily reduces this section as well. We find ourselves wondering if this change is due to the material running dry or if we are witnessing an increased disinterest from merchants and collectors. No noticeable breakthrough has occurred in the field since François Déroche published his study in the 90’s and collectors might be getting cold, especially considering the enormous mass of material which looks exactly the same. That being said, Christie’s, on the 25th, opens its auction by a page from the blue Qur’an, this enigmatic manuscript probably made in Tunisia around the 9th century. Pages from the Blue Qur’an are sold very frequently, the last one just last year, but valuation never seems to drop, this one reaching £200,000-300,000. Three other lots of the same sort are presented at Christie’s, including one of 67 consecutive folios, previously presented at Sotheby’s in 2007 for £60,000-80,000 and sold £60,500. Christie’s shows caution and give an estimation of £40,000-60,000. The result might disappoint the seller, but future will tell us more about this possible disavow.

Other interesting tendency shared by Bonham’s and Christie’s, the quantity of Safavid tiles. Bonham’s has 8 lots, Christie’s has 6 including one of 19 pieces presented together, another one of 2. The items chronology covers mostly the 17th century, with a few later additions. London auctions often present this kind of Safavid tiles, but the quantity is unprecedented. Safavid ceramics is generally less represented than its Ottoman counterpart, but we might see here the beginning of a fluctuation. To be confirmed next spring.

Speaking about Ottoman ceramic, it is impossible not to talk about Sotheby’s main event: a blue and white Iznik pottery charger, produced circa 1480. I am not particularly fond of Izinik ceramics, I admit it freely, but this one seems to be an absolute beauty and I look forward seeing it “in the flesh”. Though Izinik blue and white were designed to emulated Chinese porcelains (as seen by the hatayi flower arabesque on the rim and the reverse), their decoration have rapidly evolved toward a characteristic “Ottoman style”. This plate shines by the perfect balance of the rumi motifs interlacing and the subtle yet definite palette of white and blue shades. Yes, I am in absolute awe. Unfortunately for me, with its valuation at £300,000-500,000, I will have to settle for a brief admiration before the piece goes to someone else.

Sotheby’s presents quite a lot of Iznik pieces – the kind I don’t like – and I wonder if the current state of the Lira will have an impact on sales.

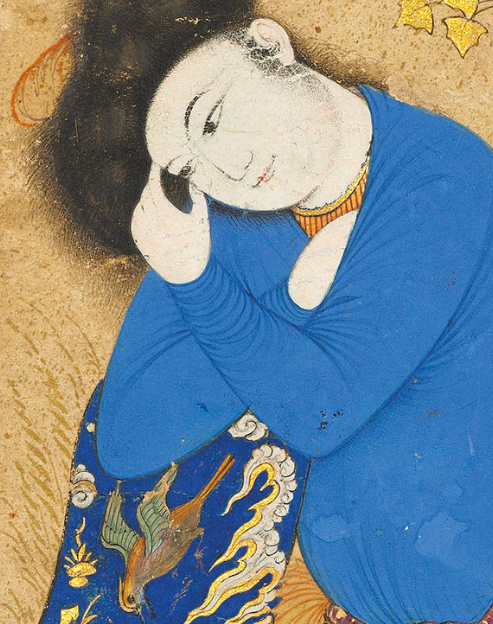

While Sotheby’s focuses on ceramics (another Ottoman ceramic ensemble reaches £300,000-500,000), Christie’s clearly put the emphasis on manuscripts and paintings. I will start with the obvious: Reza ‘Abbasi Seated Youth. I wrote my first year Master degree on Reza ‘Abbasi and developed a real admiration for this painter, known for his bad temper and love of street fights as much as his undeniable talent. For those who may ask (no one, they reply), I worked on the impact of Armenian art on Safavid painting during the reign of Shah ‘Abbas Ier, starting with Reza ‘Abbasi and this curious piece of archive kept in the Holy-Saviour cathedral in the New Julfa (Isfahan). Written in an elegant naskhi, it states that Reza ‘Abbasi received a training from the famous Armenian painter Minas but that the Shah should never know. Though this memoir wasn’t particularly successful, it taught me how to appreciate these delicate representations of an insouciant youth (and humility, also).

Valued £100,000-150,000, the painting is signed but not dated. I am always careful with dates when it comes to Reza’s work, but this painting can be compared to the one of A young Portuguese dated 1634, in particular in the depiction of embroider textiles. As well, the painting bears the mention to the patron, Mirza Muhammad Shafi’, mentioned on other paintings by Reza’.

