I cannot believe 2024 is already here. It seems like this year has flown by, but I’m saying that every year. On a personal note, 2023 has been a strong year, full of positive moments, but that has also demanded a lot of resilience and hard work. I already know 2024 will also required a lot of focus and dedication to be able to manage it all, but I’m excited about it.

But enough about me! What happened on the Islamic & Indian art market this year? In short: a lot, and because the year went so fast, I thought now would be a perfect time to review the key moments of the British and French auction houses that have brought us so much excitement.

Let’s rewind the year, but not necessarily in chronological order as this has proven to be a bit monotonous to write (and I’d assume to read). After that, I’ll give you some of my predictions for 2024!

All the prices given below include buyer premium.

Key moments of 2023 in London and Paris

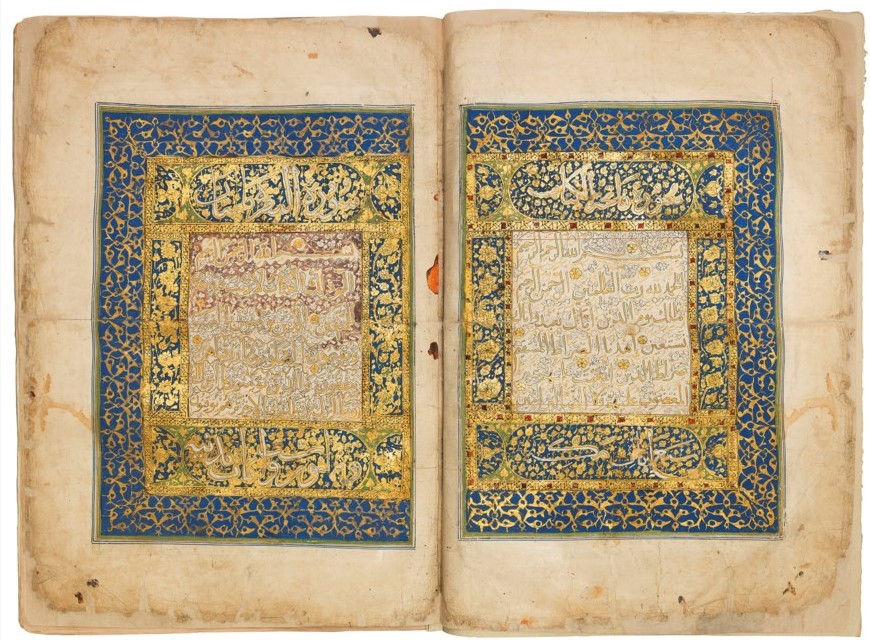

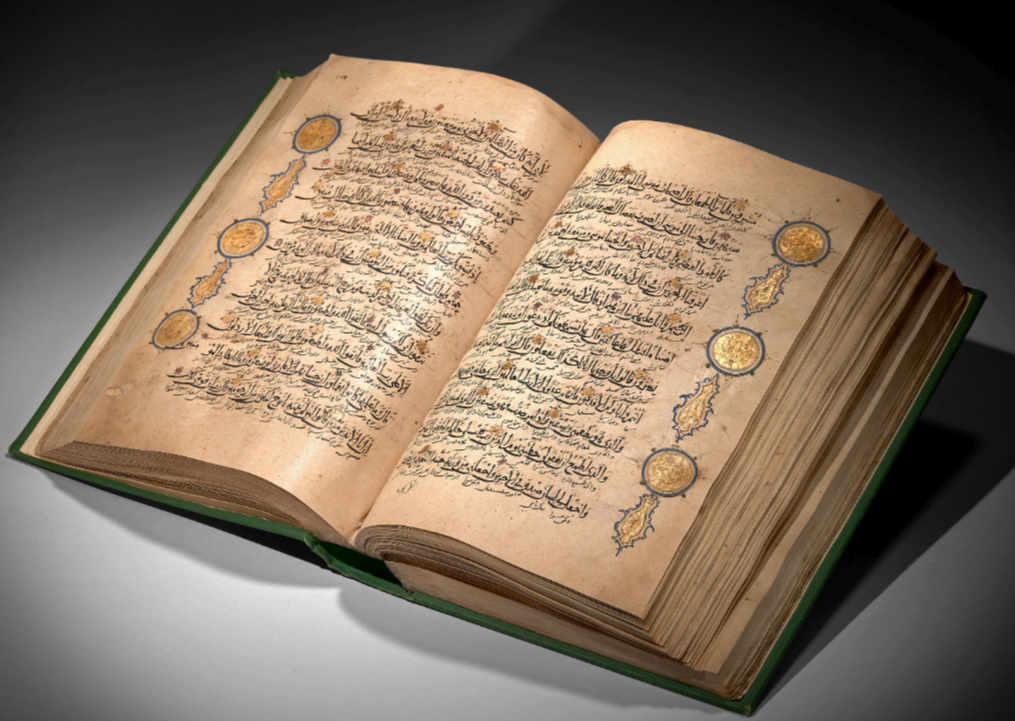

The market year started in February with two back-to-back auctions by Ader which included many Indian paintings that sold quite well. In hindsight, this gave the tone for the sales to come. In February, an Ottoman Qur’an juz from 15th century