I finally have a spare minute to do a part 2 of my Islamic week review, but because it was already three weeks ago, I’m going to share only a few additional thoughts, including on “current affairs”. With these 2-part posts, I’m trying a new, shorter format, that’ll allow me to publish more often, and that is hopefully nice to read. Let me know what you think of it!

To restore or not to restore, here is the (undisclosed) question

Some are going to say that I am on a personal crusade against big auction houses, which is completely false, but we need to talk about restoration practices. They are inherently not a bad thing, but as always, I find the lack of transparency problematic.

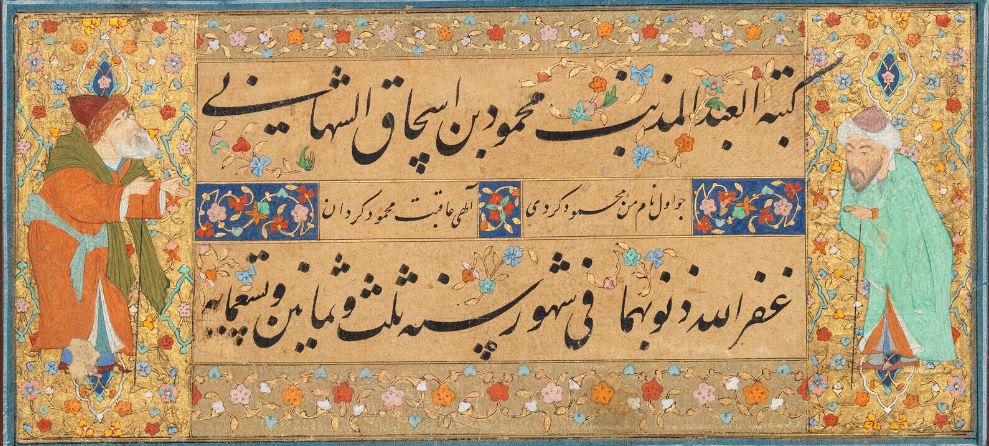

Christie’s sold a painting of a bird signed by the famous Safavid painter Riza ‘Abbasi for £163,800, against an estimate of £100,000-150,000. It was an event to see this painting on the art market again, as the catalogue noted that it was previously sold in 1961 as part of the sale of the Sevadijan collection. Unfortunately, this is not exactly true. As I mentioned in my initial review of the Islamic week, the painting was sold last June in Versailles by Chevau-Leger Encheres for €36,000, against a laughable estimate of €100-150 (talk to specialists, people).1 This auction is not mentioned as part of the provenance in Christie’s auction catalogue. Legally, all bases were covered with the 1961auction, and there was no need to add any information on more recent movements. The problem this omission raises is ethical, and it is misleading to imply that the page had been in a single collection since 1961, when it is, in fact, not the case. The other issue is that between June and October 2022, the painting was restored.