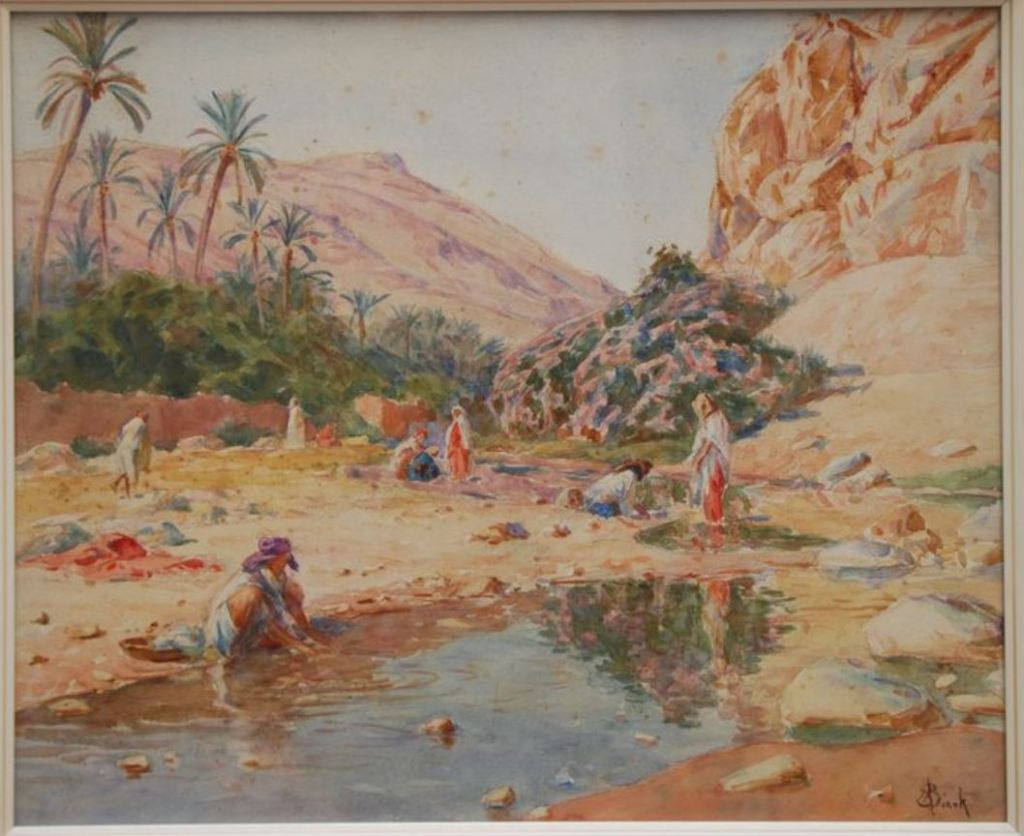

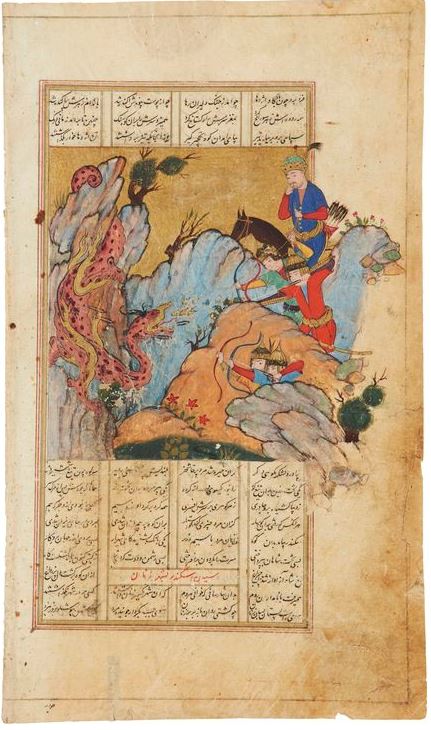

Christie’s shows a very interesting range of manuscripts and paintings and it would me take me days to comment them all. Instead, I will give a few honourable mentions. The first one is a page from the Chester Beatty Tutti Nama, produced in Mughal India around 1580-85, during the reign of Akbar (lot 172). Its estimation is surprisingly low, only £8,000-12,000, though the page seems to be in good condition considering its turbulent history.

