Welcome back dear reader of this humble blog, I hope you had a good summer! Autumn is already here, and with that, London Islamic week is arriving quickly.

A short disclaimer before we start: this blog article is coming out very late, is shorter and a rougher than planned. I caught a bad cold last week and have been completely unable to get any work done for several days. Instead of completely abandoning the writing, I decided to publish an “as is” version. Hopefully this will still be informative, and I will review the results later on.

This season, 8 auctions will be held between the Wednesday 25th and the Tuesday 31st October, as follow:

- Sotheby’s 18th to 27th October, online: “The Edith & Stuart Cary Welch Collection”, 260 lots

- Sotheby’s 25th October, AM: “The Edith & Stuart Cary Welch Collection”, 130 lots

- Sotheby’s 25th October, PM: “Art of the Islamic World & India”, 157 lots

- Christie’s 26th October, “Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds including Rugs and Carpets”, 215 lots

- Christie’s 27th October, “An Eye Enchanted: Indian Paintings from the Collection of Toby Falk”, 152 lots

- Roseberys 30th October: “Antiquities, Islamic & Indian Arts”, 542 lots (including 67 antiquities and 21 contemporary)

- Chiswick 31st October, AM: “Property of a European Collector, part VI”, 84 lots

- Chiswick 31st October, PM: “Islamic & Indian arts”, 354 lots

Some will have noticed I have left Plakas auctions out of this review, despite them having a sale scheduled on the 24th. Plakas have no named expert, and the authenticity a number of objects presented in the catalogue is highly questionable. They are also plagiarising the work of known experts, namely the complete description of a near complete late 12th c. Abbasid Qur’an sold at Artcurial earlier this year. Plakas is selling one page of this manuscript and just copied and pasted Artcurial text, including the provenance. This is wrong on many levels and actions are being taken as I write, so I will not discuss this further.[efn_note]Thank you to the Artcurial team for confirming this information, including the fact that the provenance of the page sold at Plakas is not the same as the rest of the manuscript.[/efn_note]

Because Bonhams delayed their previous auction, they will hold their next one on the 14th November and their online sale from the 11th till the 15th November. Separating themselves from their competitors has worked quite well, achieving the second-highest result since 2010 with the sale of Tipu Sultan’s bedchamber sword. If you want to know more about it, check the Top 20 of the most expensive Islamic art objects ever sold, part 1 and part 2.

Lastly, and before jumping in the auctions, let’s note that this Islamic week is Beatrice Campi’s last at Chiswick auctions. Beatrice built the Islamic and Indian department from scratch 6 years ago and has positioned the house as a solid player on the London market for affordable art. The future is now very uncertain for the department, as finding a replacement for Beatrice is proving to be a struggle, but I wish to congratulate Beatrice on 6 beautiful years, and I cannot wait to see what she’ll do next.

In the same vain, Behnaz Atighi Moghaddam, head of sales at Christie’s, has now gone on personal leave, and corridor conversations are questioning the future structure of the Islamic art department.

Beautiful Objects and Hefty Prices

Sotheby’s opens this Islamic week with 120 lots, on top of which is an Abbasid astrolabe, maybe made in Baghdad circa 900, valued at £1,500,000-2,500,000. The artefact comes with an Egyptian and European provenance and a well written notice. I have little opinion when it comes to astrolabes but given the high estimate, I am quite interested to follow the sale. This is most likely a museum piece which might interest institutions of the Gulf, so we might see some action.

Christie’s biggest entry is a 16th century Safavid ‘Palmette and Bird’ carpet, valued at £2,000,000-3,000,000, from the collection of baron Edmond de Rothschild, previously published and presented several time at auctions. It was sold most recently at Sotheby’s New York in 2013 for $1,930,500, so 10 years later, this carpet might break records.

Chiswick and Roseberys thankfully maintain their prices. Roseberys highest valued object is a Still Life by the Indian artist F.N. Souza dated 1986, valued £30,000-50,000. Roseberys has slowly but surely been including more contemporary pieces in their Islamic and Indian art catalogues, but having a contemporary painting as the top lot is unusual, so I am curious to see what repercussion this might have on future auctions. The second most expensive lot is the full book collection of Pr JM Rogers, Islamic art historian and pioneer, who passed away in 2002. This includes around 900 books, valued at £15,000-20,000, which will most likely be bought by a museum or a library. Two uncommon top lots!