Anatolia valued at €8,000-12,000 sold for €96,000. In March, the highest result was with two Company School paintings of the Taj Mahal and the Buland Darwaza valued €6,000-8,000 and sold for €30,720. Both auctions achieved a total of €1,105,422, to which were added €299,654 from a third sale in July of the collection of famous French collector Philippe Magloire, bringing the total for the year to €1,405,076, a 325% progression since the previous year (during which only one auction was held), and put Ader on the third place of the French podium.

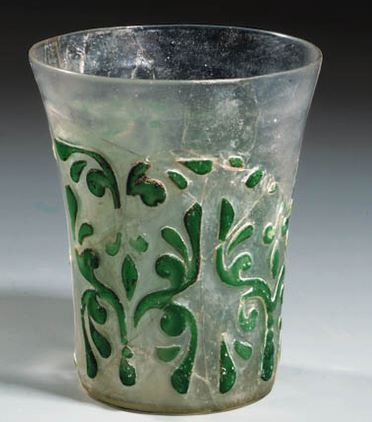

Rim Encheres also held an auction in March, selling only 36% of the lots for a total of €248,573. Given the fact that the house is only two years old, expectations differ, but we can already highlight that the objects sold most often within their estimate, which somehow gives a feeling of fairness in the midst of the over-the-top estimates we particularly saw on London’s market. The most successful artefact was a gold sandwich glass cup from 11th c. Iran or Syria, valued €40,000-50,000 and sold for €52,000.

Bonhams also held an auction in Paris in the spring, which brought £229,793. Several lots were described as coming from a royal collection without more details.

