The effect of the Pandemic on the London Islamic week of Spring 2021

The year 2020 has been challenging for the world and everybody on the planet has felt the impact on the pandemic. Not being out of the woods yet, the beginning of this year seems more hopeful with the promise of a vaccine in most countries, but we’ll more likely see long-term effects of this crisis, starting with the London Islamic week of Spring 2021.

For the Islamic arts market, and the art market in general, 2020 has forced a rapid shift, proving the capability of auction houses to adapt, but not without consequences.

All prices below include premium.

A rapid shift to avoid the worst

From a purely financial perspective, the worst was avoided. For pre-modern Islamic and Indian arts, Sotheby’s took the biggest hit, achieving overall £10,526,614, a 31.6% decrease compared to last year. Christie’s maintained its base revenue with £21,927,125, a 0.41% decrease from 2019, but excluding the exceptional sale (as in “one time event”) of the al-Thani collection, held in New York in July 2019 and that made $109,031,875.

Bonhams sustained a 32% growth by maintaining its 4 annual sales, two live and two online, while Chiswick auctions registered a 5.75% decrease while adding additional online auctions.

In France, Millon et Associés also endured the pandemic with a 37.2% decrease in revenue, also due to the fact that 2019 was an exceptionally good year for this house that managed to sell a page of the Padshanama.

Sotheby’s heavy decline can be attributed to two things. First, a disappointing spring auction where most of the star items didn’t sell, such as the blue and black Kashan ewer from the Edward Binney III collection. Overall the sale made £3.6 millions, Sotheby’s London lower result since October 2017. Secondly, the sale of artefacts from the L.A. Mayer Museum in Jerusalem, aborted due to the controversy surrounding deaccessionning, was a blow for the house that was already behind his main competitor.

Travel restrictions, forced closure of non-essential businesses and the overall insecurity about the immediate future could have turned most buyers away, but the move to online auctions, already initiated in the previous years, allowed a smooth transition. Online catalogues, online bidding and 360° exhibition tours are already a tool for major houses, but the pandemic has accelerated the process. We can expect to see printed catalogues disappear completely in the next few years, Christie’s having already announced its plan to decrease by half the number of catalogues sent around the world.1

A Cloudy Present: London Islamic week of Spring 2021

The biggest London auction houses, Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams have just published their catalogue and their content seem to reflect both the effects of the pandemic and the increasing challenges of the Islamic arts market. Firstly, the catalogues are a lot smaller than usual: 141 lots for Bonhams presented on the 30th March, 183 lots including 45 carpets for Sotheby’s on the 31st March and 157 lots including 57 carpets at Christie’s on the 1st April. In comparison, Christie’s had 205 lots in 2020 and 302 in 2019. The pandemic has made it more difficult for experts to travel and source objects, but more generally, it is getting harder to source never sold before items.

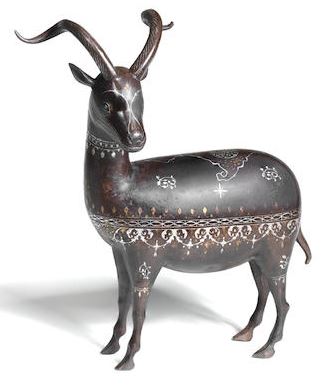

That being said, both Christie’s and Sotheby’s have managed to source unpublished star lots. The 13th century Khorassan basin with silver-inlaid astrological figures is nothing less but extraordinary. The silver decoration is mostly intact, which is rare given the fragility of silver incrustations, while the size (50 cm diameter) and the quality of the figurative decor make the high valuation, £1.000.000-1.500.000, completely justified. For the first time since 2010, Christie’s most expensive lot is a 19th century Qajar painting2, known to have been part of the collection of late artist Frederic Clay Bartlett (1873-1953). The massive group portrait, valued £1.000.000-1.500.000, is described in extensive details by Dr Layla S Diba, great scholar of Qajar Iran. The painting is presented as a “rediscovery”, but it was never lost, it was part of the permanent and exposed collections of Bonnet House Museum and Gardens. About its sale, Patrick Shavloske, CEO, commented:

But the time has come for the Qajar painting to move to a new home that is better positioned to give the artwork the care and honour it so richly deserves. Proceeds from the Qajar painting sale will be used by the museum to conserve its paintings by Frederic Clay Bartlett and Evelyn Fortune Bartlett as well as the historic Bonnet House itself, also an artful creation of the Bartletts.3

Museums deaccessionning part of their collections to compensate the lost of revenues caused by the pandemic have sparked a large debate, and though the sale of L.A. Mayer Museum at Sotheby’s ultimately failed, this auction is not getting the same traction, most likely because it is limited to one artefact.