Chiswick went with a more traditional route by presenting a large Mamluk brass candlestick for £15,000-20,000 in their afternoon auction. According to the description, it was recently bought in France, but I couldn’t retrieve from where (I didn’t look too hard to be fair). The blazon engraved on the body indicates it was produced in the second half of the 15th century, but without further precision.[efn_note]According to M. Meinecke (1972), quoted by Julia Gonnella on Museum with no Frontiers, 47 amirs of the late Burji period used this particular blazon.[/efn_note] Chiswick is also offering the last part of the single-owner collection they have been selling for the past three years, the star lot being a 12th/13th Persian coper-inlaid brass ewer valued at £2,000-3,000. The auction of the five previous parts all did really well, including several white-gloves sales, and we can expect similar results this time around. What an amazing collection!

Additionally, we can only regret the lack of provenance on many lots from all four auction houses. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, at this point in time, undisclosed provenance in catalogue should not an acceptable practice. Auction houses obviously do their due diligence, but the opacity of the market has real consequences. We know artefacts and manuscripts are being looted or stolen from small, unpublished collections to be sold through port-francs, this is nothing new, and the only way to combat this is by being crystal-clear on provenance. Christie’s is selling Persian and Kashmiri manuscripts with no provenance line (lot 90 and 91), and an Eastern Kufic Qur’an section from 11th/12th c. Persia with, for provenance, “By repute Private Collection, London, since circa 1990”. How was this even green-lit? In the same fashion, Sotheby’s is offering a beautiful 15th c. Central Asian silk robe, again we no provenance. Stay tuned for more discussion on provenance on the ART Informant podcast.

Building on Success

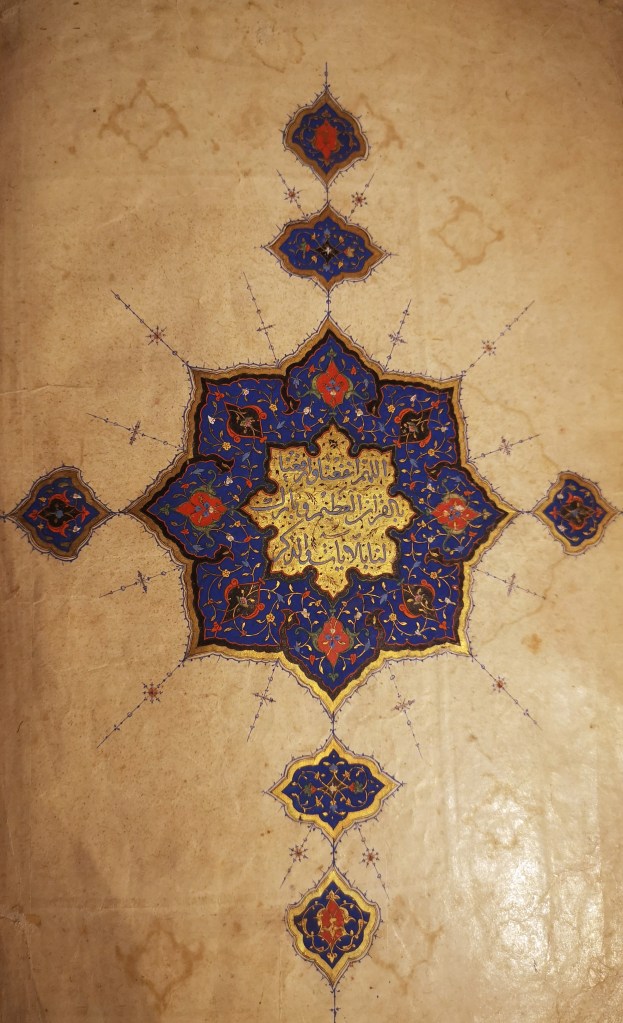

This season feels like a summary of the biggest success in London and Paris these past years. Sotheby’s second highest lot is a 10th century illuminated Qur’an of 247 leaves, including some replaced in the early 20th c., valued at £800,000-1,200,000. The manuscript is extraordinary, described in the catalogue as the earliest surviving Qur’an written in gold on paper, but unfortunately it comes with no provenance. Its presentation in the auction comes after the successful sale of a late 12th c. Abbasid Qur’an at Artcurial, Paris, in May this year, which achieved €406,720 (with premium). Christie’s also builds on that success with an Eastern Kufic section of 42ff from late 11th c. Persia, given at £80,000-120,000.