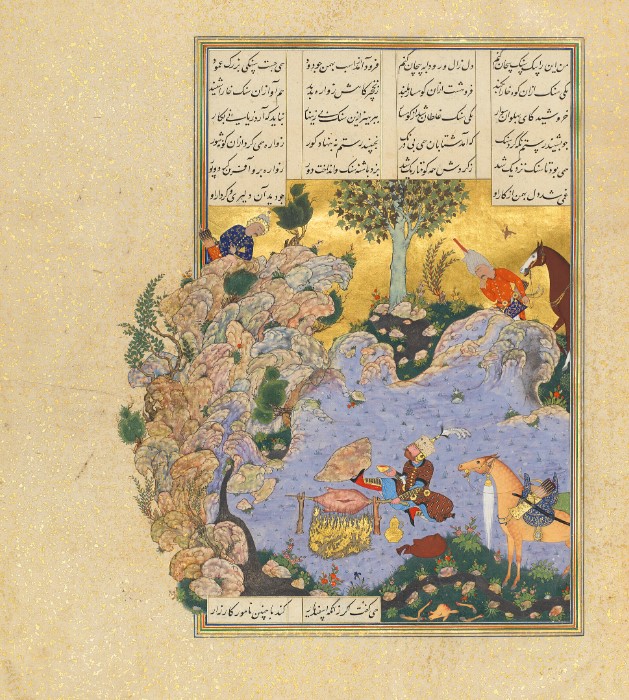

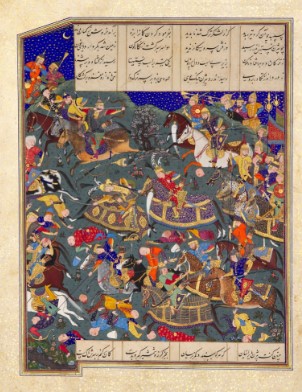

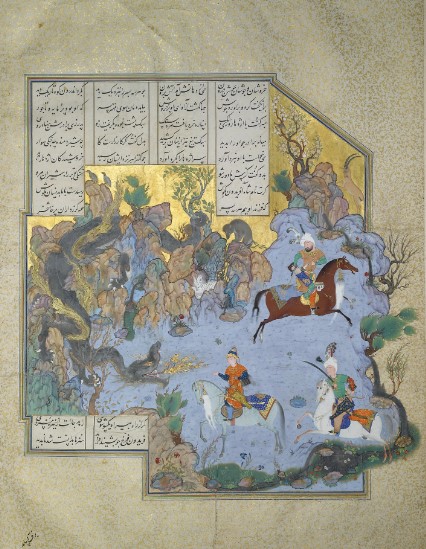

Sotheby’s dominated both Islamic weeks in 2023, and with them the whole market, holding three auctions for a total around £29,643,612, a 59% progression compared to 2022. April saw another folio from Shah Tahmasp Shahnama depicting “Bihzan slaying Nastihan” come on the market, this time a fight scene which was expected to do less than previous folios with less violent paintings, especially the extraordinary depiction of “Rustam recovers Rakhsh from Afrasiyab’s herd” sold in October 2022 for £8,061,700. “Bihzan slaying Nastihan” sold for £4,875,800.