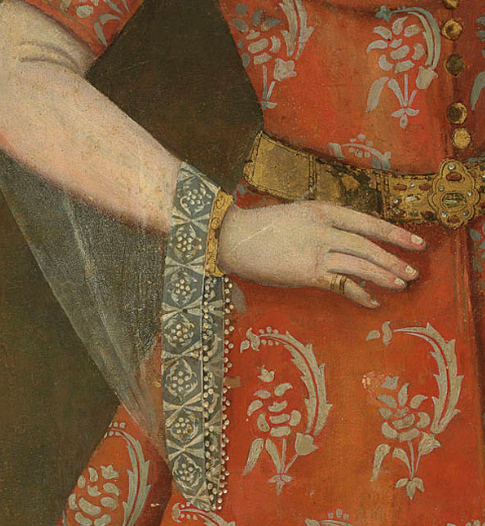

The second one is a Safavid oil painting, valued £40,000-60,000 (lot 100). Part of a group of panel first published by Eleanor Sims in 1976 (Persian and Mughal Art, 1976), the format is still quite unusual and surprising for the 17th century. These life-size panels (1,66m with the frame) were probably destined to decorate one of Isfahan palaces, but beside a few European primary sources and engravings, we really don’t know much about them. None of them being signed, my guess is that these paintings were produced either by Armenian painters or by Persian painters under Armenian patronage. The rendering of fabrics on this panel is particularly clever and reveals a clear impact of European pictorial practices.