Unsurprisingly, we are seeing lots of historical swords in Sotheby’s and Christie’s catalogues. This comes after the record-breaking sale of Tipu Sultan’s bedchamber sword, sold earlier this year at Bonhams for £14,080,900, and which is today the 2nd most expensive piece of Islamic art ever sold (but you already knew that since you have read my Top22 blogs). Christie’s fully capitalises on that success with their second highest lot, a sword and scabbard from the personal armoury of Tipu Sultan, dated 1224 H./ 1796-97, valued £1,500,000-2,000,000 (same as Bonhams sword). The provenance is impressive: after Tipu Sultan’s demise, the blade went directly to Charles, 1st Marquess and 2nd Earl Cornwallis (d. 1805) and remained in the family until the cost of living crisis hit the UK and they couldn’t afford heating their castle. Joking aside, this sword is objectively more beautiful than the one sold at Bonhams, with a gold-inlaid hilt in the form of a tiger head, which makes the estimate almost conservative. Two other swords and a mustketoon from Tipu Sultan’s collection are also offered for more affordable ranges (lots 101-103), while Sotheby’s presents one gold-overlaid katar dagger with tiger stripe motifs for £60,000-80,000, attributed to Mysore with the mention of Tipu Sultan in the catalogue entry. The craze for Tipu Sultan lives.

Sotheby’s also offers a composite sword, the blade, most likely 16th century Safavid, bears an dedication to Süleyman the Magnificent (r.1520-66), while the marine-ivory hilt is most likely 18th century. Valued at £100,000-150,000, the historical name might attract buyers, in the same fashion as Awrangzeb’s sword “the army conquest” sold in the previous Islamic week for roughly 5 times its estimate.

For the previous Islamic week, I wrote that the high-end auction houses, particularly Sotheby’s, were expanding their range to objects generally sold on the Parisian art market, or by more affordable houses such as Roseberys and Chiswick. The operation was a success for Sotheby’s, prices achieving surprising heights. To be fair, estimates were high to begin with, with, for instance, a 19th c. Sub-Saharan Qur’an offered for £8,000-12,000, sold £31,750, or an Algerian wooden Arabic practice board valued £3,000-5,000, sold £20,320. Sotheby’s continues their expansion this season with manuscripts from East and West Africa, Dagestan, as well as wooden boards and printed hajj certificates that would normally be considered more as ethnographic curiosities than luxury art pieces. Some of the prices are particularly high. We can, for instance, question the estimate of An illuminated Qur’an from 17th century Algeria, valued £50,000-70,000. While the manuscript is of undoubtable quality and dated volumes from this time and region are rare, North African premodern production has never been a best seller on the London market. These manuscripts are usually favoured by the Parisian market which has more historical ties with the region. This strategy makes sense for Sotheby’s, but it might be detrimental to the Parisian market on the short and long term, we’ll have to wait and see.