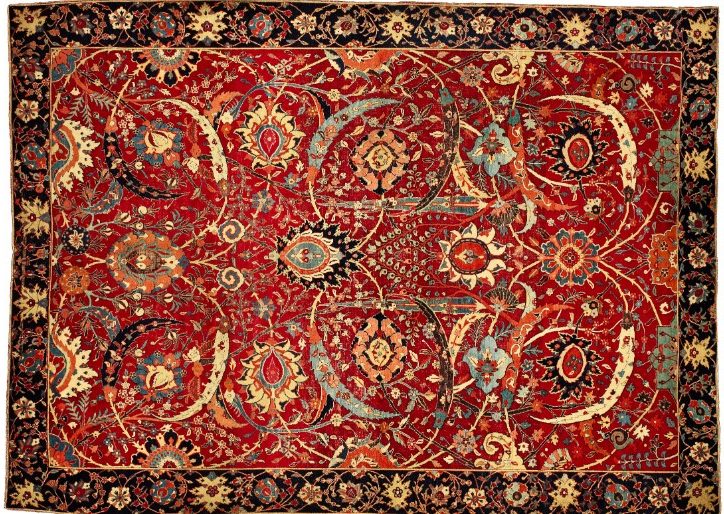

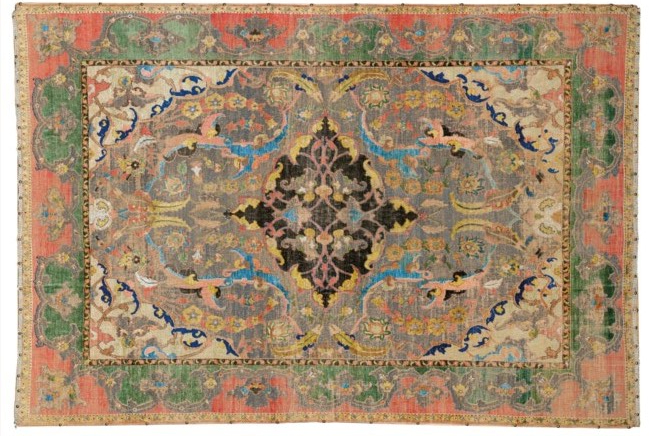

The big surprise was Christie’s overall result, sitting at £17,826,655, a 41% decrease compared to 2022. One must admit that 2022 was a particularly rich year for the house, with the sale of several multimillion lots, including a page from Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama for £4,8 millions in March and a Mughal pashmina carpet for £,5,2 millions in October 2022. In 2023, only two objects passed the million; a gold finial from Tipu Sultan’s throne for £1,8 millions in April, and a rare signed and dated Meccan manuscript of the Futuh al-Haramayn for £.1,2 millions, sold against a very low estimate of £20,000-30,000.

Roseberys surpassed £1 million in April with an auction that included archaeology and a few contemporary pieces. Roseberys’ strategy is quantity over price, with auctions composed of more than 500 lots each and inviting estimates for old and new collectors. This approach has clearly worked for the house this year, with exciting biding battles, especially a dated and signed Mamluk astronomical treatise produced in 697/ 1298 in Egypt or Syria, valued £600-800 for its poor preservation state and sold £182,000.

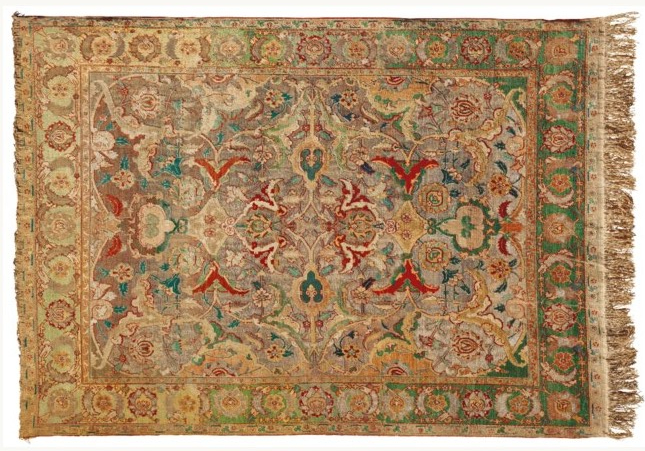

Similarly to Roseberys, Chiswick favoured quantity over price without compromising on quality neither, with catalogues of 300 to 400 lots each time. The other asset of the house for the past few years has been the progressive sale of a single-owner collection, mainly composed of Persian pieces, which overall sold more than 95% of the lots over 6 sales. The top lot in April was a 17th c. Safavid ceramic tile showing the bust of a man holding a blue and white ceramic vase, which sold for £25,000.