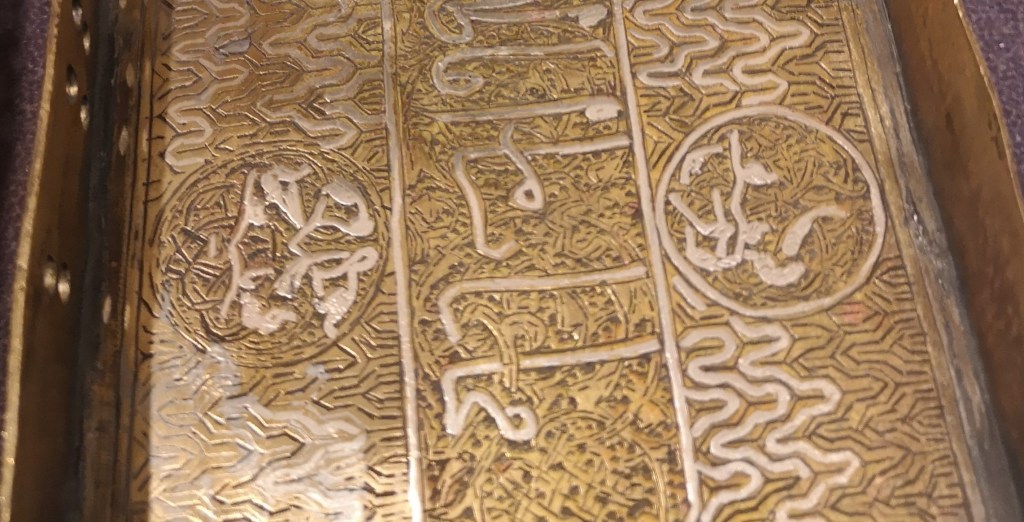

It is a common practice for auction houses to send prestigious pieces such as this one to the restorer. It is particularly common for metalworks, where silver or gold get injected to revive the inlays. Now, I am not against restorations, on the contrary. Restorations are part of the history of individual artworks, and it is great to see a beautiful piece getting back to its former glory. It also makes sense economically, everybody prefers buying pieces in good state rather than completely decrepit. However, restorations should be documented, and in the case of the art market, they should be disclosed. In Western museums, restorations are carefully analysed, weighted and documented. As well, the restoration in case of compensation or loss: “should be detectable by common examination methods.”2 There is no such guideline for auction houses.

The restorations were not mentioned in Christie’s condition report available on the website and laid below, which probably indicates they were conducted by the vendor, as the auction house has an obligation to mention them in condition reports (but not in the catalogue):

This painting is in good and stable condition overall. There are small areas of discoloration on the cream and illuminated background. The gilded areas bear faint discoloration in some areas and some surface craquelure. The pigments used on the bird eye bear light craquelure, as seen from the catalogue image. The multicoloured rock and part of the bird bears small and faint water stains which are only visible upon close inspection. Small area of crease along the left and middle of the painting. The ink of the signature is very slightly flaked, but remains fully legible. The illuminated outer margins include light areas of rubbing and slight discoloration as a result of light exposure. The painting has been pasted down on a blue card as part of the album page it once belonged to.

I will not assume anything regarding Christie’s knowledge, but this shows, once again, the importance of thorough and documented provenance. Collectors should be made aware of potential restorations carried out on their newly acquired piece, as, again, it is part of the history. It is also an element buyers take into account when purchasing a piece, and it is an important piece of information for future restorations. I hope the person or organisation responsible for the repaints on Riza Abbasi’s painting gave all the documentation to the buyer.