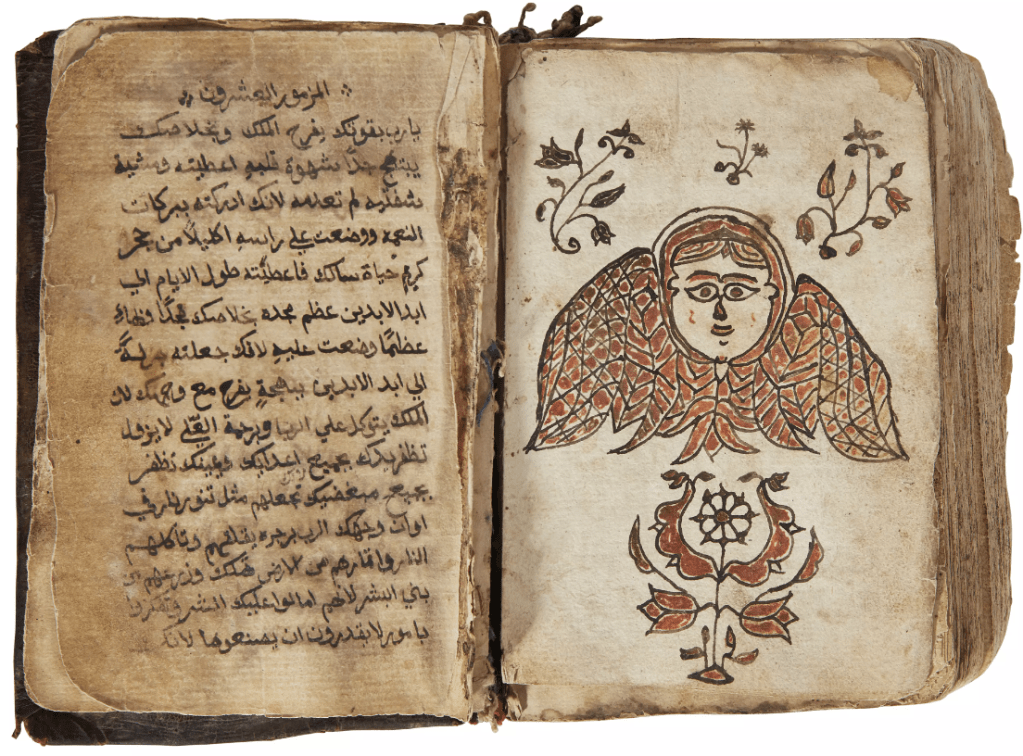

The expansion of the field is once again demonstrated by Roseberys catalogue, which has arguably the most diverse selection (also the largest). It includes several lithographs and early Iranian prints, as well as sub-Saharan manuscripts, Chinese Qur’an sections, and interesting Christian volumes in Syriac and Arabic, including a partial Old Testament from 18th c. Syria or Egypt, previously sold in Paris by Rim Encheres for €800 and offered here for £1,000-1,500.