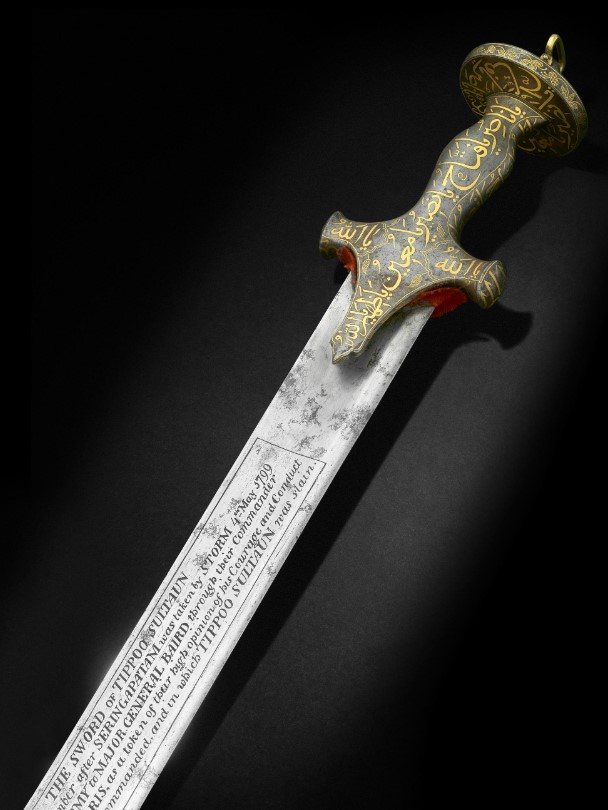

The main surprise of the year was brought by Bonhams, which achieved a total result of £17,826,655 in 2023, a 976% progression from 2022 (this percentage is not a typo). I wrote in November 2022 that Bonhams was not doing too well financially, recording their lowest result in 10 years, but 2023 saw them rise again. In May, records were broken by the sale for £14,080,900 of the bedchamber sword of Tipu Sultan, climbing to the second place of most expensive Islamic art object ever sold at auction.

Also in May, Artcurial held their first auction of the year, which was crowned by the presentation of an Abbasid Qur’an from the end of the 12th century, valued at only €20,000-30,000 and sold without surprise for €406,720.

Like in 2022, Millon arrived in first place of the Parisian market with a overall result of €2,528,631 for two main and two online sales. June auction highlight was also a 12th century Qur’an, this time in Kufic script, sold within its estimate for €150,000.

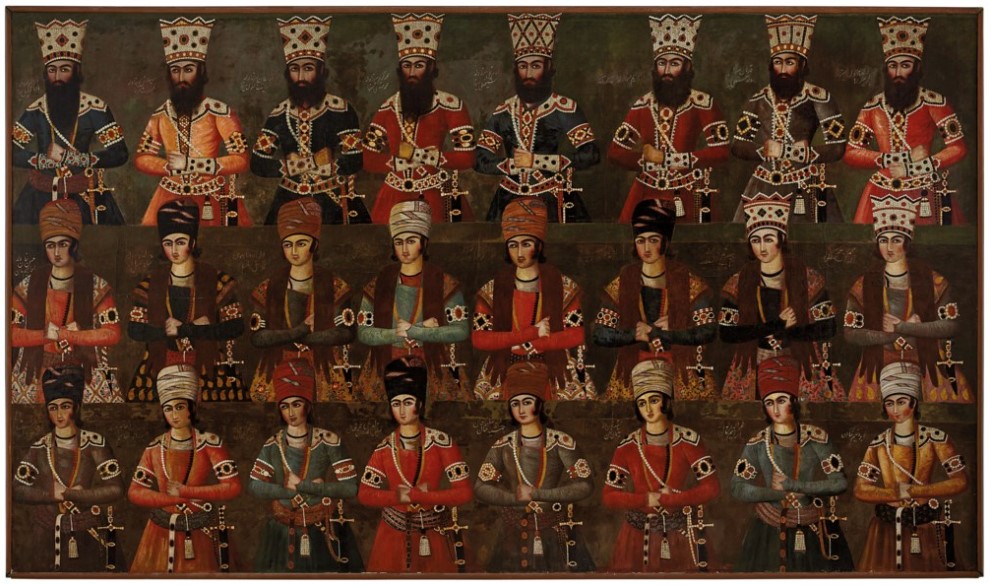

Sotheby’s progression this year is partly due to the Shahnama page sold in April, and partly to the immense success of the sale of Edith and Stuart Carry Welch’s collection in October which made £10,853,253 in total, £ 8,102,600 for Islamic and Indian art only. The second part of the Welch sale was online, the 56 Islamic and Indian lots bringing an additional £127,763. The ‘normal’ October auction included two unsold top lots, a halftone result compared to April but that still made £6,718,554, nearly a million more than Christie’s, which brought £5,766,218. Christie’s also had a single-owner auction next to the ‘normal’ sale, offering a large selection of Indian and Persian paintings from the collection of Toby Falk, renowned Islamic art history scholar who passed away in 1997.