The stars shine bright in Paris…

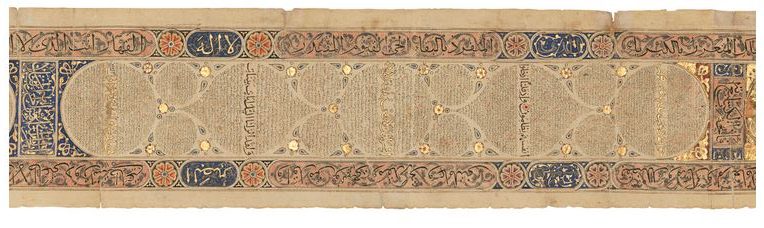

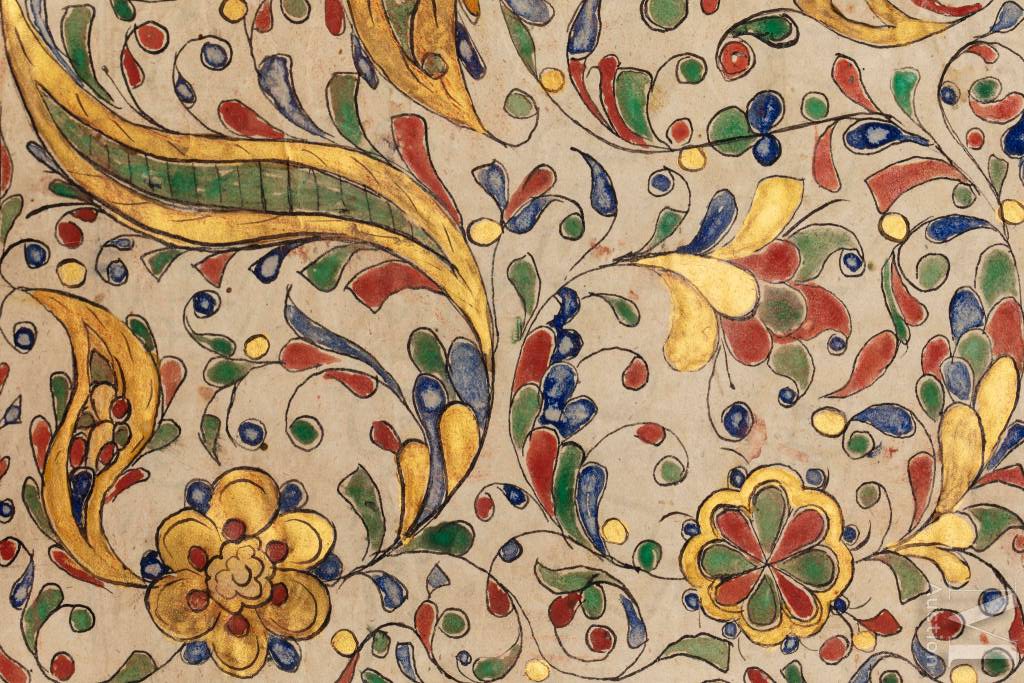

The auction season has started in Paris, and the first results deserve their dramatic title. The auction house Artcurial held their Islamic art auction on the 15th November, under the expertise of Pingannaud-David. They achieved a whooping 813,735€ total (including premium, as for all prices thereafter), an impressive result given that Pingannaud-David expertise was only created a year ago, and that their first auction at Artcurial this summer made only 211,336€. This massive progression is due to a combination of factors, starting with a better selection. Indian painting, which has proven to be quite unpopular in French auctions, was almost completely absent from the catalogue, replaced by a large amount of manuscripts and arms, which are more in favour. Estimates were also scaled down, with very affordable pieces of good quality. Finally, most of the objects had excellent provenances (yes, I’m going to write about provenance again). Objects from R. Froment’s collection were presented, acquired by between the 1950s and 1980s, as well as a selection of manuscripts from the collection of Princess Roxane Qajar (written Kadjar), descendant of Muhammad ‘Ali Shah Qajar (r. 1907-1909). It doesn’t get any better than that. Some of these manuscripts achieved expected high prices, such as the incredibly rare album of illumination motifs from the end of the 19th century, sold 65,600€ against an estimate of 8,000-12,000€. Some prices came as a surprise, such as the 36,736€ paid for a 19th century copy of Khosrow va Shirin value 1,500-2,000€ (dated and signed, admittedly). Among the other success, a rare lustre lantern from 12thor 13th century Ayyubid Syria, sold by Jean Soustiel to R. Froment in 1970, valued 15,000-20,000€ and sold for 111,520€, proving that Medieval ceramics require good provenance to sell well, and an Iznik panel of 3 tiles, proved circa 1570-80, from the same collection, sold at €81,344 against 20,000-30,000€. The craze for Iznik ceramics continues!

…But not on Medieval metalworks

What also continues is the funk in which Medieval metalworks seem to have fallen. Only one was offered, a 12th-13th c. Seljuk silver and copper-inlaid bronze inkwell, which looked nice on pictures (I wasn’t in Paris for the exhibition), but had no provenance other than Sotheby’s 2008. Medieval metalworks didn’t sell in London last month neither, apart at Chiswick which sold everything anyway. Two Egyptian pieces valued at £40,000-60,000 remained unsold at Christie’s, despite the hanging lamp having a provenance line; Sotheby’s kept more than half of their items, etc. I wonder why these artworks fell out of fashion so fast. I mentioned above undisclosed restorations, and of course the question of provenance that is now an important argument, but that’s not all. Rumour has it that many fakes were sold over the years, which would explain the disdain, but I haven’t seen any major public scandal that would have notoriously tainted the medium. This needs further investigation, so I’ll keep my eyes peeled!

The rest of the season will be quite busy: On the 23rd November, Millon will have their third “Orient classique, Trendy, Arty” auction with a large selection at various prices; the 2nd December, Collin du Boccage will present lots from the library of an Orientalist (expertised by Pingannaud-David), Millon will have their main auction on the 13th December, and the 14th December will hold a single-owner numismatic auction, which genuinely excites me. We will have to wait until the beginning of 2023 for Ader (expert Camille Cellier) and Rim Encheres (expert Rim Mezghani), which haven’t announced the dates yet. Stay tuned!

- I am grateful to the person behind the account @completement.marteau for posting first about it in June.

- American Institute for Conservation, Conservation Code of Ethics and Guidelines, art. 23.