India in the spotlight

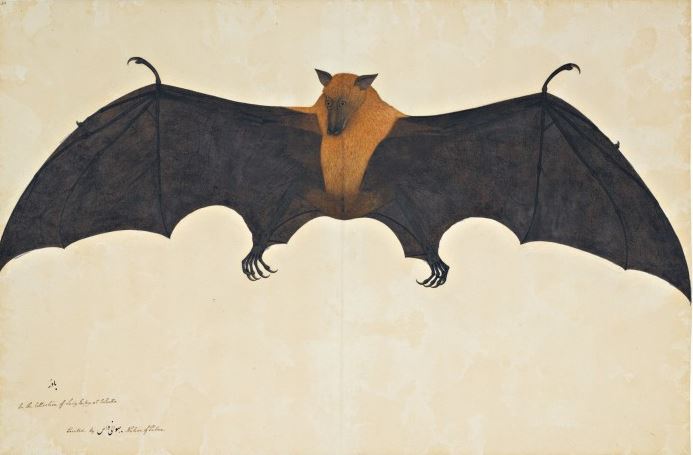

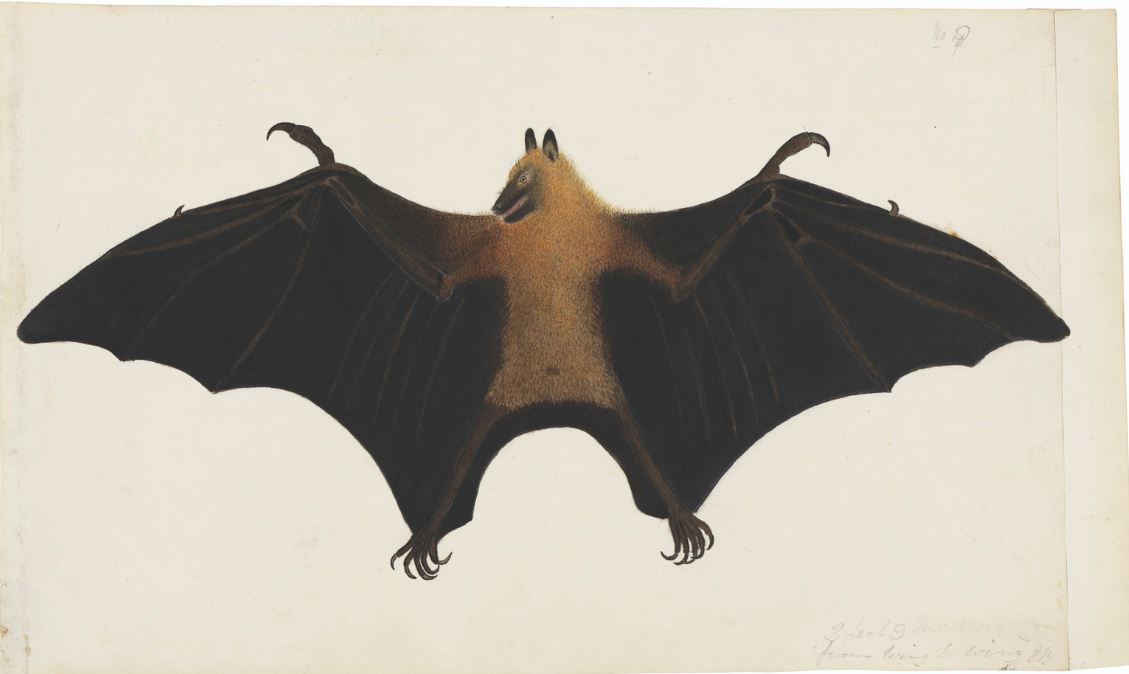

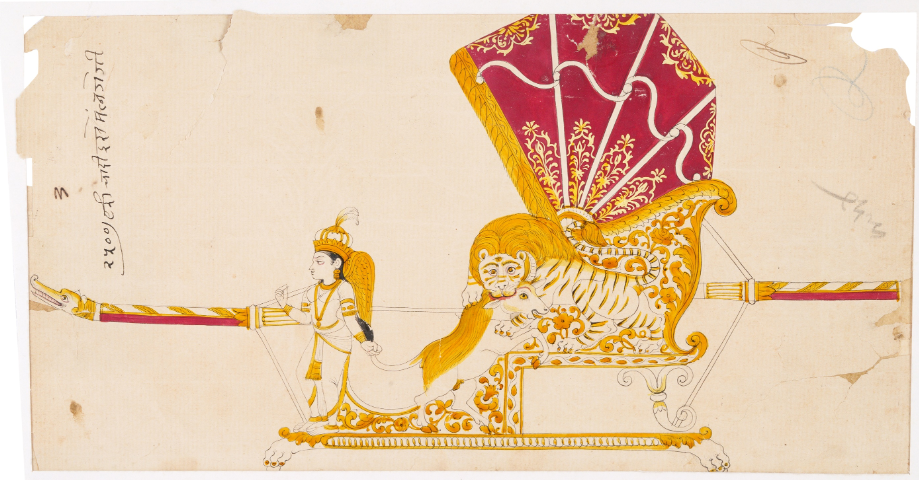

The excitement this season comes from the auction of two major art collections: Edith & Stuart Cary Welch Collection sold by Sotheby’s, and Toby Falk’s collection presented by Christie’s, two important scholars of Indian painting in particular. The Welch collection is sold in two parts, live on the 25th October in the morning, and online from the 18th to the 27th. Sotheby’s made the interesting choice to present the collection has a whole under the Islamic and Indian department instead of splitting between departments, maybe following owner instructions, or to capitalise on the Welch name, known by collectors of Islamic and Indian art but not necessarily by others. The live catalogue includes Chinese, Japanese, and of course Indian artworks, while the online catalogue also includes Persian and European works, with generally lower estimates. Toby Falk’s collection is mainly composed of Indian paintings, with some Persian and Ottoman inclusions here and there. The quality of both collections reflect the impeccable taste of their owners, as well as their access to exclusive material via a network of merchants and collectors it would be interesting to investigate.

Amateurs of Indian arts on lower budgets will particularly appreciate Chiswick afternoon catalogue, which includes almost half on Indian objects, from painting to furniture, jewellery, musical instruments, and other. The prevalence of Indian paintings and objects in Islamic and Indian art auction is nothing new, but it is particularly visible this season and we can question how the market will be able to absorb this influx, especially given the two collector sales come on top of Christie’s and Sotheby’s selection in the main sale catalogues.

My Top 5

I did it for the previous Islamic week after someone asked me and really enjoyed picking 5 items among the treasures offered. This top 5 is just what I would buy if I had the funds regardless of market value or trends. In no particular order:

- Roseberys, lot 500: A picchvai of Krishna fluting among rising lotus flowers, India, mid-20th century. This is the cutest wall-hanging I have ever seen, that is it.

- Sotheby’s, E&SCW Collection, lot 77: Anonymous, “Whose Sleeves? (Tagasode)”, Momoyama-Edo Period, late 16th-early 17th century. Not Islamic but I adore these Japanese painted folding screens. I posted a different one on Instagram last year and I’m excited to see this one!

- Christie’s, lot 50: A Hispano-moresque carved and bone-inlaid cabinet, Spain, 16th/17th c. My love for architectural cabinets will live forever.

- Chiswick, lot 283: A Safavid tile mosaic with yellow peacock, 17th c. Collecting architectural ceramic goes against my principles, however I really love this production of Safavid architectural mosaic, they are so lively and colourful.

- Christie’s, TF collection, lot 9: A peri in a garden, Mughal India, 16th c. The fineness of this depiction is absolutely striking.