Sidenote: Scholarly and conversation jobs don’t pay that well, at least these days, so I would love to understand how Stuart Cary Welch and Toby Falk managed to constitute collections as extensive and packed with masterpieces. Let’s not forget S.C. Welch owned a page of Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama, the most expensive manuscript in the world, which sold in 2011 for £7,433,250. In the 70s and 80s, the Islamic art market was not as big as it is now, but even then, both collectors must have spent fortunes buying some of these pieces. There is clearly a secret here I do not possess. If someone knows, please share. End of sidenote.

The biggest success from the Welch collection was the painting of “an Assembly of Village Elders with William Fraser’s munshi and diwan”, beautifully depicted around 1816, valued £150,000-250,000 and sold for £952,500. It had been acquired by Welch in 1980 for an amount I couldn’t retrieve. Toby Falk’s highlight was the painting of “a lesser coucal on a frangipani branch” made in 1777 for Elijah Impey, valued £80,000-120,000, sold for £504,000.

The Islamic week was followed in November by Bonhams eventful sale of the so-called Harvard world map, a Mecca-centred World Map made in Safavid Persia in the 17th century, which got its nickname due to the fact it was on long term loan to the Harvard Art Museums until 2014. The lot was first withdraw from the sale, then reintegrated, and finally sold for £1,863,400, against an estimate of £1,500,000-2,000,000.

Artcurial November auction was not nearly as profitable as April’s, reaching only €474,797 thanks to the presentation of a 14th century Mamluk domed casket sold for €183,680. Overall Artcurial arrives second on the Parisian market with a total result of €1,478,955, a 32% progression since 2022 (excluding archaeology that is managed by a different expert). This result is due to a clever choice to offer smaller, carefully curated catalogues centred on few unpublished pieces with stellar provenance and great catalogue work. To be noted that Pingannaud-David expertise is also making moves outside of Artcurial, namely with Gros & Delettrez, a house mainly known for their orientalist painting sales. For the very last auction of the year, they presented a small catalogue of 34 lots centred on an extraordinary “Damascus room”, unpublished and in great condition. At the time of writing, the results were yet to be published, but we can already note that the main part of the room sold for €340,000 hammer.

Rim Encheres held a small but successful auction in December, selling 92% of the lots for a total of €128,583, including an Ottoman kilij sabre with pommel and sheath entirely covered in red coral and turquoise, sold for €22,100.

Finally, Millon made around €1,026,244.83 with their second main auction, which consisted in parts in a large private collection constituted in the 19th century and preserved in an extraordinary apartment in Bordeaux. You can see some of the amazing setting in a presentation video by the expert Anne-Sophie Joncoux-Pilorget. The auction itself surprised everybody when a 14th c. Mamluk silver-inlaid brass candlestick valued €20,000-40,000 sold for €180,000.

My predictions for 2024

This is the tricky part of this article, and my predictions might end up completely off tracks. The Islamic and Indian art market is difficult to predict due to its very diverse nature. Aside from archaeology, no other market covers geographic and chronological ranges as large, not to mention the whole panel of artistic media, from engraved animal bones to entire architectures. What comes on the market also depends on what experts are able to source and who is willing to sell, so all this to say that there are a lot of unknowns from one season to another. That being said, looking at 2023, we can go into 2024 with a few expectations.

Three pages of Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama were sold since 2022, and though none got offered in the autumn Islamic week, it wouldn’t be surprising to see more appear on the market this year given the continuous success of previous pages. That being said, collectors might decide to hold off selling their piece for a few years to create an event as big as the presentation of “Rustam kicking the boulder” by Christie’s in April 2022.

Given the results achieved in 2023 by all kind of Tipu Sultan’s memorabilia, we would probably be right to expect more to come on the market in 2024. The sale of Tipu Sultan’s bedchamber sword by Bonhams aside, Christie’s also made the top 22 in April by selling a gold finial from Tipu’s Throne for £1,855,000, and Sotheby’s sold a sword with ruby eyes for £1,197,500. Christie’s sold another sword for £100,800 in October, while two other remained unsold. Bonhams sold a gilt-copper hilted steel sword from Tipu’s armoury in November for £89,300, as well as various artefacts such as a engraving and newspapers. Autumn auctions has shown that buyers will not jump blindly on every object marked Tipu Sultan, even when the provenance is solid, and my assumption is that the price of the bedchamber sword will remain extraordinary for the years to come, thanks to a perfect storm of long and prestigious provenance and clever marketing.