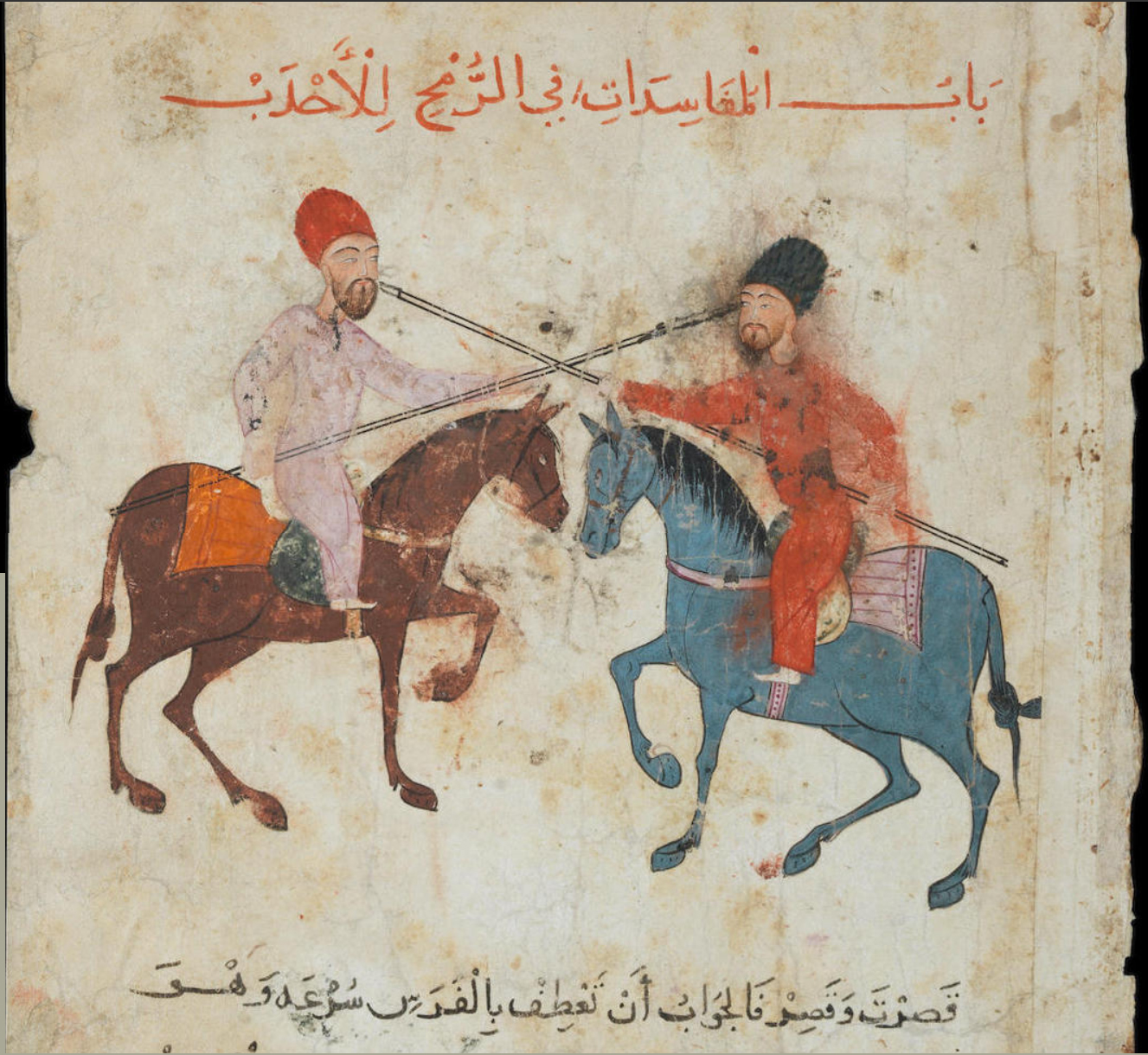

The last honourable mention goes to an elegant Qisas al-Anbiya produced in Ottoman Turkey during the 17th century (lot 238). Ottoman painting has finally started to get some recognition these past few years in academia, but also on the art market as we’ve seen last spring with the erotic manuscript sold at Sotheby’s for £561,000. The present manuscript was written in Farsi in an elegant nasta’liq but the 23 illustrations were undoubtly produced by a Turkish painter. It has already been sold at Christie’s in 2008 for £102,500 so it will be interesting to see what value it achieve ten years later.