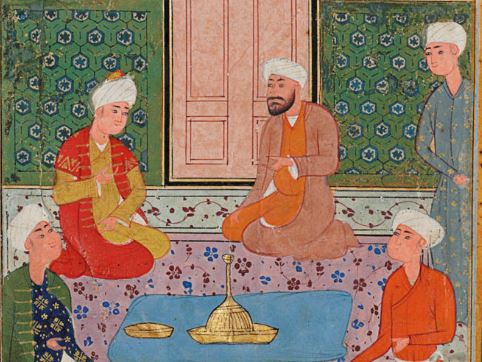

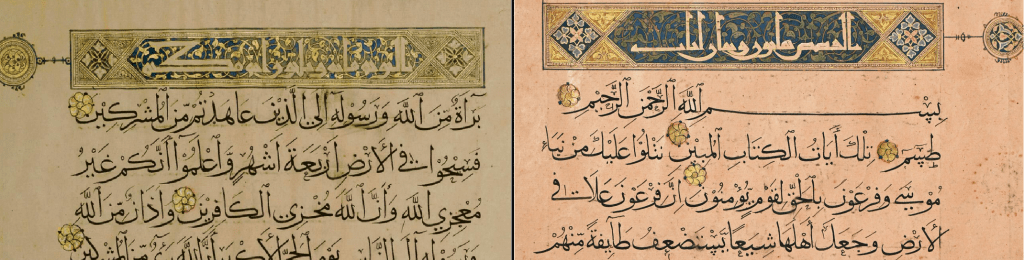

Both Sotheby’s and Christie’s have managed to source interesting manuscripts. Christie’s is presenting a Qur’an with a colophon bearing the name of the famous 13th century calligrapher Yaqut al-Musta’simi, valued £300.000-500.000. The manuscript was illuminated in 17th century Safavid Iran, but the writing looks genuine to a non-specialist of Ilkhanid calligraphy such as myself. We can regret the fact that Christie’s didn’t get the opinion, nor even quote Dr Nourane Ben Azzouna, specialist of Yaqut al-Musta’simi, to confirm if the manuscript is genuine.4 A genuine manuscript signed by one of the greatest masters of calligraphy is an event that would have required further investigations.

A surprising view in Christie’s catalogue is the page wrongly attributed to the St Petersburg Muraqqa’, sold at Sotheby’s in 2018 for £25.000 and discussed on this blog. This time, the page is valued at £7.000-10.000, a huge drop from the initial sale price.

Sotheby’s is presenting a very interesting Qur’an dated 920/ 1514, signed by the calligrapher and dedicated to the Chief of Justice of Jerusalem and Nablus, only 2 years before the conquest of Jerusalem by the Ottoman armies. The arts of the book from the extreme end of the Mamluk dynasty have not been studied in much details yet, so this complete manuscript constitutes an interesting testimony of the period.

Some lots, however, clearly reflect the difficulties that both Sotheby’s and Christie’s had constituting exciting catalogues. For instance, Christie’s presents a “page from the Nasir al-din Shah album“ valued £3.000-5.000. Though this page might be attached to an album produced for the sovereign of the Qajar dynasty, Nasir al-Din around 1888, the page is not from the Nasir al-din Shah album, very famous muraqqa’ initially gathered in Mughal India and passed to Iran after Delhi sac by the army of the Afshar king Nasir al-din Shah in 1747. Words matter, though I do not think buyers will be duped.

Same goes with a Mamluk Qur’an page on pink paper offered by Sotheby’s for £6.000-8.000. The page is dated in the catalogue circa 728/ 1327 on the basis of a different page sold in 2008, also undated but previously published by the art dealer Philip C Duschnes as originating from a Qur’an written by Ahmad b. ‘Abdullah b. al-Mansur Hashemi al-‘Abbasi, completed 7 Sha’ban 728. This convoluted datation is problematic, especially given that I am not completely convinced the page from 2008 comes from the same manuscript as the two pages from 2011 and 2021. My doubts are based on the different quality level of the kufic script in the headers and some details in the thuluth script. Beside the fact that the colophon remains unpublished to this day, the datation of the page can be questioned on the basis of the illumination style, closer to the productions from the second half of the 14th century than the late 1320’s.4

Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonhams catalogues contain a majority of later artefacts, mainly 18th and 19th centuries, which reflect the difficulties the houses have encountered sourcing Medieval and Pre-Modern objects. This might be why some attributions to the Safavid era seem a bit far-fetched.