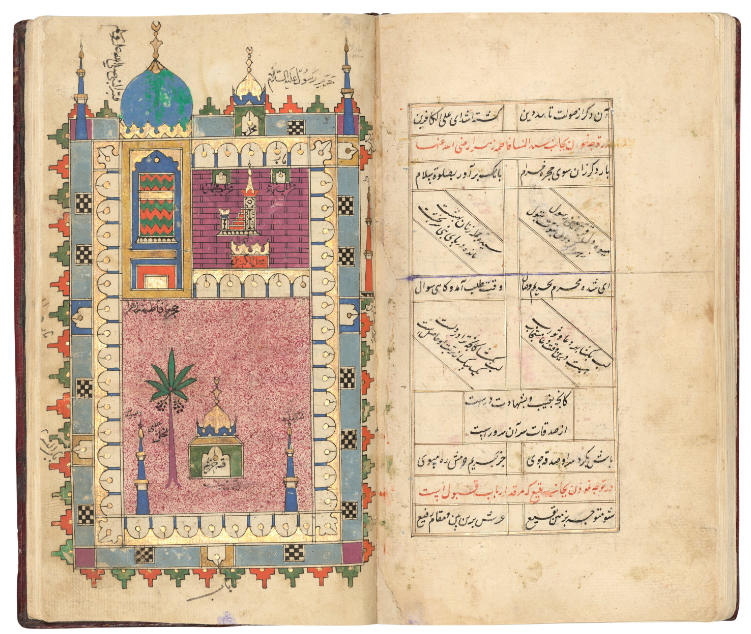

It seems that a small but highly lucrative niche is getting carved around rare religious and history manuscripts. In April, Sotheby’s achieved high results on two unexpected items, a Hajj map made in 1329/ 1911, valued £10,000-15,000 and sold £40,640, and a copy of the Kitab akhbar Makkah dated 77/ 1374 (history of Mecca), valued £200,000-300,000, sold £762,000. In June, the trend continued with the Abbasid Qur’an sold by Artcurial for €406,720, as well a Mamluk copy of the 7th volume of the Kitab al-tamhid of Abd al-Barr, dated 695/ 1296, sold in the same auction for €59,040 against an estimate of €8,000-12,000. The volume was remarkable for many reasons, including its known calligrapher, its preservation and the historical notes it contains. In October, Christie’s sold a large 18th c. Kashmiri prayer book for an astonishing £108,360 against a valuation of £15,000-25,000, and the aforementioned copy of the Futuh al-Haramayn made in Mecca in 1003/ 1595 for £1,250,000. I’ll be interesting to see where this goes.

Finally, medieval metalworks might be making a come-back, maybe. I am never confident when it comes to medieval metalworks and ceramics, buyer’s appeal for both media being quite unpredictable, but the recent results might be the beginning of something. In April, Sotheby’s sold a 12th c. Khurasan feline-form incense burner for £215,900, more than twice its high estimate (£70,000-90,000), Christie’s sold another one the next day for £126,000 (est. £50,000-70,000), as well as an Anatolian Siirt silver-inlaid bronze candlestick for £107,100 (est. £40,000-60,000). Chiswick best results in October were two 12th or 13th c. ewers, a silver-inlaid bronze one for £11,250 and a copper-inlaid brass one for £9,375. In Paris, Artcurial sold the aforementioned Mamluk domed round casket made in the first half of the 14th c. for more than twice its low estimate, and Millon sold their Mamluk candlestick for 9 times its low estimate. Objectively, I was not expecting this kind of results, and I’m intrigued to see what the new year will bring for mediaeval metalworks. See you in April for more!