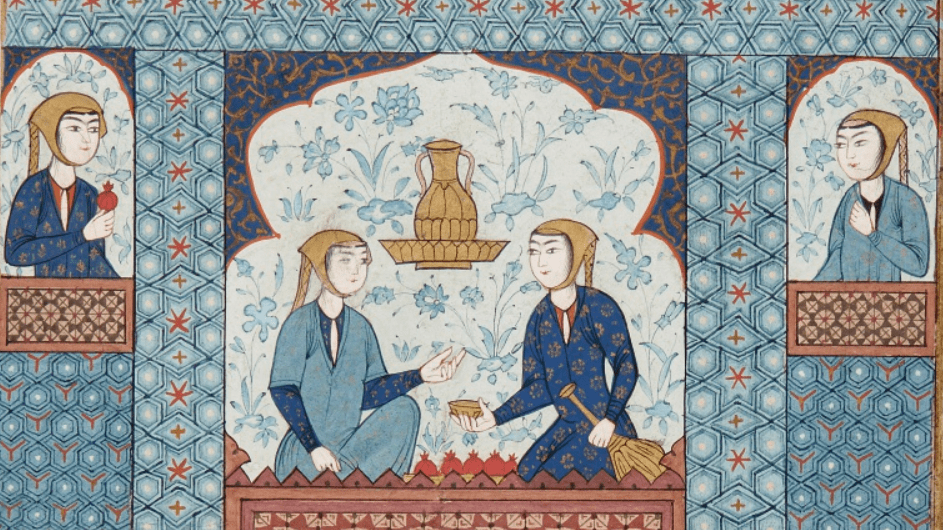

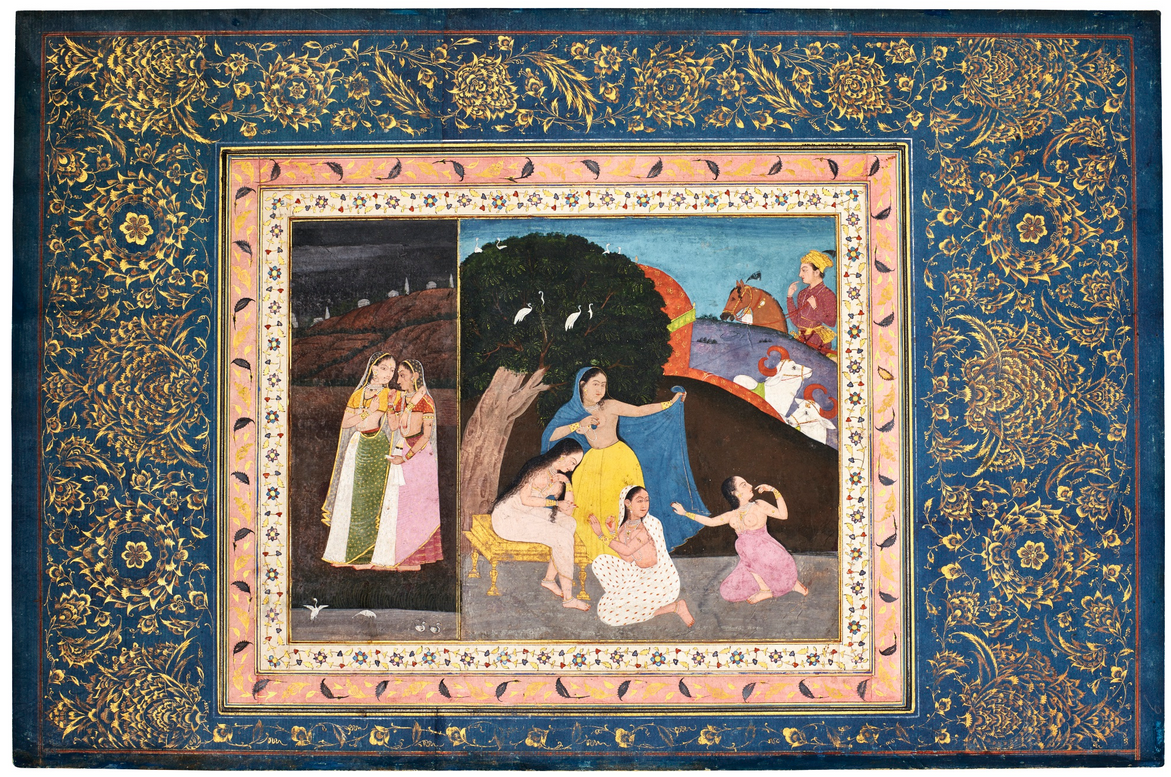

Sotheby’s presents a few interesting manuscripts and paintings, including one that left my baffled. The lot 94 is presented as a page of the St Petersburg album (also called Leningrad album) and is valued at £20,000-25,000. The central field shows a 17th century Mughal depiction of Farhad spies Shirin bathing on the centre right and two women conversing on the right. The assemblage is mounted in large blue borders decorated with a golden floral arabesque. In theory, it looks like it, but I strongly disagree with this attribution for three reasons:

– The sizes don’t match: The St Petersbourg pages are 47,5x33cm, the Sotheby’s page is 46,8×30,8cm for a ratio margins/central field that seems similar. The Sotheby’s page doesn’t seem to have been trimmed, it still shows the outer line delimiting the border decoration. If the page was separated after 1910, as the catalogue suggests, then there is no reason for it to have been trimmed. This discrepancy can only be explained by a different origin.

– The decoration doesn’t match other pages from the album. Given, the page ornementation could be unique, it happens elsewhere in the album. That being said, all the pages with blue margins show consistence in their layout, especially the use of a golden line delimiting the ornamented field. On this page, the delimitation is a thick red band framed by golden line that doesn’t appear anywhere in the album. As well, the density of the arabesque design and its palette – two types of gold or gold and orange (to be confirmed de visu) doesn’t fit the rest of the album. The inner borders decoration doesn’t correspond neither, especially the colour theme of their background: pink and white, where the album shows a dominant of bright red, deep blue or gold.

– Finally, in the St Petersbourg album, all pages with blue margins are calligraphic sides, not figurative. This is an absolute constant and there is no way this page could have fit in this album with these margins, as it would have broken the internal balance of the volume.

Persian muraqqa’ can sometimes appear like a random gathering but in most volumes, especially those produced for an influential patron, there is always a logic in their layout, content or decoration. David Roxburgh has already demonstrated this for Timurid and early Safavid albums (The Persian Album, 2005), while Adel Adamova has worked on the Leningrad album (Medieval Persian Painting, 2008). Shamelessly promoting myself, I have also worked extensively on the album for my doctoral dissertation, especially its flower paintings and floral decoration. In my opinion, Sotheby’s experts got a little bit too excited with this page. It might have been produced for a slightly more recent album in Zand or Qajar Iran, but certainly not for the Leningrad’s.

I will finish this long article by mentioning the very interesting selection of Sikh artefacts offered by Bonhams from lot 200 to 220. The exhibition of the Toor collection, In Pursuit of Empire, held in London from July to September this year, along with the incredibly beautiful and rich exhibition catalogue, have shed a refreshed light on Sikh art, and it will be interesting to see if collectors follow.

A lot will need to be discussed after the auctions, and for those who would fancy a direct chat prior the auctions, I’ll be in London from the 23rd to the 26th. Feel free to get in touch!