For £100.000-150.000, Christie’s is offering an album page showing the rest on the flight into Egypt, given to the famous Safavid painting Muhammad Zaman and dated 1076/ 1665-66. I have several problems with this page beside the commonplace of the inscription, ya saheb al-Zaman, often linked to the painter without much afterthoughts, so here come the bullet points:

- Though Biblical themes and copies from European prints have been a constant in Muhammad Zaman career, the style of this particular painting doesn’t fit the painter’s, it lacks the roundness of his forms and the volumes created with strong shades.

- The painting is on vellum, which is a highly singular for Muhammad Zaman and Safavid painters in general (though they have experienced with various media).

- The painting is signed but unfinished, which is unprecedented in Muhammad Zaman catalogue

- The date 1076/1665-66 seems to be too early in the artist’s career. Though Muhammad Zaman biography is still open to debate, the core of his work is dated from the 1670s to 1690s, with a seemingly confirmed date of death in 1700.

Despite a smaller catalogue, Bonham’s has managed to remain coherent with their usual focus on later Indian art, particularly Punjabi and Sikh. Their star lot is a 19th century portrait of Raja Lal Singh by the Austrian painter Augustus Theodor Schoefft, valued £150.000-250.000. Among the most prestigious artefacts feature a gorgeous Chand-Tikka from the collection of Maharani Jindan Kaur (1817-63) valued £90.000-120.000 and a large manuscript of Janamsakhi from late 18th century Punjab, given for £25.000-35.000.

The main object of curiosity in Bonham’s catalogue is an oil on canvas full-length portrait of an “African soldier“, given to Safavid Iran circa 1680-90, valued £100.000-150.000. The notice has been written by Dr Eleanor Sims, scholar of Safavid painting and who has published on a series of 21 full-length portraits on canvas she dates from the 1680s.6 I have personally never been convinced these 21 paintings were produced in the 17th century under Safavid rulers, I think they were made later, maybe during the 18th century during the reigns of Zand or Afshar dynasties. This is an unpopular opinion and no doubt some will disagree, but given what we know about painting production, artistic fashion and stylistic evolution of Pre-Modern Persian painting (16th-19th c. roughly), there is no good explanation for this production of full scale oil paintings, coming from nowhere and disappearing as it came before becoming highly popular under the Qajar dynasty in the 19th century.

Regarding the “African soldier”, I am obviously not convinced neither. Despite the accurate depiction of weapons described by Dr Sims, I do not believe this man to be a soldier, as the garb does not fit the representation of actual Safavid soldiers, and I do not believe he is from the 17th century as evoked above.

Dr Sims worked with Christie’s in 2019 to attribute the paintings of a 15th century manuscript to the famous painter Behzad, in a demonstration that convinced no one since the manuscript remained unsold. Given this track record and the questions surrounding this portrait, it will be particularly interesting to see what price it will achieve.

This Islamic week definitely carries the weight of the pandemic, and though the three catalogues also contain some interesting items, we can wonder if the pressure for spectacular lots haven’t forced the experts to cut some corners. Travel restrictions in 2020 haven’t particularly blocked buyers, but the quality of the catalogues might.

- “Le bilan 2020 du marché de l’art”, L’objet d’Art, 575 (Feb 2021), p. 76.

- Last time was the Portrait of a Nobleman signed Isma’il Jalayir, estimated £500.000-800.000 and sold £601.250. Christie’s 13.04.2010, lot 150.

- “A rediscovered Qajar painting from Bonnet House Museum Gardens leads Christie’s auction”, artdaily

- She has published many times on the topic of attributions to this calligrapher. See her latest book, Aux origines du classissisme. Calligraphes et bibliophiles au temps des dynasties mongoles (Brill, 2018), pp. 48-132 in particular.

- Thank you to Dr Adeline Laclau for her expertise on this page.

- Eleanor Sims, “Five Seventeenth-Century Persian Oil Paintings”, Persian and Mughal Art, London: 1976, pp. 223-32; “The “Exotic” Image: Oil-Painting in Iran in the Later 17th and the Early 18th Centuries”, in The Phenomenon of ‘Foreign’ in Oriental Art, Wiesbaden: 2006, pp. 135-40; “Six Seventeenth-century Oil Paintings from Safavid Persia”, in God is Beautiful and Loves Beauty: The Object in Islamic Art and Culture, New Haven: 2013, pp. 343, 346-47.